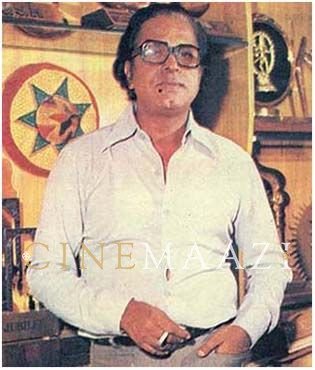

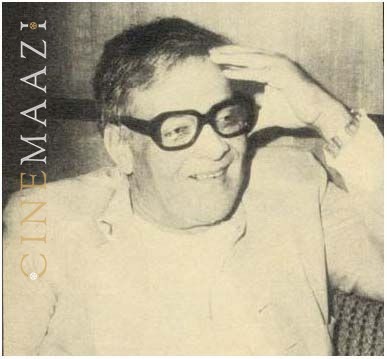

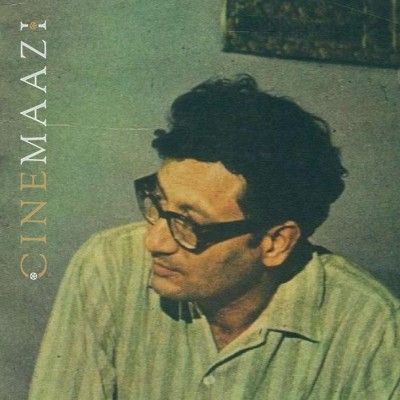

Dr Rahi Masoom Reza

Subscribe to read full article

This section is for paid subscribers only. Our subscription is only $37/- for one full year.

You get unlimited access to all paid section and features on the website with this subscription.

Not ready for a full subscription?

You can access this article for $2 , and have it saved to your account for one year.

- Born: 1 September, 1927 (Ghazipur, United Provinces, British India)

- Died: 15 March, 1992 (Mumbai)

- Primary Cinema: Hindi

- Spouse: Nayyar Jahan

Rahi Masoom Raza, one of Urdu's finest writers, is also an icon of the Hindi film industry. He penned the dialogues of popular and well-appreciated films such as Mili (1975), Alaap (1977), Gol Maal (1979), Karz (1980), Judaai (1980), Hum Paanch (1980), Anokha Rishta (1986), Baat Ban Jaye (1986), Naache Mayuri (1986), Awam (1987), Lamhe (1991), Parampara (1992), and Aaina (1993). Among his body of memorable work, he also penned the dialogue for the successful teleserial, Mahabharat. Questioned by fundamentalists about how a Muslim could write the dialogue for a Hindu epic, Raza, a highly educated, secular, progressive Muslim, had responded: “I am a son of the Ganga. Who would know the civilization and culture of India better than I?" He also penned the lyrics for the songs of Alaap (1977), and Des Mein Nikla Hoga Chand (Jagjit Singh & Chitra Singh). Raza had acquired a PhD from Aligarh Muslim University, and even lectured in the Urdu department, before he sought his livelihood in cinema in 1967, where he remained an intellectual in the commercial film industry. Working in over 300 films, literature remained Raza’s enduring love. He won the Filmfare Best Dialogue Award for Main Tulsi Tere Aangan Ki (1978), as well as Mili (1975) and Lamhe (1991).

Born on 1 September, 1927 in Gangauli, Ghazipur, a city on the banks of the Ganga in eastern Uttar Pradesh, he hailed from a highly educated family; he was the younger brother of educationist Moonis Raza and scholar Mehdi Raza. His father was a leading civil lawyer who refused to leave for Pakistan at the time of Partition. As a child, Raza was struck by TB and polio, leading to extended periods of bed rest, which were enlivened by stories narrated by the family retainer, Kallu Kaka. He would also read books at home and from the local library, including Urdu translations of the Mahabharat and Ramayan. Overcoming the roadblocks, he completed his higher studies from Aligarh Muslim University, and went on to acquire a doctorate in Hindustani Literature. Pursuing a career in literature, he penned novels under the pseudonym Shahid Akhtar for an Urdu magazine Rumani Duniya from Allahabad. He then went on to become a lecturer in Urdu at Aligarh Muslim University before moving to Bombay in 1967.

Work was not easy coming and the early years were particularly difficult; however, Raza went on to carve a most successful career for himself in the film industry as a writer. He worked in over 300 films, penning dialogues for films such as Alaap (1977), Gol Maal (1979), Karz (1980), Judaai (1980), Hum Paanch (1980), Anokha Rishta (1986), Baat Ban Jaye (1986), Naache Mayuri (1986), Awam (1987), Lamhe (1991), Parampara (1992), and Aaina (1993). He wrote the screenplays for films and teleserials such as Neem Ka Ped, Kissi Se Na Kehna, Main Tulsi Tere Aangan Ki, Disco Dancer (1982), and Mahabharat (1988-90). While he was especially appreciated for his work in Mili, Gol Maal and Lamhe, working closely with filmmakers like Raj Khosla, B.R. Chopra and Hrishikesh Mukherjee, his penning of script and dialogues for the TV serial, Mahabharat brought him immense attention. Based on the epic, the Mahabharata, the serial became one of the most popular TV serials of India, with a peak television rating of around 86%. Incidentally, when B R Chopra requested Raza to pen the epic serial, certain self-styled protectors of the faith criticised Chopra for assigning the same to a non-Hindu. An avid champion of India’s syncretic culture, Raza responded: “I am a son of the Ganga. Who knows the civilization and culture of India better than I do?”

Firmly opposed to fundamentalism of every kind, Raza wrote about the Hindu-Muslim relationship, or about being a Muslim in India, with deep understanding. In his novel Os Ki Boond he wrote of how there hadn’t been a communal riot in Ghazipur since 1932. He believed that religion should never be allowed to intrude into politics because Indian society was not the fiefdom of any religion. In the book Khuda Hafiz Kehne Ka Mod, a collection of essays and articles published in magazines from 1972-92, he wrote, “Slowly I am developing a hatred for religion…I am an angry person... Shri Bal Thackeray says I am not a Maharashtrian because Marathi is not my mother tongue…And the RSS says I am not even a Hindustani. I will have to become a Bhartiya/ Indian.”

While Raza earned a living via films, he did not neglect his first love—literature and poetry. The novels he penned featured the Hindu-Muslim theme. His masterpiece Adha Gaon depicts the Shia community of landlords in Gangauli village over the decades, with the wound of Partition slicing the narrative. The book questions the idea of Partition and nationhood based on religion. His Topi Shukla depicts the friendship between Balbhadra Narayan Shukla and Mirza Jirgam Ali Aabdi, both of whom are incomplete without the other, while Os Ki Boond looks at a Hindu-Muslim communal riot post-Independence. His Scene No. 75 was a dark humoured and brilliant look at the underbelly of the Hindi film industry. His poetry collections include Mauz-e-ghul mauz-e-saba (Urdu), Ajnabee shahar: ajnabee raste (Urdu), Main ek Feriwala (Hindi), and Sheeshe ke Makaan Wale (Hindi).

On the personal front, he was married to Nayyar Jahan. As she had been previously married, Raza was dissuaded by many to break off ties. He remained firm in his resolve and the couple was married, leading to a controversy that compelled Raza to leave the Aligarh Muslim University, where he was serving as a temporary lecturer, and further move to Bombay to work in films.

Interestingly, despite being an avid poet, he stayed away from mushairas or poetic gatherings, post marriage. This was apparently a condition imposed by his wife in return for her having to give up her passion for horse-riding, which Raza had pleaded with her to, after she had taken several falls and suffered injuries! Both kept to their respective sides of the bargain till the end.

Rahi Masoom Raza passed away on 15 March, 1992. Regarded as nothing less than a national treasure, ‘a scholar who strayed into Bollywood’, his contribution to literature, poetry and films remains enormous.

References

Sources: https://www.imdb.com/name/nm0713592/

https://www.livemint.com/Leisure/kqMnNxSh7PTtusZLzVYjmO/Rahi-Masoom-Raza-Hindustani-at-heart.html

https://thewire.in/books/rahi-masoom-raza-scholar-who-strayed-into-bollywood

.jpg)