The Avenging Angels : Icons Of Death

Subscribe to read full article

This section is for paid subscribers only. Our subscription is only $37/- for one full year.

You get unlimited access to all paid section and features on the website with this subscription.

Not ready for a full subscription?

You can access this article for $2, and have it saved to your account for one year.

Commercial cinema has a way of subverting any new radical idea, to serve its box-office interests. Now, it seems to be the turn of feminism to fuel a desperate industry, fast running out of ideas and success formulas. Perhaps, this is too harsh an indictment and filmmakers have been sensitive to the growing articulation of feminists. The 'seventies were the angry decade of the anti-hero, marginalised women in the mainstream cinema, without freeing them from moral stereotypes as film noir did in Hollywood. The return of women-centred themes, first a trickle and now a flood, reflects the cultural schizophrenia of our society, the way it perceives and defines the role of women.

Mother India (1957) and the virtuous Sati Savitri (1957) have been with us and will continue to be with us until a cataclysmic revolution galvanises our thinking. These two images bolster up not only a feudal patriarchy, threatened by the inevitable atomisation of a society, moving towards industrialisation. Women too, confused by new choices and the absence of ready-role models, find in the old images a safe womb of certitudes. Martyrdom, specially when sanctified by religious approbation, is indeed seductive.

So, even in 1988, Ghar Ghar Ki Kahani /The Tale of Every Home), where the beautiful, beatific wife, named Sita, suffers unjust rejection by the husband, but continues to worshsip his photograph, to be commended by a so-called modern, professional women freezing in the emotional cold — is successful as Zakhmi Aurat /Wounded Woman sends a gang of rape victims on a castrating spree!

The first film is seductive though silly — and the second, unrepentantly sensational — and crude. Both speak about and through women. Even as this schizophrenia simmers along nicely to tease social scientists, there have been near-revolutionary changes from the early 'eighties. But these changes are couched in comfortingly familiar Hindu iconographic terms, intermittently energised by judicious imitations of foreign models from time to time.

The sanction of religious iconography was always there, ready to be tapped at propitious moments. The obverse of Mother India, the protective, nurturing Durga, has been the awesome destructive power of Kali. This Durga-Kali duality is in itself deeply ambivalent, celebratory and fearful of female power and female sexuality. When this duality is translated into the simplistic, unambiguous terms of the Hindi cinemas, the scenario gets murky and the intentions mindlessly exploitative.

Like most new trends, the beginnings were sounded out by the unapologetic B Graders. To Be Abroo /The Dishonoured (1983) and Bud Naseeb/The Unfortunate (1986) —classified as sexploiters-belongs to the dubious honour of ushering in the female avenger.

In Be Abroo, she is an investigative journalist, who turns into a female Jack the Ripper, methodically killing off the pimps of Bombay, because her own sister was a victim of one. Mission accomplished that is, within the finite limits set by the fantastic script — she jumps to her death, though there is a hero hovering in the background to honour her with his love.

Bud Naseeb pitted one intrepid girl against a killer, who systematically eliminates a fraternity of college friends for they might blow his cover of respectability. What is ominous is the way a bevy of girls are first titillatingly exposed and then punished for their sexuality. Oddly enough these crude and immensely successful films were the more respectable remakes from South Indian hits, which are far more legalistic in their theses. Mujhe Insaaf Chahiye/ I want Justice (1983) had an older women lawyer coming to the help of a middleclass girl, who is left pregnant by a rich boyfriend, turning tail at the idea of marriage. The twist was in how the young girl claims the right to name the man as the father of her child, but refuses to marry the now shamefaced, reformed rake.

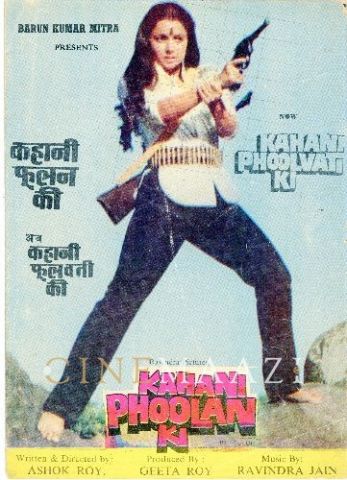

But the prevailing ethos of antiheroes taking the law into their hands since the system cannot deliver justice, was not conducive to such courtroom dramas. And, to middle-class defiance of convention. Around the same time, the saga of Phoolan Devi, the woman dacoit of Uttar Pradesh, whom the media built up as a combination of Mata Hari and glamorous gun-toter, wreaking vengeance on an unjust society, provided a readymade script for fly-by-night producers working on tight budgets.

Kahani Phoolan Ki /The Story of Phoolan (1985) and Putilibai were dutifully made and had moderate success. The actresses were not big names and the style followed the pseudo-Western path, which the male dacoit film had appropriated. The Indian horse-opera or the Curry Western, as it came to be called, operated within the parameters of rebels with a cause — and the titillation was provided by the mujra a more robust, yet poetic, indigenous version of the cabaret.

This new sub-genre operated within the same parameters and evolved its strictly observed conventions and wrote down its codes. Set in the hinterland of North India, with greedy landlords as satanic villains, the dispossessed or explotied victims operate within the same Thakur code of male honour, what applies to-the oppressors. The amazing complexity of the caste heirarchy is simpifled into the good Thakur versus the bad, while the personal suffering of protagonists is amplified to include all the oppressed.

.jpg/1%20(6)__340x480.jpg)

With female protagonists to the fore and played by the big star the avenger takes on the mantle of Kali. In a subversive way, this assertion of power and aggressive action by women is toned down to conform to mythology. The women working as independent entities, shorn of mythical trappings, would be more threatening to patriarchal values. Hence, we have the paradox of women being shorn of their femininity in order to play an active - and invariably tragic - role, and finally returning to feminine vulnerablity after the denouement.

Three films illustrate the working out of this new formula. Rape of either the protagonist or someone close to her is the final raison d'etre for forsaking passive femininity. Sitapur Ki Gita /Gita of Sitapur (1987) a none-too-subtle play on Hema Malini's blockbuster Sita Aur Gita (1972), in which she plays twins, (who are as different as can be) pits the heroine against a triumvirate of villains, who rape her almost immediately after she is married and kill her husband. Gita, who has been a chirpy village belle working as a servant to educate her darling younger brother, immediately picks up a gun and dons the new obligatory uniform leather-jacket, tight trousers, boots freed from the decorous braids of virginity.

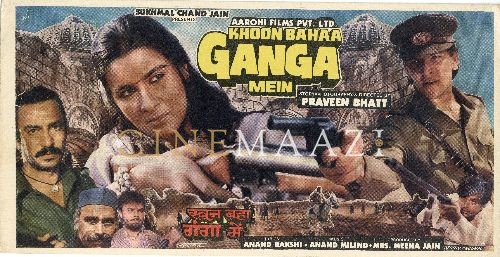

The older male, who becomes her mentor, is either the hither-to-absent father as in Sitapur Ki Gita — or an adoptive father figure, as in Khoon Baha Ganga Mein / Blood flows into the Ganga (1988). The protagonist has to battle two antagonists-the villainous Thakurs, masquerading under respectability and the police, usually a loved one sent to nab the outlaw.

In Sitapur Ki Gita, it is the younger brother, now a police inspector. In Khoon Baha Ganga Mein, it is the childhood sweetheart, whose father is the arch villain, having raped the heroine Ganga's (Amrita Singh's) mother and killed her father. Among all the many undistinguished films of this genre, Khoon Baha Ganga Mein is more sombre and nearer the psychological truth of a traumatised girl. The heroine switches over to a dhoti and speaks the same rural patois, unlike in other films, where a more standardised Hindi takes over for wider appeal.

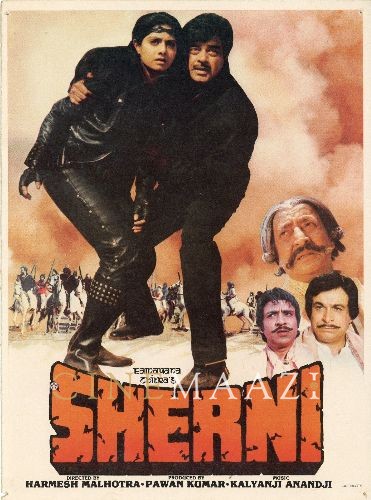

The third film, starring current superstar Sridevi, is Sherni (1988), which again faithfully adheres to the formula of a sprightly village girl joining her dacoit father, when her mother and young siblings are massacred and she herself escapes repeatedly from molestation. Sherni endows its heroine, Durga, with a social conscience, so that she also fights against perpetrators of dowry deaths. The tragedy of Durga is that she is forced to take up a gun, when earlier, she had passionately argued with her unjustly imprisoned father that the law would finally redress the wrong done to him.

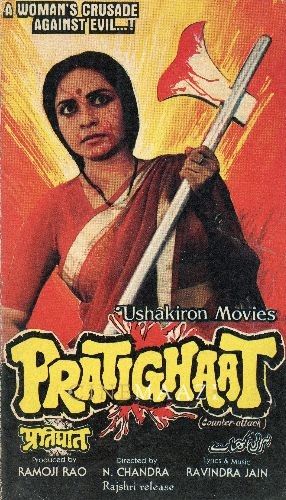

The other phenomenon that has surfaced in Pratighat / Resistance (1987), Mera Shikar / My Prey (1988) and Zakhmi Aurat is that women don't turn into outlaws, but are finally driven to catclysmic violence. The corrupt system symbolised by one great villain is too pervasive, too entrenched and it emasculates most men. This thesis finds its most elaborate exposition in Pratighat, remade from a Telugu hit. Lakshmi (Sujata Mehta) is a college lecturer who, on coming to a small town, is appalled by the tyrant's rule that goes unquestioned by everyone, inlcuding her lawyer husband. For her act of defiance, reporting to the police against the thug she is disrobed in broad daylight under the shocked, but helpless gaze of the public, which includes her husband.

This notoriety makes Lakshmi the target of insult and her male students ask her to graphically explain an erotic passage in class. Lakshmi's answer, accompanied by a song that hits the high notes aurally and visually, is to draw a nude woman nursing her child. The shamed students accepts her their unquestioned leader and surrogate Mother-figure. Determined to fight the thug, who now seeks the legitimacy of an elected office, Lakshmi beheads him publicly with an axe, since the elections are rigged. Prior to this, she leaves her cowardly husband and also aborts her unborn child not to assert her right over her body, but to be free to act in a masculine world.

In essence, she has to destroy her femininity- the Mother image, with which she had earlier identified — and wield the axe, mythologically the awesome weapone of Parasurama, who rid the world of the warrior class to avenge his mother's dishonour. Lakshmi's iconic stance recalls Kali, but the weapon is masculine. Though crudely made, Pratighat went on to become the biggest hit of 1987.

.jpg/1%20(4)__382x480.jpg)

Zakhmi Aurat makes its Police Inspector heroine Kiran (Dimple Kapadia) the victim of sadistic gang-rape, after lovingly showing her in the male accoutrements of office — powerful bike, gun, and khaki uniform. She is hardly ever shown in a sari. When she is raped, the film uses the recurring image of her jeans hanging from the ceiling in a spirit of punishing her for daring to do man's job. It is her boyfriend, who gives her the modern equivalent of the Gitopadesh. Kiran becomes the leader of a gang of castrators in the guise of a female Arjuna, battling with her enemies. The events after the rape are not only absurd and crude, but filled with enough obscence titillation in the guise of a song-and-dance number, ostensibly intended to humiliate a castrated rapist to give the exploitative game away.

It is Dimple once again in the latest Mera Shikar, transformed from a chatty village girl driving a tonga into a one-woman armoured battalion, when a dreaded dacoit rapes her sister in public after she is married. The newly-weds die and Bijli takes a crash course in karate, boxing, fencing, riding from a city martial-arts expert. Even as the film begins, Bijli dreams of donning leather boots and trousers, jumping off cliffs to subdue a gang of thugs, who would,kidnap a girl. Mera Shikar is pure camp and her do-or-die struggle is against a samurai-like antagonist, with a flowing top knot and slit eyes, who relishes the one-to-one challenge.

As if this deluge was not enough, more films are under production starring Dimple Kapadia, Hema Malini and Rekha, besides younger actressess all bent upon a superficial masculinisation of the female protagonist. On the prevailing evidence, the heroine will also have to periodically resort to feminine guile in the form of mujras and be both a seductress and an avenger. It is not that our film industry is moving towards some sort of an androgynous ideal. There is enough indication of hostility towards an aggressive woman in the temporal world of power. Women power is acceptable only when it is mythologised — and the women is made a mere icon, an Avenging Angel, a dispenser of death.

The article was originally published in the Indian Cinema (1988). The images used in the feature are taken from the original article and Cinemaazi archive.

.jpg)