This section is for paid subscribers only. Our subscription is only $3700/- for one full year.

You get unlimited access to all paid section and features on the website with this subscription.

Subscribe to read full article

This section is for paid subscribers only. Our subscription is only $37/- for one full year.

You get unlimited access to all paid section and features on the website with this subscription.

Not ready for a full subscription?

You can access this article for $2, and have it saved to your account for one year.

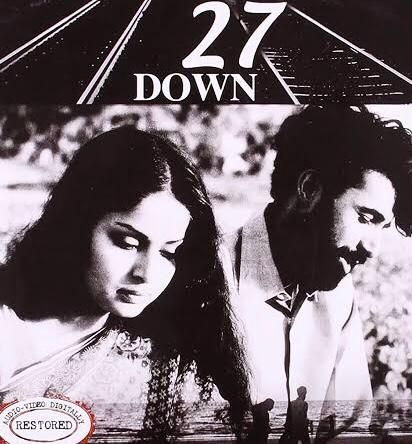

- Release Date1974

- GenreDrama

- FormatB-W

- LanguageHindi

- Run Time123 min

- Length3354.02 meters

- Number of Reels14

- Gauge35 mm

- Censor RatingU

- Censor Certificate Number74157-MUM

- Certificate Date31/12/1973

How do you know that you’ve reached somewhere in your life? And why does life feels like a perennial state of traveling with neither a starting point nor a destination? In 27 Down, Sanjay’s troubled mind is conflicted with such questions. He feels like he is surrounded by nothingness. He is in a constant state of departure while never arriving anywhere. There is a feeling of desolation in the lives of the movie’s characters, who are trying to escape something in their existence. They are aware of their misery but cannot locate its source, which leaves them in a state of constant introspection and aloneness. Sanjay has a life and a story which is going in its own direction on a particular track, towards an unknown destination. His life is a culmination of the burdens and happiness from his past and the ambiguity of his present circumstances.

Sanjay feels intimidated by his authoritarian father but also admires him for being an engine driver. He is fascinated by trains and wants to become an engine driver when he grows up. One day, an accident forces his father to retire prematurely. As Sanjay grows up, he loses his curiosity in trains but he still fears his father. He opts for art school. While studying in college, he is somehow convinced by his father about leaving his education and apply for a job in railways. After numerous protests, he abandons all his hopes and ambitions. Soon, he is forced to pursue a stable yet claustrophobic life of a ticket inspector, where he has the perks of free traveling and housing. The last traces of subversion in his life fades into the anonymity of his uniform and he gives in to the life of a ticket inspector, crossing one bridge after another, through endless tunnels with a sense of detachment. The monotony of his life is suddenly shaken by a beautiful commuter named Shalini, who works in Life Insurance Corporation as a stenographer. Both of them feel lonely in their lives and it induces empathy in them for each other. Their relationship flourishes, as they keep meeting each other in railway compartments, stations, cafés, beaches, and her apartment.

Sanjay’s father comes to know about his ‘indiscretions’, and calls him back home on a pretext of illness. His father arranges his marriage to a rich landowner’s daughter. Sanjay receives cash, furniture, four buffalos, and the bride’s old illiterate father in dowry. His wife comes to know about Shalini through one of his friends. She incessantly bothers him by asking questions about her. Sanjay feels suffocated because of his wife’s constant inquiries and crassness. One day, he coincidently encounters Shalini. This unexpected encounter leaves him in a state ambivalence and he decides to leave everything behind. He randomly takes the ‘27 Down’ train to Benaras with no hopes of reaching anywhere. Sanjay tries to start a new life. He tries to forget his old self and introspects the meaninglessness of his existence through alcohol, prostitutes and aimless strolls in the streets of Benaras. The hopelessness of his brief endeavor of seeking freedom again takes him back to the 4 buffalos, a disappointed wife and the shrewd father-in-law. He couldn’t hold his agony and meets Shalini with the hope of reviving their unrequited love. But Sanjay’s abandonment and time has made Shalini numb. She couldn’t reciprocate to Sanjay’s expectations.

They decide to meet again but it never materializes. Sanjay feels exhausted and defeated. He can’t shake the feeling of being in constant movement towards nowhere. He desires to forget his emotions and everything that makes him feel anything in the first place. He wants to rest so that he could meander into numbness, and go back to nothingness.

27 Down suggest a feeling of desolation, the emptiness that follows a period of intense happiness. Like a train disappearing into the dusk, leading nowhere. The film has the dark foreboding of an approaching tunnel.

In relating the train to the inevitability of one’s life, the director traces the mind of a troubled, sensitive, and cynical young man, Sanjay. His life is lived literally on a train. Since childhood, he has been in awe of his father, who was an engine driver (an accident forced him to retire prematurely).

Sanjay grows up. He opts for art school. His love for trains has worn off but not the fear of his father. Father and fate conspire to get him back on the right track- the railway ones.

He is inducted into the secure, claustrophobic life of the railways. Despite Sanjay’s protests, the father decides that “facilities” like free travel and housing are not to be disregarded. Leaving art school, Sanjay becomes a ticket inspector on a train.

Whatever hopes and ambitions Sanjay might have had are soon forgotten. He is swallowed up by the railways, engulfed in their sooty, choking grasp. His casual attire gives way to the anonymity of the ticket-inspector’s uniform. The last traces of rebellion vanish. He has accepted the “system”. Life falls into a rut, a monotonous pattern.

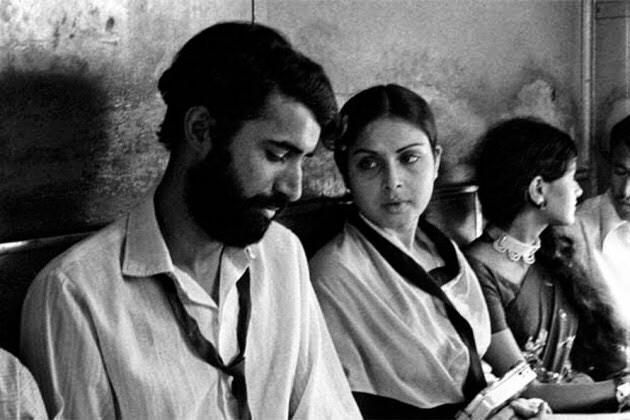

Fate intervenes in the form of a beautiful commuter, Shalini, a stenographer working with the Life Insurance Corporation (a symbolic job, one presumes). There is instant empathy between the two lonely people. Their love blossoms in railway compartments, refreshment rooms, beaches, and her bed-sitter apartment. For Sanjay, life gains a purpose, a sense of anticipation and excitement. Even the monotony of train journeys is now tinged with nostalgia.

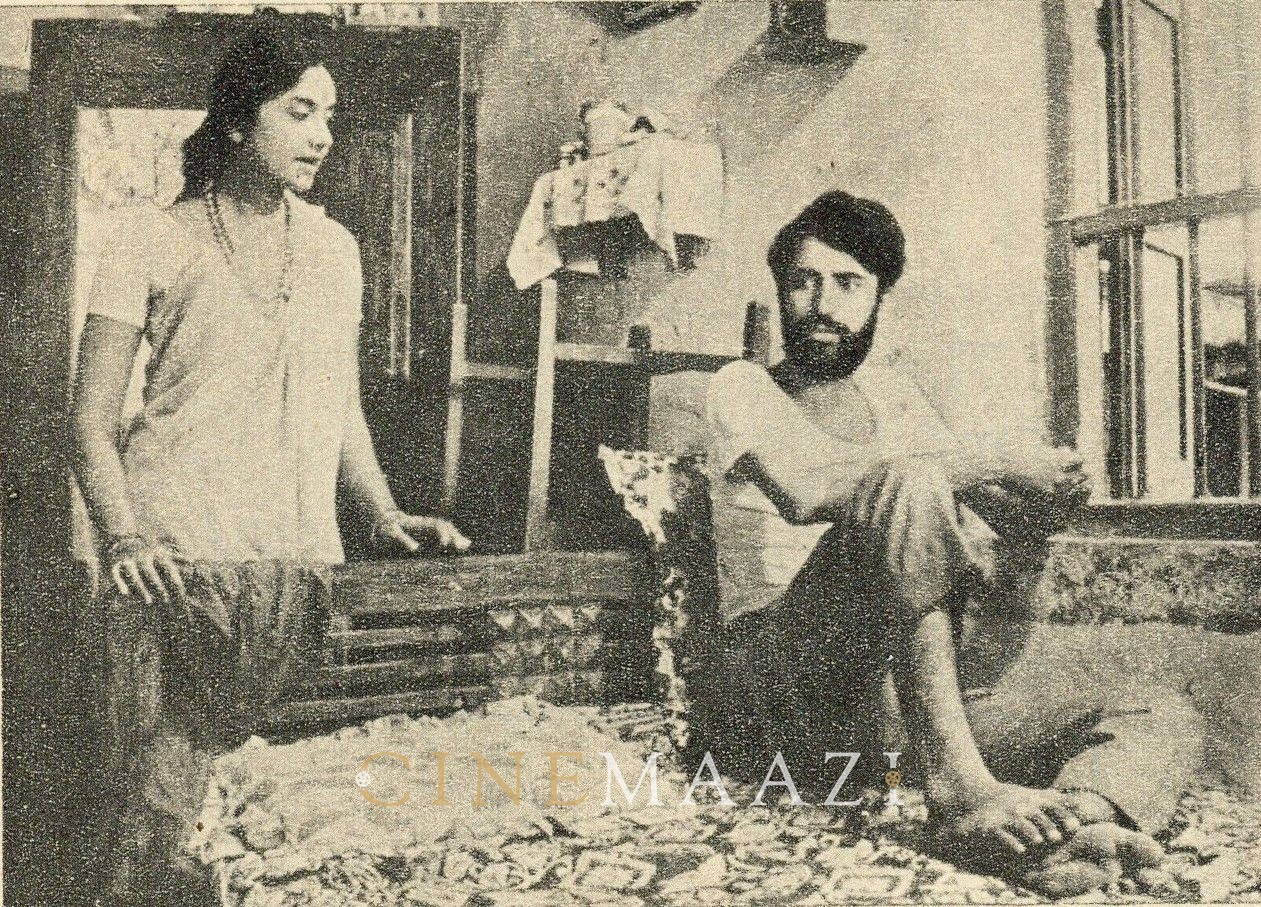

The brief encounter is destined only to be a respite. The father decides it is time to put an end to his son’s “indiscretion”. He recalls him on a pretext of illness. The boy is summarily married off to a rich shrew who is saving her virginity for the wedding night. She explores the myth of the shy, modest village belle and hurls herself on the dispirited groom. Her dowry includes, besides cash and furnishing, four buffaloes and an old, illiterate father. The wife chatters incessantly stupidly, going on at him about his earlier romance. Sanjay is increasingly repulsed by her crassness.

A chance encounter with Shalini makes him realize his loss. What has made him behave so irrationally, he asks himself. The claustrophobia is stifling. He has to get away from it all.

He takes the “27 Down” train to Benares. Any place is good enough. He finds a sense of release. The booze, the whores, the hills, all assists in his introspection.

He tries to discover the meaning of life. For a while, he believes that life will take a new direction. But seemingly without a will, he returns to his destination…-back to his wife, the buffaloes, the stench, the father-in-law.

In desperation, Sanjay seeks out Shalini. It is hopeless. She is not the same person anymore. She reacts coldly, without any feeling. He persists. Can the past return? Why don’t they try and work something out? They plan a meeting, which does not materialize.

He is tired, exhausted by constant movement leading to noting. He wants to rest now, to let his senses drift into numbness. He moves back into nothingness.

[Source: Film Profile as a reproduction from Film India, The New Generation 1960-1980, Directorate of Film Festivals, 1981]

It is difficult to evaluate the work of a person who has left behind only one film. Reviews, of course, are a transitory thing. But one feels happy when ‘Slight & Sound’ praises 27 Down’s intelligent use of locations. True, Kaul displays a mature style in his first film. One can gauge what could have been in his mind when one remembers that his greatest sorrow was that he could not get a film to make for the National Film Board of Canada.

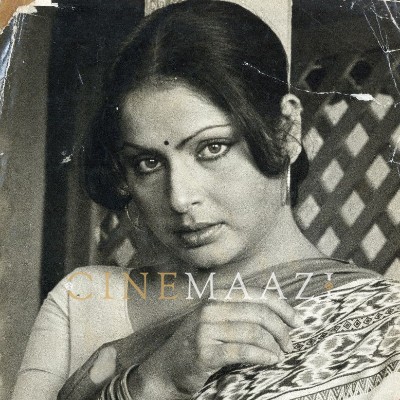

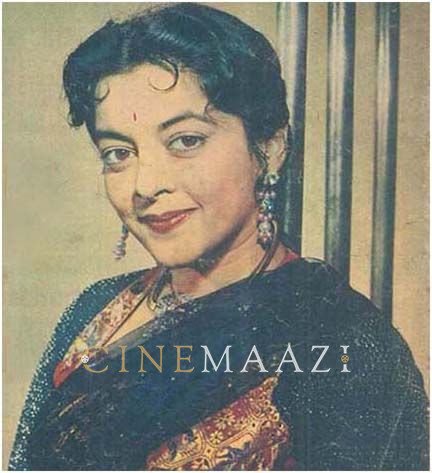

The working woman, Shalini who questions Sanjay’s acquiescence. 27 Down is one of the earliest of the new films in which a film star of the caliber of Raakhee plays a lead role.

About a young man who is forced by an injury to his engine-driver father to join the railways instead of studying art, it makes wonderfully imaginative use of trains, tracks, and aimless journeys that echo his despair. A little too long, a little too self-indulgent, it is nevertheless a strikingly intelligent piece of work.

Cast

-

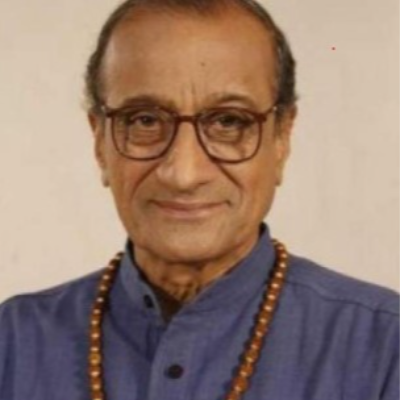

M K Raina

Sanjay -

Rakhee

Shalini -

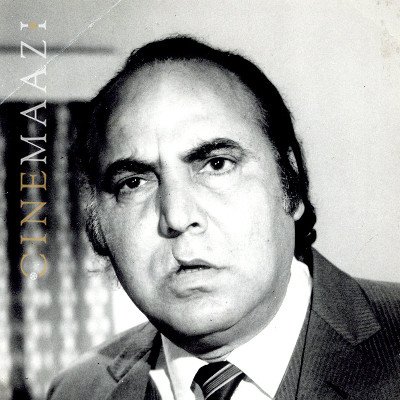

Sudhir Dalvi

Sanjay's Friend -

Rekha Sabnis

Sanjay's Wife -

Om Shivpuri

Sanjay's Father -

Nilesh Velani

Young Sanjay

Crew

-

BannerFilm Finance Corporation

-

Director

-

Producer

-

Music Director

-

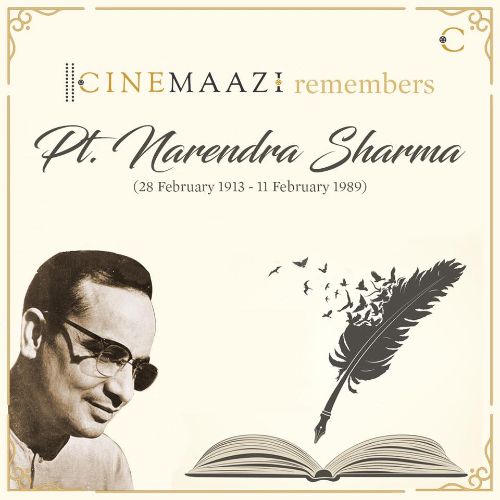

Lyricist

-

Story Writer

-

Screenplay

-

Cinematography

-

Editing

-

Sound Recording/ Audiography

-

Art Director/Production Design

-

Production Controller

-

Costumes

-

Re-recordist/ Sound Mixing

-

Laboratory/ Processed atFamous Cine Lab, Tardeo

.jpg)