Problems Facing The Film Industry

Fourteen years have passed since India became free. During his period the motion picture has grown in popular esteem and become the nation's foremost entertainer. More people than ever see films today, though unfortunately compared with the rising population and standard of living, the cinema houses in India are too few in number to meet our needs. To be precise, there are just four thousand theatres to cater for forty crores of people!

The film industry is faced with a paradoxical situation today. On the one hand, the cinema house with their long queues and house-full boards present a picture of prosperity; on the other, the studios, some of which have been converted into factories, provide a dismal picture of crisis, insecurity and slump. That there is a slump and a crisis in film production there is no doubt. Several factors have contributed to this unpleasant state of affairs- viz., lack of finance, lack of buyers, the star system, the Censor and the picture goers' attitude.

It is wrong to blame Censors alone for our present predicament. In fact, the lack of finance is the main cause of the current slump. Indeed, the entire financing system is faulty in the film industry. Before the war, the film studios did not hire out their studios to independent producers, but produced their own pictures on advances given by distributors. These studios had their own permanent staff of technicians, musicians and artists. During the war, with the licence system, came the speculator financier who advanced the black money he made to independent producers, who, in turn, paid the black money to the stars.

The film industry is often condemned for indulging in the payment of black money. But it is forgotten that neither the producer nor the movie artiste was aware of black money until the wartime merchant, who had a lot of it to invest in the film trade, initiated them into it. And this financier has ever since been dictating to the producer what kind of pictures to make and which artistes to sign.

The financiers and the distributors are thus jointly responsible for the evils of black money and the star system. And the producer unless he happens to be an obstinate individual like me, has not been able to defy this evil. As for myself, right from the beginning, I have been able to make pictures without stars. And even when all other producers advised me to go in for stars, I was able to resist the temptation of falling prey to this common weakness, thus managing to steer clear of the evils of the star system.

The usurious rate of interest charged by the financier and the exorbitant prices demanded by the stars were bound to create a crisis when the film flopped or could not secure a buyer. Well, the major crisis today stems from the fact that the cost of production is not consistent with the guarantees offered by the distributors. What is worse, due to none-completion of several pictures in which crores of rupees have been invested, the distributors are unable to make fresh commitments. Result: the financiers, too, have become shy and are not willing to lend their support to any new project.

This state of affairs is not likely to improve unless finance is available on reasonable terms and conditions. All over the world, the banks advance money for film production, but, in India, it is only the speculator financier who advances money to the film producer. The bankers and the industrialists appear to nurse a conservative prejudice against the film industry. Otherwise, they would have come forward at least to build a chain of theatres, thereby taking advantage of the boom in the exhibition trade. I have had a quite bitter experience of this traditional distrust on the part of the banking corporation where show business is concerned.

The film finance corporation could replace the speculator financier and thus help to producers to meet the crisis. But its resources appear to be too meagre and its working too slow to help the entire industry to tide over the critics. And yet, gradually it could play an effective role not only in helping industry to face the financial crises, but also in mitigating the twin evils of the star system and black money.

The Censors, too, have contributed a lot to precipitating the crisis. In this connection, I would at the outset like to make it clear that the film producers are not against censorship as such President Rajendrea Prasad is reported to have said that the producers were opposed to the censoring of films. I can assure him that I know of no producer who seeks the licence to make pictures without being subjected to censorship. Time and again, the producers through their representatives have made it clear that they are not at all against censorship; nor do they defend vulgarity or obscenity in films. Personally, I feel that, from the viewpoint of the producers who want to make good and decent pictures, censorship is desirable.

Similarly, there is nothing essentially wrong with the Censor Code. What is needed is an intelligent, liberal, uniform and rational interpretation of the Code. The Censors should guide the producers, rather than just sit in judgment on them, for only that way can they be of real help to them. Today, censorship has become an ordeal, with the producer's fate at the mercy of the Censors' whimsical and arbitrary interpretation of the Code.

In the old day, the Censors were more concerned with politics than morality. In 1930, I had to change the title of a film from SwarajyaToran to UdayKal to satisfy the foreign Censors. With the advent of freedom, there was a natural shift towards puritanism. In their zeal to preserve our ancient traditions and culture, the Censors became increasingly puritanical and moralistic in their outlook. However, one expected that, with the passage of time, this zeal would die away, just as the prejudices against the British have died away.

But the Censors have not been able to keep pace with changing social conditions and manners. I, for one, would not plead for licence to show anything obscene or vulgar: but, at the same time, I would call upon the Censors to be more rational and uniform in judging films.

In this connection, I am surprised that no less a person than Dr Keskar has justified the double standard applied in certifying foreign and Indian films. True, Western manners differ to some extent, a wedding kiss or a farewell kiss is quite understandable, but a passionate kiss in public is not common Western practice; nor is semi-nudity. Indeed, four years ago, when I went to the U.S.A., I had the opportunity to point out so some Americans the difference between the life I saw there and the life presented in Hollywood pictures. They averred that the life depicted in a majority of their movies was only to be found in the nightclubs of America. Surely, the fact that the customs and way of life of the West are different does not in any way justify the Censors' lenient attitude in allowing semi-nudity and passionate love scenes in foreign films.

This attitude of the Censors has affected Indian films rather adversely. As a result, during the last three years, the business done by foreign films in India has gone up beyond expectations. Recently, a foreign film was revived at a leading Indian cinema house in Bombay and it did record business, surpassing the collections of all Indian pictures screened there! And this foreign film, which depicted the crime story of a wife double-crossing her husband, had nothing but semi-nudity and passionate love scenes to commend it.

Apart from the undue advantage given to foreign film by the application of a double standard, this is something basically wrong. For the purport of censorship is to protect the spectator from evil moral influence. And as the foreign, as well as the Indian films, are seen by Indians,it is wrong to judge the two by different yardsticks. Or is it presumed that Marilyn Monroe's passionate love scenes and semi-nudity have not baneful influence on the audience, while those of an Indian actress has such an influence? This attitude of the Censors could well induce an Indian producer to make a picture with a foreign locale and foreign characters in an attempt to take advantage of the double-morality code applied by the Censors.

Thus the arbitrary interpretation of the Code and the lack of a rational outlook among the Censors have created a number of difficulties in the way of even those producers who want to make good and decent films.

The Censors, as I have said are not inclined to keep abreast of changing social conditions in India, and are applying outmoded puritanical yardsticks in imposing the Code on Indian films. But the present crisis is also partly due to our producers' inability to keep track of the ever-changing taste of the audience. The commercial film producers invariably cater simply to the public taste; but the producer with real artistic vision strives to improve upon this and gives pure aesthetic pleasure to the audience. It is his duty to foster a taste for art and a respect for the right human values. Of course, in doing so, if he tries to be too abstract and individualistic, discarding popular form and ignoring the general level of audience intelligence, there is the danger of his work's turning out to be a complete flop.

In the beginning I, too, had to make action pictures. In those days, a hero was a superman who successfully fought against fifty men at a time. I tried to make these fights more realistic by effecting a reduction in the number of opponents and providing a human cause for the fight. Thus, by keeping a little ahead of the public demand, I have been successful, in my three decades of film-making, in producing purposeful and artistic and at the same time popular pictures.

This synthesis of what the public wants and what the public needs has been the secret of my success. The producers who cater to public taste at the expense of art and accepted moral values are doing a great disservice to the film industry an inviting the wrath of the Censors and the moralists. The producer who deals with abstract art without caring for public demand also lives in an ivory tower without any practical outlook. For, after all, there can be no justification for making motion pictures which the public just will not see.

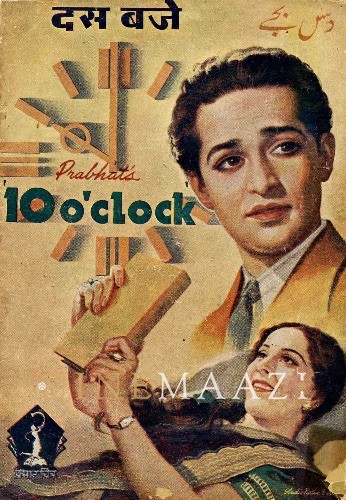

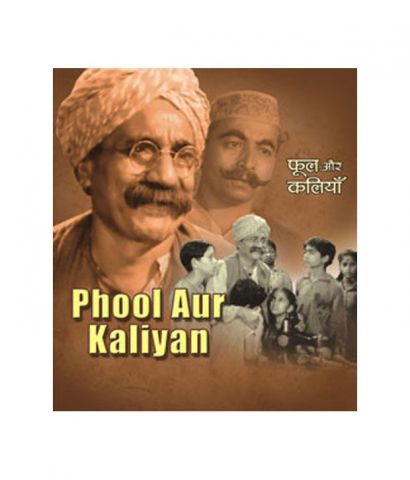

That is how I felt after making an award-winning children's film in Phool Aur Kaliyan (1960). For a long time now, it has been said that our children need films specially made for them. As an experienced producer, I felt it to be my duty to help the children's film movement by making a children's film on my own. And I felt greatly rewarded in my endeavour when Phool Aur Kaliyan won the Prime Minister's Gold Medal. But, when I released the picture in Bombay, to my dismay I found that neither the children nor their parents were interested in seeing it. Or rather, since the parents were not interested, they did not take their children to this children's film. Even the school authorities, the Education Department and the Government, who always clamour for children's films, evinced no interest in the picture. If after this better experience a producer like me feels that the production of children's films is a waste of hard-earned money, since no one is interested in making the children's film, will be wrong.

Of course, there are producers who are neither discouraged by such antipathy nor disheartened by obnoxious criticism, since they have complete faith in their audience. For, after all, it is his faith in ultimate goodwill and support of the picturegoer that gives a producer the strength to fight against all odds-finance, the Censors, taxation, the star system, the Government's antipathy and numerous other difficulties. For thirty years now, I have thriven on that goodwill and support, and I have no doubt that I will continue to gain them in the future, too.

This article was originally published in Film Industry of India, compilled by B K Adarsh in 1963. The images used were not part of the original article.

Tags

About the Author

.jpg)