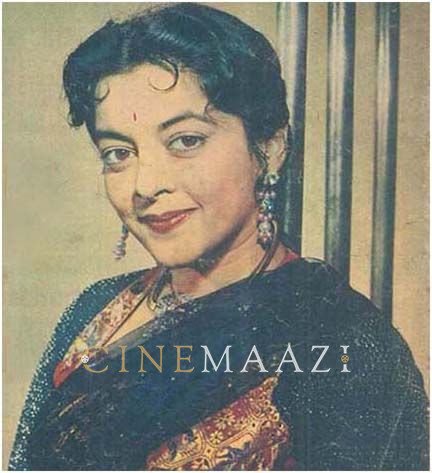

Ismat Chughtai

Subscribe to read full article

This section is for paid subscribers only. Our subscription is only $37/- for one full year.

You get unlimited access to all paid section and features on the website with this subscription.

Not ready for a full subscription?

You can access this article for $2 , and have it saved to your account for one year.

- Born: 21 August 1915 (Badayun, Uttar Pradesh)

- Died: 24 October 1991 (Maharashtra)

- Primary Cinema: Hindi

- Parents: Nusrat Khanam and Mirza Qasim Beg Chughtai

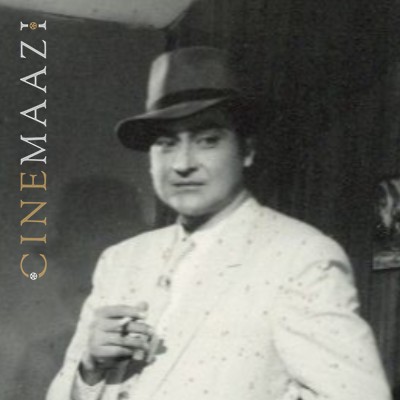

- Spouse: Shaheed Latif

- Children: Seema Sawhny, Sabrina Lateef

Novelist, short story writer, liberal humanist and filmmaker, Ismat Chughtai is one of the most celebrated and prominent Urdu fiction writers of the non-traditional kind. Well known for her critically acclaimed literary works Lihaaf and Tedhi Lakeer, as well as for her work in the well-appreciated films Garm Hava (1974), Arzoo (1950) and Fareb (1953), she is widely regarded as the fourth pillar of modern Urdu fiction along with Saadat Hassan Manto, Rajendra Singh Bedi, and Krishan Chander. Beginning in the 1930s, she wrote extensively on themes that included female sexuality and femininity, middle-class gentility, and class conflict, often from a Marxist perspective. Associated with the Progressive Movement of Urdu, she however chose the internal, social, and emotional exploitation of the subject of her stories instead of the external, social exploitation that was the focus of other communist writers of her time. With a style characterised by literary realism and startling themes, she established herself as a significant voice in the Urdu literature of the 20th century. Focussing on microscopic incidents of human life, she presented them with such dexterity and artistry so as to create a complete and vivid picture of daily life. With her writings mirroring her personality, they radiated sincerity, rebellion, compassion, and innocence. In addition to fame and popularity, she also acquired a measure of notoriety and controversy. In 1976, she was awarded the Padma Shri by the government of India.

Born on 21 August 1915, in Badaun, Uttar Pradesh, to Nusrat Khanam and Mirza Qasim Beg Chughtai, her father was a high-ranking government official. The youngest of nine siblings, all her sisters had been married while she was very young. Growing up in the company of her brothers in her formative years, she played street football, rode horses and climbed trees—things that girls were forbidden to do at the time. She would later describe the influence of her brothers as an important factor which influenced her personality in her formative years. She studied up to the fourth standard in Agra, and till the eighth standard in Aligarh. When her parents expressed their reluctance to permit her higher education, preferring her to train to become a good homemaker, she rebelled. In the face of her threat to run away from home, become a Christian and join a missionary school, her father agreed and she went to Aligarh to continue her education.

It was in Aligarh that she met the staunch liberal, MBBS doctor and women's rights activist Rashid Jahan, who in 1932, together with Sajjad Zaheer and Ahmad Ali, had published a collection of stories titled Angare. On charges of obscenity and mutiny, it had been confiscated by the British. Tremendously influenced by Rashid, as well as by her communist thinking, Chughtai resolved to follow in her footsteps. Conscious of illiteracy being a reason for the shoddy plight of women, she enrolled in an IT college in Lucknow where her subjects were English, Polity, and Economics. It was here that she enjoyed her first taste of freedom, away from the constraints of middle-class Muslim society.

She was just 11 or 12 when she had begun writing stories. In 1939, when her first story Fasadi appeared in the well-known journal Saqi, people believed it to have been penned by her brother, Azeem Beg Chughtai who was a popular writer. It wasn’t long before she created a buzz in literary circles with her stories such as Kafir, Dheet, Khidmatgar, and Bachpan. While the publishing of two collections of short stories titled Kaliyaa.n and Chuntii.n were commendable, trouble was to come with her short story Lihaaf (The Quilt) which appeared in the 1942 issue of a Lahore-based literary journal, Adab-i-Latif. Inspired by the rumoured affair of a begum and her masseuse in Aligarh, the story follows the sexual awakening of Begum Jan following her unhappy marriage with a nawab. Its exploration of the intimate relationship between two women ignited shock and anger in the realm of Urdu literature. Not only did it attract criticism for its suggestion of female homosexuality, the subsequent trial saw Chughtai being summoned by the Lahore high court to defend herself against the charges of “obscenity”. Incidentally, fellow writer and member of the Progressive Writers' Movement Sadat Hassan Manto was also charged with similar allegations for his short-story Bu (Odour) and accompanied Chughtai to Lahore. The trial, which took place in 1945, attracted much media and public attention and brought notoriety to the duo. However, Chughtai garnered support from fellow members of the Progressive Writers' Movement such as Majnun Gorakhpuri and Krishan Chander. Both Chughtai and Manto were exonerated.

Chughtai detested the media coverage of the whole incident, which, she believed also weighted heavily upon her subsequent work. She would say, “[Lihaaf] brought me so much notoriety that I got sick of life. It became the proverbial stick to beat me with and whatever I wrote afterwards got crushed under its weight.” Her other equally good works such as JoDa, Genda, Nanhi Ki Nani, and Bhool-Bhulaiyan were overlooked, as a result.

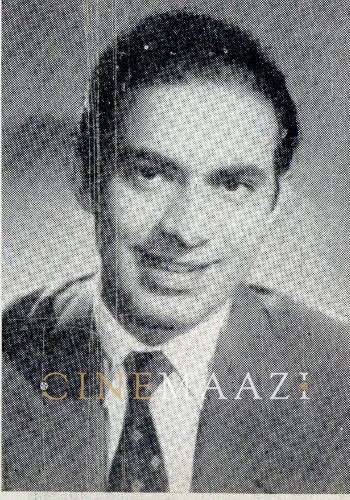

After teaching in different places after she completed her graduation, she moved to Bombay to take up a job as inspector of schools. In Bombay, she also renewed ties with Shaheed Latif, who she had met in Aligarh while he was doing his MA and she worked as the headmistress of a girl’s school; he was now engaged by Bombay Talkies studio to write film dialogues. A stormy romance brewed between them. When Latif proposed to her, she responded, “I am not an ordinary girl. All my life I’ve cut the chains that fettered me, I won’t be able to take up another shackle. Obedience, chastity, and other virtues expected of a woman do not suit me. Lest you repent in the end.” He did not pay heed to her objections and they were wed. Later, reflecting upon her relationship with Latif, she would reveal, “A man can offer love, respect, and even prostrations to a woman, but he can’t give her an equal status; Shahid gave me an equal status.”

Through Latif, she was also introduced to the film industry. As he turned producer, she began to write stories and dialogues for his films such as Ziddi (1948), Aarzoo (1950), and Sone Ki Chidiya (1958). Ziddi, a Latif directorial, saw her pen the tale about the stubbornness of a rich boy to marry the poor girl he loves despite family opposition. The film helped establish its actors Dev Anand, Kamini Kaushal and Pran in Hindi films.

Arzoo, which she penned in 1950, was a romance genre film starring Kamini Kaushal, Dilip Kumar, and Shashikala in a story loosely based on Emily Brontë's 1847 novel Wuthering Heights.

Sone Ki Chidiya, which she penned in 1958, was a romantic drama about an impoverished orphan who is first abused by her extended family, and then exploited after she becomes popular and wealthy. Directed by Latif, it starred Talat Mahmood, Balraj Sahni and Nutan. The film has been described as a significant production for “[chronicling] a heady time in Indian cinema” and showcasing the “grime behind the glamour” of the film industry.

Chughtai's association with film had solidified when she and Latif co-founded the production company Filmina. She is also credited with producing Fareb, Sone Ki Chidiya, and Lala Rukh (1958), a romantic drama directed by Akhtar Siraj and starring Talat Mahmood, Shyama, and Vikram Kapoor.

In 1953, she made her debut as director with Fareb, which she directed along with Latif. The drama film featured Amar, Maya Dass, Kishore Kumar, Shakuntala, and others.

Jawab Ayega, which she and Latif directed in 1968, featured Yogesh Bali, Meena Rai, and Ravikant.

After Latif passed away in 1967, she continued to remain associated with the film industry. One of the most impactful films in Indian cinema on the Indo-Pak partition - Garm-Hawa (1974), was based on her unpublished short story, written for film by Kaifi Azmi and Shama Zaidi. Revolving around a Muslim businessman and his family who struggle for their rights in a country which was once their own, the M S Sathyu directorial starred Balraj Sahni, A K Hangal, and Geeta Kak.

In 1979, she penned the dialogue for Junoon, the Shyam Benegal directed drama film set during the 1857 War of Independence. It depicted an obsessed Indian nawab who desires to wed a young Anglo-Indian woman, but the girl's obstinate mother stands between them. She also appeared onscreen in the film, playing the maternal grandmother of Ruth Labadoor.

She penned the dialogue of Mahfil (1981) directed by Amar Kumar and written by K A Abbas. The romantic action drama starred Ashok Kumar, Sadhana, Anil Dhawan and others.

In 1975, she directed a documentary titled My Dreams.

She is also credited with writing the stories of the teleserial Chouthi Ka Joda (1984) and the TV film Yaar Julahay (2021).

Alongside her film projects, Chughtai continued writing short stories and novels; her fourth collection of short stories Chui Mui (Touch-me-not) was released in 1952 to an enthusiastic response. Her novel Tedhi Lakeer has come to be regarded as Chughtai's magnum opus and is considered to be one of the most significant works of Urdu literature. Through the novel, she presents a word picture of the way Indian Muslims lived under the colonial rule, and explores their struggles and desires. This quasi autobiographical work provides a commentary on the state of the country just before Independence.

Her novel Dil Ki Duniya is regarded as second only to her Tedhi Lakeer. It follows the lives of a varied group of women living in a conservative Muslim household in Uttar Pradesh. Both were largely autobiographical in nature as Chughtai drew heavily from her own childhood in Bahraich, Uttar Pradesh. Her 1970 novel Ajeeb Aadmi was said to have been based on the life of film actor Guru Dutt Released in the early 1970s, her novels Ajeeb Aadmi and Jangli Kabootar made use of her knowledge of the Hindi film industry, which she had been a part of for a prolonged period. Jangli Kabootar followed the life of an actress and was partially inspired from a real-life incident that had occurred at the time, while Ajeeb Aadmi similarly narrates the life of Dharam Dev, a popular leading man in Hindi cinema, and the impact that his extramarital affair with Zareen Jamal, a fellow actress has on the lives of the people involved. Ajeeb Aadmi was been widely praised even in contemporary times; Mumbai-based writer and journalist, Jerry Pinto said of it, “There hadn't been a more dramatic and candid account of the tangled emotional lives of Bollywood before this,” while writer-director Khalid Mohamed called it a first of a kind tell-all book about the Hindi film industry, one that was “an eye-opener even for the know-alls of Bollywood.”

Her work earned her many important awards and prizes from government and non-government organisations. In addition to the Padma Shri which she was awarded in 1975 by the government of India, she was awarded the Iqbal Samman, the Ghalib award, and the Filmfare award.

Diagnosed with Alzheimer's disease in the late 1980s, which limited her work thereafter, Chughtai passed away at her house in Mumbai on 24 October 1991, following the prolonged illness. She was reportedly cremated in keeping with her wishes, having recorded her fear of being buried – “I am very scared of the grave. They bury you beneath a pile of mud. One would suffocate [...] I'd rather be cremated.”

Her status as a writer has risen further in more recent times, following the translation of numerous of her works into English, a renewed interest in the Urdu literature of the twentieth century, and subsequent critical reappraisals. Despite having established herself as a significant voice in Urdu literature, Chughtai remained keen on probing new themes and expanding the scope of her work. Her signature skill in her writings remains her unique style of expression. She is celebrated for using language not only as a means of expression in her stories but also an abstract truth in itself. She remains an integral figure in Urdu literature, with her works continuing to initiate discussions; in fact, no discussion about feminist literature or women authors is complete without her.

.jpg)