Shobi Je Tomari Gaan: The Music of Ajay Das

Subscribe to read full article

This section is for paid subscribers only. Our subscription is only $37/- for one full year.

You get unlimited access to all paid section and features on the website with this subscription.

Not ready for a full subscription?

You can access this article for $2, and have it saved to your account for one year.

Prologue

April 2013. The composer lay on the bed. A sudden ailment had immobilized him. Multiple-organ failure, the doctors said. Forget song sittings, even daily visits to the local tea stall were prohibited.

Despite his predicament, his zest for life had not taken a dip. He used to call his friends, fellow musicians and lyricists, often joking that they had become too big for him. One among them was lyricist Manojit Goswami, who had come from Halisahar, some 70 km away, to finalise a song for the film Gublu.

Against the wishes of both his wife and Manojit, the composer had to be taken to the living room. The mukhda of the song had been written during the previous sitting. He started composing on the harmonium, giving Manojit multiple options for the antaras. The song was completed in a matter of minutes. The composer’s wife did the first-cut recording which had to be sent to Asha Bhosle as per the composer’s wishes.

Unfortunately, the composer was oblivious to all that went on after he was through with the song. He had to be transferred to a hospital soon…

The story

Srinath Das was a distinguished barrister at the Calcutta High Court in the nineteenth century, and one of the first to sign Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar’s petition for widow remarriage. A resident of Bowbazar in North Calcutta, today the road parallel to Jadunath Dey Road off Nirmal Chandra Street is named after him.

Two generations down the line, a certain Phanindra Nath Das, a grandnephew of Srinath Das, would inherit several businesses including a cinema hall at Nabadwip, north of Calcutta. Phanindra Nath was married to Amiya Das, whose musical sensibilities were above average. The Das family had an organ, and Amiya Das was the chosen one to play the same during social occasions. She also composed a few songs that found appreciation within the inner circle. The couple had three sons and two daughters.

Ajayendra Nath (Ajay), the second son, was the third offspring, who, as per his family, was born on 22 January 1941.

By the time Ajay joined college, Sukhen, under the watchful eyes of Debaki Bose and Deb Narayan Gupta, was a sought-after child/character actor in Bengali cinema. However, cinema did not hold any interest for Ajay. He took after his mother and was into writing and composing from the age of fourteen. His elder brother Malay was a member of the Congress party. Ajay, on the other hand, was fascinated by the leadership and oratory skills of Ashim Chatterjee (aka Kaka), the firebrand Naxalite activist, and his followers like Saibal Mitra. Idealism triggered the rebel in him. Unfortunately, rebels too needed money to survive, something that forced Ajay to support himself through music tuitions, which brought in an income of Rs 30 per month. However, to the amusement of friends and family, Ajay started donating the entire amount to the CPI(M).

Sukh naame sukh pakhi

Dukher i naam sari

Sujan amar holo na sukh

Dukkhyo amari

Shibdas Banerjee would later alter the lyrics as per the demands of the film. Jemon Shri Radha kande, sung by Shyamal Mitra for Panna Heere Chuni (1969), found Ajay Das recording his first composition for films.

The music arrangement of Panna Heere Chuni was by Y.S. Mulki. Apart from being an arranger, Mulki was also one of the most well-known accordion players in the country. His expertise on the nuances of music impressed many, and the list had one more name in 1969. Ajay Das. He later considered Mulki the best arranger he had worked with. Incidentally, Mulki’s musical proficiency, razor-sharp memory, and down-to-earth nature were reasons stalwarts had no issues in acknowledging his greatness. One among the lot was Manna Dey, with whom Ajay was eager to work, something they did together first for the song Anek din kete gelo from Achena Atithi (1973). Their partnership resulted in many hits, of which Bharat amar bharat barsho (Charmurti, 1978) has an interesting history.

Sarbani Das goes back in time: ‘Director Umanath Bhattacharya, considering the period nature of the film, wanted Tenida, the lead character (played by Chinmoy Roy), to sing a Dwijendra Geeti (song written and composed by D.L. Roy, 1863-1913). Ajay requested he be given the liberty to create a song that would sound like a Dwijendra Geeti. After hearing Bharat amar bharat barsho, Bhattacharya was confused; he thought it was a Dwijendra Geeti. Part credit goes to Shibdas Banerjee as well, his lyric sounds like a Swadeshi poem of pre-Independent India. With time, the song became so popular that many schools unknowingly thought it was a Dwijendra Geeti and used it like a prayer during the assembly session.’

By this time, Ajay too had reached a position of eminence, in the sense that he could dictate what he wanted. The song was planned for Manna Dey with the chorus joining him. After the recording was over, Ajay walked to Manna Dey, requesting him for another take, this time a solo version. Intrigued, Manna obliged, nevertheless. That version was finally used in the film.

Rubbing shoulders with a group that had strong socio-political connections was instrumental in shaping Ajay’s thoughts as well. For example, he knew exactly what a Dwijendra Geeti needed to sound like. This quality had probably taken a quantum leap during the early 1970s, when he was composing for a film titled Palabar Path Nei. Directed by rookie Amitava Bhattacharya and starring Subhendu Chatterjee and Aparna Sen in the lead, this film and its music never saw the light of the day. However, it had some remarkable songs, of which two – Hey mahamanab and Matha tolo tumi Bindhyachal – were set to the poetry of Sukanta Bhattacharya and sung by Hemanta Mukherjee. The former used a complex structure, where the forms kept changing between stanzas. The latter sounded like a hymn; one can find a private recording on YouTube.

Ami thikaana biheen pothe amar thikaana jenechhi

Antabiheen shey poth dhore cholechhi sudhu cholechhi

Ami hazaar raater andhokare thamini

Koto herechhi tobuo haraar byatha ke manini

Later, when the CPI(M) was in power, Salil Chowdhury tried to get the songs published from HMV. He also knocked at the doors of Buddhadev Bhattacharya, then minister of information and cultural affairs, who is also Sukanta’s nephew. But not much could be done. Ajay’s compositions, an embodiment of the struggle and despair he had been through in the 1960s, never saw the light of the day.

The Bangladesh liberation movement was a fertile ground for filmmakers in the early 1970s. As it was for Sudhir Saha, who was producing Archana (1971). The singers signed for the film were mostly veterans – Hemanta Mukherjee, Shyamal Mitra and Mrinal Chakraborty. The title song – which served as the critical link in the film and had to be sung twice, one with full instrumentation and the other with minimum – mandated a well-known female voice. Saha would have none but Arati Mukherji, who incidentally was preoccupied with other recordings. Ajay suggested Banashree Sengupta. Saha was reluctant. Ajay put his film career on the line. Door akashe tomaar sur, the title song, which was eventually sung by Banashree, became a monumental hit; no function of her would be complete without that. Archana had a modest run too, propelled by the extraordinary popularity of the song. For the interested, the sarangi prelude to the song, based on Raag Puriya Dhanashree, probably served as an inspiration to composers Laxmikant and Pyarelal for Mere saanso se jo mehek aa rahi hai (Badalte Rishte, 1978).

Geeta Dey, infamous for portraying the wicked aunt or mother-in-law, had a small role in Archana. An extremely soft and helpful human being in real life, she had a fondness for Ajay. Using her influence, she managed a job for him in one of the most prestigious institutions, the State Bank of India. Ajay, still driven by altruistic intentions and blinkered visions about life, chose to resign after two months. His decision to pursue music, and only music, was probably the calling of his heart, but one wonders what could have happened if he had carried on with the job. SBI, apart from lending financial stability, also gave a lot of flexibility to its employees. For example, Chuni Goswami, arguably the best footballer India ever had – and the poster boy of Mohan Bagan club – also worked for SBI.

Incidentally, Goswami was probably one of the reasons Ajay was a diehard supporter of Mohan Bagan. He had a brown panjabi (a form of kurta special to Bengal) which he used to wear whenever he went to see Mohan Bagan–East Bengal matches; he considered it lucky.

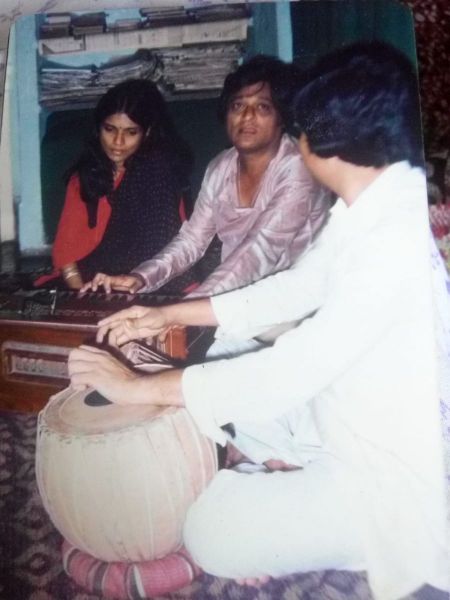

Around 1973, Ajay, at the invitation of Salil Chowdhury, met a group of music enthusiasts at Mallickpur, a suburb adjacent to Baruipur in South 24 Paraganas, to discuss music for the poetry of Sukanta Bhattacharya. One among the musically inclined was Sarbani Bandyopadhyay, daughter of Amiya Bhattacharya of the IPTA. Amiya Bhattacharya, among many other things, was known in the circuit for dramatizing, in the form of a Geeti Natya, the song Shei meye, composed by Salil Chowdhury and sung by Suchitra Mitra. Sarbani had completed her master’s in International Relations from Jadavpur University in 1972 and was working in the administration department of Sarabhai Chemicals. Ajay and Sarbani got married on 6 June 1975. By that time, Ajay had moved to a Library apartment of Srinath Das in Bowbazar area. One of the rooms was partitioned for Ajay and his newly married wife. Their only child Shayeri was born there, on 7 May 1977. After a few years, the family moved to Manohar Pukur Road in south Calcutta.

Ajay’s piano, rented from H. Paul and Co. was one of the artefacts which moved with him to his new house. Along with the harmonium, piano was an instrument after his heart. Paul and Co., whose customers included stalwarts like Hemanta Mukherjee and V. Balsara, also had an AMC with Ajay, and they provided service as part of the contract and on demand.

The success he had with Subhendu’s voice also bolstered the argument that voices need not be perfect in a film song. He was particularly in favour of using the voices of actors when there was an opportunity. Apart from Subhendu, he made Chinmoy Roy and Robi Ghosh do their own playback in the duet Tumi raja moder raja praner raja bhai in Ghosh’s film Sadhu Judhistirer Karcha (1974). While Chinmoy had some musical genes in his body, Ghosh had a singing voice bordering on the disastrous. Given the comic grain of the film, the experiment worked. He also made Shakuntala Barua playback for Arati Bhattacharya – in a falsetto to suit the actress – in Nyay Anyay (1981), when Ms Barua had decided to temporarily give up acting.

Life at Manohar Pukur Road was hectic, even by Ajay’s standards. For one, he was getting multiple film assignments. He would be preoccupied with composing songs almost every day. A chain smoker whose favourite brand was Gold Flake, his evenings would be spent with the harmonium placed on the carpet in the living room. And quite often, he would fall asleep there.

The story of Ajay’s abortive attempts to meet Kishore Kumar have been recounted by lyricist Pulak Bandyopadhyay and interested readers may refer to Bandyopadhyay’s autobiography Kathaye Kathaye Raat Hoye Jaye. To surmise what has been documented, Ajay and Sukhen were swindled and made to wait for a few weeks in a Bombay hotel to get Kishore Kumar’s date without the singer having a clue about the same.

The introduction with Kishore Kumar happened at Bombay Labs. By that time, Kishore had received the cassette with the song and had prepared himself thoroughly for the take. At the studio, he requested Sukhen to describe the sequence in detail. Next, he asked Ajay to sing the song, which was to be recorded that day, in case there was a need to alter some tune or expression. He then sat down on his trademark chair and did a voice test. Till the time Kishore instructed Uttam Singh, who was arranging the tune, and recordist B.N. Sharma for the final take, Ajay was in a trance. For him it was a dream he had never dared to dream. Hoy toh amake karo mone nei for Pratishod (1981), though not very aesthetically shot – in fact the picturization has been the butt of jokes for the last four decades – remains hugely popular for the simple tune and Kishore’s full-throated singing.

The journey which started with Kishore Kumar in 1981 continued till Kishore’s last days. They collaborated on twelve films and for twenty songs, out of which eighteen were solos. This is the highest number of Bengali film songs Kishore Kumar sang for a Calcutta-based composer. Ajay also made Kishore sing tandem songs with both the Mangeshi sisters, Lata: Ami je ke tomaar (Anurager Chhowa, 1986); and Asha: Amar e kantha bhore, (Jibon Moron, 1983) and Bhalobasha chhara aar ache ki (Paap Punyo, 1987).

The unexpected death of Kishore Kumar was a huge blow to Ajay. Like many, especially R.D. Burman, he too would compose with Kishore in mind. Now that Kishore was no more, he found it difficult to make his magic work. This could be a reason why his songs in the 1990s and the millennium did not have the spark that characterized his earlier work.

Ajay was, however, prolific. His output extended to basic songs and the radio as well. Almost all leading artistes of that time – including ones not connected with Bengali music like Vani Jairam and Anuradha Paudwal – sang for him.

His command over creating melodies based on Hindustani classical music has never been discussed seriously. Prominent semi-classical songs composed by Ajay would include the Raag Sankara-based Bandite cheona amaye, sung by Mrinal Chakrabarty and Sipra Basu in Maan Abhimaan (1978). But Ajay did not limit himself to conventional raags. His repertoire also finds the use of Raag Chandranandan for Raat amar shudhu je geche kandiye, a non-film song by Arati Mukherji. Chandranandan, pioneers of classical music will recall, is a relatively new raag, created by Ustad Ali Akbar Khan.

Among the more popular ones, it is impossible to miss the mysterious tenor generated by the mix of chromatic notes in the otherwise pentatonic Shivranjani-based song Amar e kantha bhore (Kishore/Asha, Jibon Moron), something R.D. Burman also did successfully in the song Mere naina saawan bhadon (Mehbooba, 1976).

However, one category of people Ajay failed to manage were film producers. Probably part of his father’s complete lack of business sense rubbed off on his son as well. His simplicity and submissiveness were also taken advantage of at times. For example, in 1969, HMV officials asked him to deliver albums of Panna Heere Chuni to a few music stores, despite the fact that he was the music director of the hit film and deserved better treatment. There were also instances when he was made to accept less renumeration for his work. The struggle with finances carried on till his last days, even when he had shifted to a flat at Patuli near Garia, Calcutta.

There is a proverb in Bengali – Gneyo jogi bheekh paye na, which roughly translates to ‘the country minstrel gets no alms.’ If there was one person the proverb applied to well, it was Ajay. Despite cornering a major share of the Bengali film music market in the 1980s, his was a name carefully avoided by scribes, music critics and the ruling dispensation. He was never associated with the top directors of his time. No Satyajit Ray, Mrinal Sen, Ritwik Ghatak or Tapan Sinha for him. Not even Ajoy Kar, Dinen Gupta, Arabinda Mukherjee, Rajen Tarafdar, Asit Sen, or Pijush Basu. His only association with Tarun Majumdar was as one of the many composers for a film made when Majumdar was no longer in his prime, Sajani Go Sajani (1991).

His life revolved around two things – music and friends. He was seldom seen at parties where champagne flowed. Or where green tea was served to people discussing aesthetics with Bach and Beethoven playing in the background. He could jolly well pass off as the common man lost in his thoughts, drinking countless cups of tea at Maharani, a stall he used to frequent, and humming a tune he was composing.

Courtesy Subhendu, who was an orthopaedic doctor by education, Ajay had many doctor friends, and consequently, he was part of the doctor’s association that held musical soirees on the first floor of the building that housed the United Bank of India, Lansdowne branch in Bhowanipore, south Calcutta. Ajay’s mixed puffed rice was something everybody looked forward to and was considered a delicacy. He was more at home having muri and tea in a close-knit group than at five-star dinners.

Epilogue

In June 2013, Manojit carried the cassette to Bombay. A misty-eyed Asha Bhosle recorded Prem bhora dui chokhe at Geet Audiocraft, Andheri West, Bombay, the last composition of Ajay Das. The world had come a full circle. She was the first Bombay-based singer to sing his film song. And, incidentally, the last too.

One of the many compositions of Ajay which unfortunately we never got to hear…

Notes

1. The chronicled date of birth of Ajay’s younger brother Sukhen is 28 July 1938. Hence, both the dates are under the scanner as Ajay was elder to Sukhen by a year & a half

2. Pan India viewers would remember Samjhauta , a musical hit of 1973. It was based on Panna Heere Chuni , Sukhen wsa credited as the story writer.

3. A tandem song is when the same song has two versions – mostly a male version and a female version. This term was coined for Hindi film songs by veteran journalist, the late Raju Bharatan.

Acknowledgements

• Sarbani Das and Shayeri Das, wife and daughter of late Ajay Das, without whom the feature would not have been possible

• Another pair of mother and daughter, Shakuntala Barua and Rajoshi Vidyarthi, who helped with interviews and in connecting with the family members of Ajay Das

• Manojit Goswami, lyricist, composer and arranger in the Bengal film industry

• Manjari Banerjee, Brisbane-based music lover who was a student of Ajay Das

• Archisman Mozumder, Bombay-based Hindustani classical aficionado and researcher

• Sarbajit Mitra, London-based PhD scholar

• Somnath Ganguly, Hong Kong-based music aficionado

• Subhash R. Ghosh, UK-based music lover

• Abir Bhattacharya , Mithun Pal, Indranil Mukherjee & Arnab Banerjee, Calcutta based film aficionado

Tags

About the Author

Anirudha Bhattacharjee is an alumnus of IIT Kharagpur who works as an SAP consultant. He divides his time between work, family, singing, solving puzzles, quizzing, and watching football or films of Wilder, Hitchcock, Satyajit Ray and anything that has the semblance of a biopic/comedy/noir/alternative history. A writer by accident, his area of interest is mainly Hindi and Bengali cinema between 1950 and 1985. He is the co-author of the National award-winning book R.D. Burman: The Man, The Music, the MAMI winner Gaata Rahe Mera Dil and the critically acclaimed S.D. Burman: The Prince-Musician. Anirudha stays in Bangalore with his wife Sudipta and sons Aritra and Shaunak, all of whom share his passion for cinema.

.jpg)