To Be a Woman

Subscribe to read full article

This section is for paid subscribers only. Our subscription is only $37/- for one full year.

You get unlimited access to all paid section and features on the website with this subscription.

Not ready for a full subscription?

You can access this article for $2, and have it saved to your account for one year.

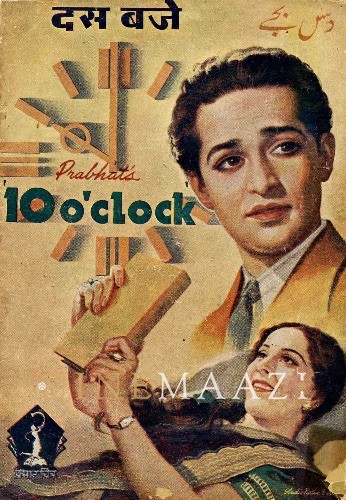

The business of film is to create images. The more populist the image, the more potent its mythical, seemingly indestructible life. Woman's response to popular cinema is a ceaseless love-hate thraldom because the film image ostensibly celebrates her eroticism while reducing her to a passive sex object. The space in which the screen woman is filmed, the way her body is fractured and is commodified into an object for the overwhelmingly male gaze, all thrust her even more irrevocably into depths of involuntary thraldom.

Critics - not all of them women - have recognised the all-pervasive male gaze which consumes this eroticised commodity. What is even more subversive to women's self-image is their own willing submission to this insidious, attractively packaged image. This is because even the crassest of populist cinema invokes the incantatory magic of ritualised iconography, the infiltrating potency of myth, the seduction of song and the sanction of societal approval. That is why women's response to this image resembles a nightmarish chase after a mirage that pretends to be a mirror. It is a mirror that also promises to educate and reward.

Popular cinema creates instant mythologies for uncritical consumption and not histories of credible people. This is truer of the heroine than the hero. Hindi cinema is so driven by its phallocentricity that its heroes inevitably acquire larger-than-life dimensions with archetypal overtones. You have the good-son-bad-son dichotomy, the lone warrior, the dispossessed son claiming his patriarchal inheritance, the avenging destroyer, the dutiful monogamous husband and the dark god of playful eroticism who scatters his seed. Not too many types, elements are combined by enterprising scenarists.

The heroine is straight-jacketed into a chaste wife whose suffering can only make her more virtuous, the nurturing mother who denies her own self, an avenging Kali or a titillating strumpet. And yes, the eternal worked victim, usually waiting for a male saviour. Hindi Cinema in the '80s and '90s has really not progressed beyond these comfortable, easily identifiable stereotypes. The true archetypes of popular cinema are only two despite all the flurry of films flaunting female avenger avatars in the mid and late '80s. One is Mother India's (1957) matriarch who is the upholder of dharma and the true emotional centre of the hero's life. The second is Pakeezah (1972), the romanticized apostrophe to woman as the pathetic, impossibly innocent Other to be rescued from the penumbra of social opprobrium. Every tawaif and her cousin is descended from Pakeezah and is a wan reflection of pale, derived poetic pathos. And every strong mother, sternly casting out her erring son, is Mother India's daughter. The only difference being that the Rakhee of Khalnayak (1993) is denied the moral stature and heartbreaking courage of Nargis. She cannot shoot down her erring son who has now graduated from village rebel to brainwashed terrorist, bent on destroying the nation.

The gradual decline in the moral authority of the mother was first visible in Amitabh Bachchan's angry heroics till she was reduced to a sentimental, ineffective figure. Yes, there have been exceptions when the mother regained her earlier stature as in Agneepath (1990). It helped that Rohini Hattangadi still carried her Kasturba halo from Gandhi (1982), readily invoked by dress and demeanour.

If the decline of the mother's authority was a reflection of the ongoing sociological reality - the disintegrating joint family - this authority was not immediately transferred to the wife in the emerging nuclear family. It only enhanced the hero's loneliness, umbilically severed from his Oepidal dependence. A few nostalgic family melodramas surfaced now and then, the educated young woman, who demanded that she come first in the husband's life, was the misguided destroyer of family harmony. Some films like Ghar Ghar Ki Baat (1959) regressed all the way back. Its beautiful, educated heroine was made to mouth how a woman finds nirvana in carrying out the meanest of household chores and wallows in servitude to the husband, exulting in total submission to a culture that makes India great (the heroine's words). She totally rejects the independent working woman as a wrecker of homes.

A curious variation of the mother-worship cult is Beta (1992). It tells of a war where no weapon of subterfuge is taboo as the tough, modern young bride takes on the wily cunning of an evil step-mother-in-law. The setting is rural and the ambience rustic Nawabi. The hero is an uneducated simpleton who literally worships his conniving step-mother and will not brook any diminishing of her authority in a household where the rightful patriarch has been shut up as insane. Madhuri Dixit plays the determined middle-class girl whose marriage to the hero is brought about by circumstance rather than her volition. She is stern and seductive by turns... a Menaka tantalizingly dressed in saffron (baring a vast expense of gyrating midriff) heaving to the Dhak dhak karne laga beat and sending the hero (and the audience) into tumescent stupor. As the new bride, she matches wits with the older woman and delight. The viper of a mother (is aptly named Nagmani) nearly devours her trusting son and yet, the deification of motherhood is so potent that it pierces her wicked heart so that mother and son are clasped in a late Oepidal embrace. The daughter-in-law fights the battle not to assert her rights but to restore the household to its proper patriarchal functioning. Madhuri is a shackled Savitri, owing more to the popular fictional heroine of Swayansiddha (1975) (and films based on this theme) than the awesome Puranic archetype, for Savitri has the courage to outwit Yama, the god of death.

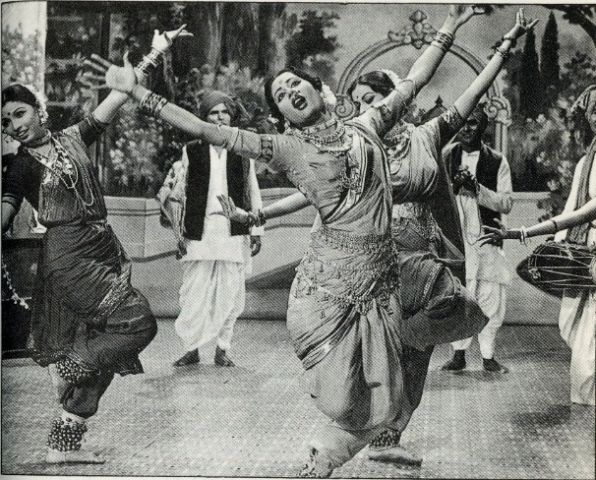

New levels of permissiveness have obliterated the strictly enforced divide between the heroine and vamp. The rigid dress code disappeared as nubile heroines cavorted in itsy bitsy fluff, disported in diaphanous saris under waterfalls or studio-made rain, strutted in skin-tight dresses or undulated their navel-baring torsos in ethnic cabaret wear of sequinned, clingy figure-hugging saris. She danced with the seductive abandon of houri as the camera routinely zoomed in on one body demure sari towards the end as she attained the highly desirable wife status. It was Manu being updated all over again: westernised harlot before the wedding and chaste wife after. The autonomy, grace and dignity that popular cinema of '40s and '50s had given its heroines were gone in the pursuit of the bitch-goddess of box-office success.

Nothing personifies this frenzied, yet calculated, pursuit more than Khalnayak which trivializes not only the legacy of Mother India but diminishes the stature of the dissenting son into that of a gullible clown. For all its political posturing, and so-called contemporaneity, this over-long, uneven pseudo-epic dresses the eminently salable charms of its heroine in the come-hither seduction of rustic raunch and the titillating suggestion that the pure heroine could be attracted to the disreputable villain. The knowing smirk behind Choli ke pichhe kya hai?, provocatively posed by the husky, put-on masculinity of the gypsy voice of Ila Arun is answered not so much by the innocuous lyrics but the collage of fragmented body parts an orgasmic camera puts together with such voyeuristic relish. The choreography plays with the juxtaposition of suggestive opposites: the all-enveloping veil followed by the bare skin under the backless choli. There is much heaving of thrusting breasts and wildly undulating midriffs. Sanjay Dutt's prominent eye patch draws attention to revetted male gaze for whom Madhuri Dixit is displaying all her not-so discreetly veiled charms.

A New Look

It was left to parallel cinema to give women their cinematic due. When not preoccupied with depiction of poverty or middle-class angst, or the pure joy of experimenting with cinematic language, sensitive filmmakers focussed on the changing man-woman relationship in the flux of social turmoil. Basu Bhattacharya, Shyam Benegal, Kalpana Lajmi, Aparna Sen, Ketan Mehta and Kumar Shahani...all these filmmakers had their particular preoccupations and their own distinct approach to cinema. What is common to all is the sincerity of conviction and empathy for women, complex entities and not cardboard stereotypes, caught in the throes of a new morality.

Kumar Shahani's preoccupation with the epic mode made him see women as inheritors of archetypes. The Smita Patil of Tarang (1984) metamorphoses into the celestial Urvashi, from the earlier sentient being rooted in the working class and imbued with radical aspiration. The politics of radical ideology creates its own mythology and mints its new icons. In Kasbah, the female protagonist, played with swaggering grace and intelligence by Mita Vasisht, uses her sexuality to drive a hard bargain in the market place of familial relationships. Shahani's archetypal invocations are impalpable emanations of a highly complex narrative text. They seem to scorn the more immediate task of audience identification.

Basu Bhattacharya and Shyam Benegal have brought palpable empathy and even tenderness on occasion to their female characters. Bhattacharya's lonely urban women coming to terms with their aspirations of clearly defined selfhood and yet desperately seeking the warmth of man-woman bond are, in a way, highly romanticized. yet, the wife in Anubhav (1971) has a rare concreteness due as much to Tanuja's strong presence as the sympathetic script. Panchvati (1986) explores the undercurrents of forbidden sexual attraction in a joint family situation, where a sensitive painter is drawn to her husband's older brother, who is made of finer grain than the crass young man she has married.

Panchvati is a far cry from Charulata's (1964) elegant perfection and intuitive understanding of a woman's loneliness. Yet, Deepti Naval's doe-eyed, fragile sensitivity captures the tragedy of marriage to the wrong man and celebrates the one memorable night which consummates the marriage of true minds. But instead of exploring the pain and fulfilment of this relationship, Bhattacharya loads his film with overt symbolism and laboured mythological references that fuse diverse epics most successfully.

Shyam Benegal has earlier used woman's sexual exploitation as a wider metaphor for the evils of feudalism which fought off the advent of modernity with a savagery born of the need to survive. Mandi (1983) was an uneven black comedy that missed a log of its intended punches. But it had an unsentimental feel for the prostitutes who made their own separate bargains with respectability and approached their trade with matter-of-fact pragmatism. Shabana Azmi played the madame who really cares for her girls with a sort of gruff tenderness and yet can starve an unwilling novice into submission. Benegal imbues the first half of the film with the subtle nostalgia for a more elegant past when the kotha was a place of refined literary discourse and the tawaifs were keepers of courtly poetry. The frisson of latent lesbian yearnings - Shabana's protective tenderness for the virginally coquettish Smita (waiting for the highest bidder) - sits awkwardly like a stiff organdy frock on the sinuous silks the girls are draped in!

It is Bhumika (1977) that remains a true milestone. The Usha of Bhumika is born rebel looking for a cause as well as a prisoner struggling against her circumstances. Usha's rebellion is against her sexual confinement and exploitation by her manipulative husband who sees her as a meal ticket for life. Her dilemma is highly ironic because she is an actress doomed to play a variety of roles but confused about her own role in real life. She is exploited by the husband (who was also her mother's lover and we have the first intimation of near-incest) as well as the film industry which tries to mould her charms into saleable stereotypes for mass consumption. Usha's search for sexual fulfilment and emotional security drives her restlessly into the arms of many men who don't and can't measure up to her demands. Each of them is using her in his own way or forcing her into her yet another male-cast mould.

Usha's final lesson is to learn a bitter truth: like all complex individuals with a highly charged emotional drive, she must learn to live alone. After such knowledge, what forgiveness? Usha may not have found the road to forgiveness but she wrests a hardwon tranquility after her rage is spent. Benegal bestows the combined aura to two mythological allusions on his actress-protagonist who is already subjected to the instant mythologies that popular cinema spawns. The heroine's given name is Usha and her screen name is Urvashi. In her are joined the Rig Vedic deity of dawn as well as the later legend of Apsara Urvashi, in search of human lover Pururavas. The fusion of two iconic image is validated by historian D.D. Kosambi's observation that Urvashi is a later metamorphosis of Usha. These intimations of mythic immortality enrich Bhumika and add an ironic poignance to Usha's volatile vulnerability, born of her inchoate rage restless passion.

Smita Patil's vibrant intensity and earthy yet frail sensuousness lit up a host of films, giving them a tragic afterglow. In Jabbar Patel's Umbartha (1982), she paid the emotional price for her commitment to work. In Ketan Mehta's flamboyant Mirch Masala (1985), her flaming defiance and challenging sensuality roused a whole village to rebellion. Even as she played the rebel, Smita Patil's sensuality was an integral part of the persona. She was never made to deny her sexuality as the cardboard rebels of commercial cinema were made to.

Recasting the Mould

It was in the '80s that Hindi cinema discovered the new angles of death in variations of the rape and revenge formula. Whether it was a clever response to the articulation of women's anger at increasing violence or a desperate clutch at novelty, filmmakers had front-ranking stars clamouring to play the dacoit queen taking to a gun, or a female vigilante sworn to vengeance after the trauma of rape. Whatever the setting and whoever the star, this sub-genre immediately dictated its dress code to fit a new formula. Either the heroine or someone close to her is raped by a marauding dacoit or a gang of city goons. She discards overnight her coy village belle tricks, along with constricting lehangas and girlish braids embellished with tinsel tassels. She quickly finds a male mentor who could be a surrogate father or well-meaning lover for initial guidance. Her seductive form is poured into skin-tight black leather jeans, high boots and even a whip to chastise the villain. Does she cater to our talent sado-masochistic longings, however, western-inspired her image? This image teems with tantalizing, self-contradictory possibilities.

For instance, in Sherni (1988), Sridevi virginally braided locks are let loose in flowing abandon (when she is physically unpossessable) to tease and torment the collective male gaze. This complements her all-black, brass-studded leather outfit. A message of forbidding, alien sexuality that thaws into the familiar cosy warmth of the seductive mujra dancer, a disguise she dons to trap one of the villains. It is as if the unfamiliar image has to be periodically stripped of its alien accoutrements to reassure us of her docile Indianness and its promise of sexual submission to the patriarchal order. In only one film, Khoon Baha Gang Mein (1988),does the heroine switch to dhotis from her lehangas. And all the heroines must have names that invoke Kali, Durga and any other form of Shakti. Why, you even had Hema Malini astride a lion, posing as the deity in a temple, draped in flaming red sari and wielding the awesome trishul. This easy invocation of ready-made mythology is accompanied by the same bombastic rhetoric declaimed by the hero preliminary to destroying the villain-in-chief.

Among all these films, only two merit detailed examination for the subtext that negates the film's stated pro-woman stance. Zakhmi Aurat had an efficient, dedicated woman police office for protagonist. Played by the stunningly beautiful Dimple Kapadia, the heroine is shown in her uniform, riding phallic motorbike and her glorious hair bundled under a cap. Her zeal in capturing a few minor rapists ensures her gang rape at the quartet of villains with high connections. The rape sequence highlights the agony in her eyes as she stares at the ceiling fan from which dangle a pair of jeans. Her own or the rapists' is not clear. But earlier, they are shown clawing at her trousers as she runs to escape them. The visual reading of sequence implies punishment for daring to flaunt male accoutrements of office.

Pratighat (1987) had a non-glamorous protagonist who was depicted as the housewife next door till her public disrobing and subsequent humiliation rouse her to wrath. She walks out on her cowardly husband and aborts the child she has been carrying, not because she wants to assert her right over her body but to free herself for action. Earlier, the films establish that heroine defines her sexuality in terms of motherhood. What the film says in effect is that for a woman to be able to act in society and redress grievous wrongs, she must sacrifice her femininity. The heroine also uses the axe, usually a male weapon associated with a wrathful Parashuram, to behead the villain who has corrupted the body politic. It is revealing that even a matronly protagonist must voluntarily destroy her sexuality to be a free agent.

The recent films have tried variations on the woman as rebel with varying degrees of success. Raj Kumar Santoshi's Damini (1993) aims to be a conscience-raising exercise of waking the middle-class out of its congenital apathy to injustice. The eponymous heroine is uncomfortably committed to speaking the truth even when this endangers the reputation of her rich in-laws. Damini has seen her loutish brother-in-law and his friend's gang rape the maid during Holi. Her lower-middle-class values subdue her conscience for a while as she gives in to the combined persuasions of her uppity in-laws and the dilemma that her husband, a really decent man, is caught in. But the script loads the dice against Damini and incarcerates her in a mental hospital where she is terrorised and certified insane. Tapping into the ready availability of mythological reference, the drums of Durga puja send Damini into a frenzied tandav and this shocks her out of a near-lobotomised lethargy.

The director, even as he valorises the heroine as the uncompromising fighter for justice, takes care to showcase her maidenly charms earlier on, inviting Meenakshi Seshadri to prance and preen, to rhythms folksy as well as the kitsch that passes for filmi classic. The real heart of the conflict - a traditionally brought up Indian woman's dilemma when her principles clash with family loyalty - does touch a responsive chord. It is this theme that rings true for ours in a society in a state of flux where old certitudes no longer exists an individuals have to find their own scale of values. Damini empowers a woman and celebrates her integrity even though the narrative is enveloped in the usual safety net of familiar assurances about Damini's earnest endeavour to be a good daughter and good daughter-in-law. It is her in-laws, whose wickedness is enlarged to incredible proportions, who don't deserve her. Damini is, at any rate, a change from the usual brainless bimbettes let loose to satisfy collective voyeurism.

Khalnayak may be calculated remake of a Hollywood horror thriller (a genre alien to our soil in which sentimental piety thrives) and gratuitously inserts yet another, far more obscene choli song. For all that, this Sawankumar Tak film has enough significance (intended and otherwise) leaking into the text that it offers rich pickings to the interested viewer. The director can't really make up his mind as to what constitutes a heroine. Jaya (Jayaprada), for all that she looks like a well-preserved society matron, is soon reduced to the status of an anaemic and asthmatic mother - thus conforming to our society's deep seated fears regarding male doctors examining women - but the anti-heroine Anu (Anu Agarwal) taunts her as a woman who can't satisfy her husband (naturally, a virile specimen whose desirability is not diminished by fatherhood!). Even Anu's deviously plotted and near-perfectly executed vendetta springs from and unshakeable conviction in her husband's innocence. The seemingly loving nanny who plans to kill her charges may look like a western import but we have the Putana image to validate the fear of an evil mother who would poison the baby she suckles.

The director wants to make her an ambiguous anti-heroine whose vengeance springs from a perfectly valid Hindu virtue - blind faith in her husband - and yet hint at sexual straying to finally put her beyond the normal pale. Twice the film suggests that the demure governess (with severely braided hair and draped in simple saris) is attracted to the master of the house and fantasies about him. Before the character turns irredeemably evil, you see Anu Chastely enveloped in saris but when she turns killer, Anu Agarwal steps out of the pages of Vogue in black suit and red tie. From devious femininity, she transformed into androgynous killer. Tak creates a similar dress code for the third woman in the film. Varsha is a chain-smoking, flirtatious journalist always dressed in western clothes except for the infamous "choli" number where she plays the harlot of midriff-baring ethnic chic. No wonder she is easily dispensable and becomes the killer's first victim. Khalnayika might have flopped for the very obvious absence of a simpering romantic heroine the audience could fantasise about. The heroine has to be desirable, yes. But she must also be non-threatening and demure.

No one exemplifies this more than Juhi Chawla in Hum Hain Rahi Pyar Ke (1993). This charmingly juvenile remake of a more mature Hollywood hit mints the new bright image of the heroine as the nation's sweetheart. She must be an overgrown schoolgirl adorned with beribboned pigtails and dressed in pinafores. Of course, when the time comes she turns gutsy enough to fight for her man and put the scheming rich girl in her place. But for all her stubbornness and spunk in running away from home, Vyjayanti (Juhi Chawla) is Daddy's little cutiepie and the beloved of an equally sweetie pie male charmer. There is obviously no room for older and mature women. The trend is to go back to schoolgirlish giggles and gym slips.

Aaina pits the shy, congenitally self-sacrificing younger sister Reema (the forever sweet and submissive Juhi Chawla), against the ambitious, selfish and glamorous Roma (Amrita Singh, or imperious gal par excellence). Though it is the younger Reema who first sets eyes on the stylish tycoon Ravi (Jackie Shroff) and promptly falls in love, the hero naturally is besotted with the regally glacial Roma. Men don't fall in love with girls who wear glasses and moreover put oodles of oil in their long tresses! Roma is ambitious enough to run away from home to pursue a glamorous career in modelling and films on the eve of her wedding and the chagrined groom marries the docile Reema to keep up appearances. The script also hints that Ravi has all along admired the younger girl's patience, forgiving nature etc. etc. All the qualities desirable in a suitable, submissive wife.

The selfish big sister returns just when the hitherto platonic relationship is about to be consummated. After the devious tortures of deceit and misunderstandings, true love triumphs and the ambitious Roma comes to grief. Reema flaunts her Mangalsutra and the sanctity of Saat phera while Roma struts her sexual wares and seductive wiles. The script sketches in scenes of sibling rivalry dating back to schooldays and you hear the wise Dadima exhorting the mother to teach the elder one how to lose and the younger girl to fight for what is hers. But Aaina must need package this bit of pop psychology in the Pativrata norms of yore. Ambition in women is to be punished because even the most indulgent of fathers throw the prodigal daughter out.

Girls who warble on about the joys of the husband's home, 'Mari saari duniya hai tera angna,' are rewarded for their patience. Aaina was much lauded for its negative virtues- the absence of physical violence - but the condoning of psychic violence done to women went largely unnoticed. Meekness and patience are rewarded whereas the ambitious woman's attempt to exploit her sexuality for personal fame was condemned as morally reprehensible. The camera paid tribute to Juhi Chawla's demure charm while it played voyeur to Amrita Singh's aggressive sexuality, confident of its power. That power was shown to be manipulative even as the camera manipulated Amrita Singh's persona and milked it of every possible iota of titillation. Talk of paradoxes and double standards that rule commercial cinema!

The Woman's Gaze

Women filmmakers have sought to restore women's confidence and pride in their sexuality. Kalpana Lajmi's first film Ek Pal (1986) had conformed to textbook feminism, like Aparna Sen's Paroma (1985), to articulate a woman's right to her selfhood and sexuality. The protagonists in both films have extramarital affairs and both are made to announce a lack of guilt even though the filmic circumstance is to the contrary.

Lajmi's new film Rudali (1993) is a departure from feminist rhetoric which can be almost as tyrannical in its stereotyping as the old feminine variety. Lajmi brings and operatic flourish to a resonant narrative that details the arid life and dried up dreams of a Mother Courage figure. Sanichari's (Dimple Kapadia) life is so full of sorrows, betrayals and partings that she cannot cry ... even when she rejects the promised fulfilment of the unattainable love of her life. A deep commitment to her wastrel husband and vagabond son is as much a part of her psyche as is gritty sand part of the desert's harsh beauty. The son she so dotes on succumbs to his wanderlust and abandons her. It is the grief of losing the one friend, the visiting professional mourner, that burst the dam of Sanichari's grief. Poetic revenge lies in the fact that the dispossessed woman sells her tears to the feudal oppressors.

Lajmi contrasts two kinds of female sexuality - Rakhee's lush beauty and practised display of feminine wiles against Dimple's unadorned austerity that also hints at suppressed passion - to good effect. There is an underlying play on existential binaries - the lure of nomadic existence and the rootedness in one's own soil - and in a way, Rudali is a ballad that mourns the tragic outcome of these contrary impulses. Lajmi reveals that the woman who had abandoned home and child for the love of a wandering actor is the mother whom Sanichari knows only as a dear friend. It is wanderlust that takes away loved ones from a woman rooted in her own patch of soil. The poignancy of a barren earth mother runs like a lyrical undercurrent through Rudali.

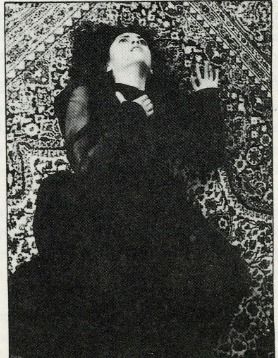

Illusion as in Maya

The point of Maya Memsaab is not to work at easy identification but to take Maya out of the mundane plane of existence all together. Death becomes her as does the passionate gratification of her rioting senses. The magical surrealism of Maya's death bestows a fabulous quality to a life lived with intensity. Is that freedom an existential mirage, an illusory chase after Maya? No other film has even dared to dream this philosophical vision and with such deliciously beautiful images and resonant words. You don't fully understand Maya. Nor can you forget her.

It is tempting to read in this illusory Maya an epitaph and an apostrophe to the essential mystery and unknowability of the Indian woman as she is sought to be captured in image and sound. Film is the shattered mirror of Maya in which a million fragmentary images collide and coalesce. Each fragment distorts the social reality out of which the imprisoned image seeks to escape. Escape where? Into yet another shard of splintered existence?

This essay was originally published in the book Frames Of Mind- Reflections Of Indian Cinema edited by Aruna Vasudev. The images used were taken from the original essay.

.jpg)