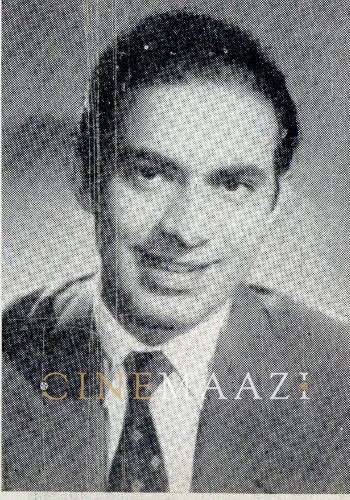

By this writing Shri Nitin Bose is 82 years young. To talk of this patrician of the Indian cinema is to go back to the days of the bioscope, of cinema shows in tents in Calcutta, of the era of Siddeley-Deasy and Durkobf cars of Rabindranath Tagore as well as Fox Kinogram (before 20th Century-Fox itself was formed) of William Randolph Gearst, a sprightly Anglo-Indian less called Comfy Hayde, who dared to be a heroine opposite Kedar Chatterjee, son of Ramananda Chatterjee when Bengali girls fought shy of film acting.

But then, one must begin at the beginning, with his legendary father, H. Bose, who had nine sons, of whom Kartik, Ganesh, Bapi and Babu Bose preferred cricket, and Nitin and Mukul the cinema. H.Bose made everything from the hair oil Kuntaline to Edison’s wax cylinders, and from printing presses to the talking photo graph, as it was then called, H.Bose had a licence for recording as far back as 1905, and recorded songs by Lalchand Boral, father of Raichand. It is Hemen Bose who was the first to introduce the additive process called autochrome, which became extinct because it later become subtractive.

H.Bose made everything from the hair oil Kuntaline to Edison’s wax cylinders, and from printing presses to the talking photo graph, as it was then called, H.Bose had a licence for recording as far back as 1905, and recorded songs by Lalchand Boral, father of Raichand. It is Hemen Bose who was the first to introduce the additive process called autochrome, which became extinct because it later become subtractive.

“I used to do the processing in my school days for father” said Mr. Bose “And he took me along to the tent shows run by

J.F. Madan to see the new bioscope, which consisted of moving pictures and black and white shadows. Knowing I was developing an interest, father used to buy me books published in America and England, and after my teacher had left in the evening and after dinner, I used to read those books to see how those pictures were made. In 1914 just before World War I started, father bought me my first cinema projector and taught me how to work the machines.

In 1914 just before World War I started, father bought me my first cinema projector and taught me how to work the machines.

By 1917 I had my own camera, projector, printing machine and processing arrangements at 52 Amherst Street and 62 Bowbazaar. In 1917, Prasanta Mahalanobis and Rathida (Rathindranath Tagore, the poet’s only son) took me to Bolpur. Rabindranath was a close friend of father’s and at Uttarayan, on the roof, he arranged a dance recital by the girls, which had a definite pattern, and then Tagore asked me to photograph it. I filmed it patch by patch sequentially, and then processed the entire film in an improvised lab in Prasanta Mahalanobis’s laboratory in Presidency College.

Rabindranath was a close friend of father’s and at Uttarayan, on the roof, he arranged a dance recital by the girls, which had a definite pattern, and then Tagore asked me to photograph it.

Then I developed and printed it at home, processed and joined it in the lab, and then projected it before Gurudev. He loved it and immediately said: “Let’s have dinner, and then we’ll see it again”. I was so happy, was like being in Heaven I couldn’t eat. It was if I was on a wave. Show ended at midnight and it was 17 minutes, at 16 frames per second. I gave the film to Tagore and it is now Shantiniketan’s property. Rathida put his hand on my head, and when I did pranam to Rabindranath I started crying. So Gurudev said to Rathida, “Wipe his tears”, and then he turned to the girls and said, “We shall see it again” What great moments - these can’t be bought with money.

I only became a professional in 1920, when the Maharaja of Tripura asked me to photograph the Khedda of wild elephants, I went to Tripura jungles with Karim Bux, my faithful servant and after filming for 2 1/2 months, came back home and processed the film.

“In 1911 the King and Queen of Belgium came to Calcutta and there was a reception at a huge palace belonging to the Cohens, somewhere near Loreto and Camac Street. I filmed the reception and it was bought by William Fox of Hollywood. But I only became a professional in 1920, when the Maharaja of Tripura asked me to photograph the Khedda of wild elephants, I went to Tripura jungles with Karim Bux, my faithful servant and after filming for 2 1/2 months, came back home and processed the film. It was bought of William Randolph Hearst, the newspaper owner and released internationally through international Newsreel Corporation of New York. I was paid one dollar per foot, which in those days was a fabulous sum, since a dollar was worth Rs. 2 As. 10 1/2. In a middle-class hotel in Calcutta You could get a good Bengali meal of rice fish curry (two big pieces of fish) daal, bhaji, ambal and lavish second helpings for one anna or four pice.

“I gave my dollars to mother. She looked at the demand draft, then looked at father’s photo, reflected in the mirror, and said with tears in her eyes: “Etayi tui niye neh, eta diye tor bhaat kapor paabi (You take this, you will earn your rice and clothes through this). So far, I had been off and on an exporter of furs, such as snow leopard, to England and cinema had been only my hobby. But when mother said this I gave up furs and started making films.

In 1924, Jaigopal Pillai, Himansu Rai’s assistant for Light of Asia came to know I had all the equipment and came over to say he had the backing of a Marwari financier to direct Punar Janma and wanted me to be his cameraman and process and develop his film.

In 1924, Jaigopal Pillai,

Himansu Rai’s assistant for

Light of Asia came to know I had all the equipment and came over to say he had the backing of a Marwari financier to direct

Punar Janma and wanted me to be his cameraman and process and develop his film. Mother met Mr. Pillai (although I was then 26 years old) and gave permission. We had only Anglo-Indian ladies for female characters, and

Comfy Hayde played the lead opposite

Kedar Chatterjee, who played the Rajput prince who falls in love with the poor village girl. It had a happy ending. We shot the film in Jaipur, and the entire company moved there. I took the test shots of Comfy for Pillai (in 1924). The film was completed in 1925. It was released at a cinema in Dharmatala and was a roaring success.

Then Naresh Mitra, the very famous man of the Bengali stage backed by Satish Mitra and Nagen Bose, proprietors of Laxmivilas hair oil, financed the first, silent Devdas in 1928, which Barua made as a talkie in 1934-35.

Then

Naresh Mitra, the very famous man of the Bengali stage backed by Satish Mitra and Nagen Bose, proprietors of Laxmivilas hair oil, financed the first, silent

Devdas in 1928, which

Barua made as a talkie in 1934-35. I was the cameraman for both Devdases. This Devdas was also a roaring hit, and since Madans owned all the cinemas it was shown in one of their threatres. Then

Sisir Bhaduri came along and made a picture in 1927 in which he was producer, director and hero. It was based on a story by Tagore, and the heroine was

Kankabati, opposite Bhaduri. In the course of making that film P.N.Roy now dead and some-how distantly related to Himansu rai, came over suggested that I should be the technical director for his films. Having my own equipment was a very important factor. So we made

Chor Kaanta, directed by

Charu Roy, the story and direction were by Premkumar Atorthy.

Sound Films

I was highly enthusiastic, loved the idea and went to Bombay to see what was happening and in Imperial Studios I found Ardeshir B. Irani filming Alarm Ara. The sound was on the Tanar system for India’s first talkie.

“While we were making every evening a gentleman in posh attire, with a tin of posh cigarettes, came to the studio driving an imported French Delage car. He was

B.N. Sircar the son of sir N.N.Sircar. Sircar was behind the international Film Corporation. During the making of

Chor Kaanta and

Chashar Meye we had naturally been thinking of sound pictures. I was highly enthusiastic, loved the idea and went to Bombay to see what was happening and in Imperial Studios I found

Ardeshir B. Irani filming

Alarm Ara. The sound was on the Tanar system for India’s first talkie. I was there for one and a half months learning how, why and when. My brother Mukul, then a research scholar in electronics in my grandfather Sir J.C. Bose’s institute, jumped at the idea when I suggested that New Theatres switch over to sound. One William Demming came all the way from the USA to train Indian recordists on a three-year contract. He met Mukul and after six days of the association, Demming said: “It is useless wasting time. There is nothing I can teach him. “So Mukul took over as the first sound recordists. Mother gave her permission. And that is how it all began.

.jpg)