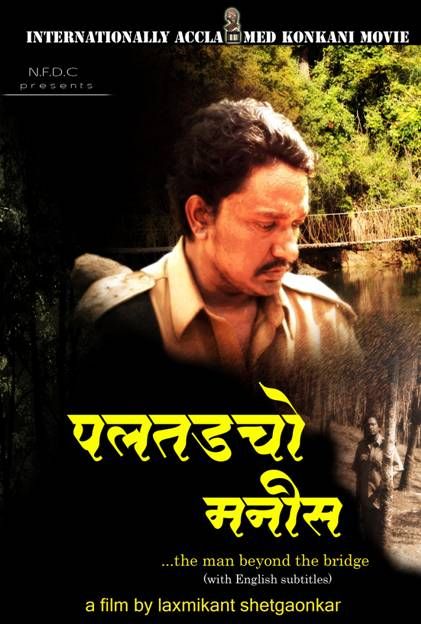

Paltadacho Munis and the Coming of Age of Konkani Cinema

Subscribe to read full article

This section is for paid subscribers only. Our subscription is only $37/- for one full year.

You get unlimited access to all paid section and features on the website with this subscription.

Not ready for a full subscription?

You can access this article for $2, and have it saved to your account for one year.

Laxmikant Shetgaonkar’s debut feature received the FIPRESCI Prize for Discovery at the 2009 Toronto International Film Festival. It weaves in issues of mental health, the environment and power structures that operate in the Indian hinterland, and provided a much-needed boost to Konkani cinema.

For a debut feature in a language that is largely unheralded in Indian cinema, it was indeed high praise. In its citation, the Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF) said, ‘Far from the sensory overload of India’s big cities, this film explores smaller but enduring dilemmas, drawing together keen environmental sensitivity with a nuanced view of village dynamics. Director Shetgaonkar, immersed in the culture of the region, tells his tale with grace and attentiveness, taking the villages traditions and beliefs seriously, while casting a jaundiced eye on those who exploit them.’

The director, Laxmikant Shetgaonkar, was born in Goa. A graduate in theatre arts with a diploma computer applications, he worked as an actor-teacher in the National School of Drama in New Delhi and conducted many acting workshops across India. He also designed and directed several theatre productions like Hara Samandar and Karnabharam.

He worked as a screenplay writer and assistant director on several TV and film projects before starting independently. Before directing Paltadacho Munis, he made the Konkani-English documentary on HIV, Let’s Talk About It (2005). His Marathi documentary Eka Sagar Kinara (2005) was shown at the Mumbai International Film Festival and bagged the Golden Conch. His other non-feature films include the Konkani-English documentary Can You Hear My Silence (2007), on the origin and growth of sex trade in Vasco; Tales of Ganges, on the widows of Varanasi; and Navjawan, a probing look at the psyche of youngsters from small towns studying in urban colleges. For his outstanding achievement in building film culture in Goa, he was felicitated by the Goa government in 2009.

The novel and the film differ in many ways, with the director adding is own creative take. In the novel, the woman (who discloses her name as Mitra) recovers her mental balance, whereas in the film she does not. The novel explains the reasons that led her to lose her faculties, and deals at length with her past and her family and that of the death of Vinayak’s wife. In the film, the woman does not talk about her past. She does not visit her family. The film makes a passing reference to the death of Vinayak’s wife, Uma. The director brings in the construction of a temple, this adding a touch of contemporaneity to the film. A politician enters the picture as the village headman. He wants to build the temple in the forest, unscrupulously using the forest and its trees for the construction. The headman gets elected with a thumping majority riding on the emotions roused by the construction of the temple.

The cinematography beautifully captures the scenic splendour of the Western Ghats, its verdant greenery, its flora and fauna. The film was extensively shot in Gokuldem, Paddi, Subdolem, Morpirla and Cotigao sanctuary. The scene depicting the rope bridge was shot on Gokuldem river. The chirping of birds, the echoes of the jungle and the sound of the running water, the wood being sawed add verisimilitude to the film. Similarly, the blowing of the bugles, beating of the drums during the procession of the temple with the background music create a beautiful spectacle.

The director deserves kudos for the final scene where Vinayak is shown snapping the rope bridge, depicting that no civilized society should interfere in the life of the villagers. The woman has at last escaped human depredations to attain a measure of independence.

In its subtle and unsentimental exploration of contemporary themes, its performances and in realistically highlighting the dialects of the Konkani language in the furtherance of its narrative, Paltadacho Munis is an important contribution to the many cinemas of India.

Producer: National Film Development Corporation of India

Story: Mahabaleshwar Sail

Screenplay & direction: Laxmikant Shetgaonkar

D.O.P: Arup Mandal

Editor: Sankalp Meshram

Sound: Rajiv Hegde

Music: Ved Nair

Executive Producer: Entertainment Network of Goa

Cast: Chittaranjan Giri, Vasant Josalkar, Prashanti Talpankar, Veena Jamkar

Awards & Festivals

• FIPRESCI Award at Toronto International film Festival ’09

• Hong Kong Asian Film Festival ’09

• Cairo International Film Festival ’09

• Mumbai Film Festival ’09

• International Film Festival of India ’09

• 3rd Eye International Film Festival Mumbai ’09

• Palm Springs International Film Festival ’10

• Pune International Film Festival ’10

• Berlin International Film Festival ’10

Tags

About the Author

Isidore Dantas self learnt Konkani after leaving Goa at the age of 13 and resettling in Mumbai/Pune.

After scanning newspapers, pot boiler novels and anything written in Konkani, he has managed to pick up enough of the language to have penned a book on Konkani films in all its three major scripts, authored a biography of an artist Alfred Rose, penned a history of Goan journals and newspapers, published an English Konkani dictionary and acted as a translator for reputed clients. The name of his website is konkanicinema.com

He has been a freelance journalist since his teens and is now a regular contributor to Konkani, English and Marathi papers.

A contributor to the Konkani Wikipedia and Konkani Wiktionary, he has also contributed to social activities in Pune since 1965.

.jpg)