A Setting Sun: The Forgotten Mehfils of Muslim Socials

29 Apr, 2020 | Short Features by Cinemaazi Team Member Rajlakshmi Bhagawati

Indian cinema, unlike Hollywood, has an ambiguous relationship with the idea of genre. Almost every film in Hindi cinema has romance, drama, comedy and a lot of singing and dancing. Hindi cinema has always latched onto emotions and hence the audience has learned from repeated visual and audio clues to recognize a genre. After all, a genre is what is collectively believed in by both the audience and filmmakers.

The Muslim Social, a sub-genre in Hindi cinema, was a hit template for films that started during the early 1940s.

The Muslim social, a sub-genre in Hindi cinema, was a hit template for films that started during the early 1940s. The sets of the film, costumes, Urdu laden Hindi language used in dialogues and songs helped create the façade of the make believe world of the Muslim social. With rich sherwani clad men sitting around the courtyard adorned with beautifully engraved pillars and arched doorways outlined with sheer curtains, their lips stained with paan, the spittoon placed conveniently nearby and the women dressed in anarkali salwar kameez with the dupatta draped to cover their heads - the Muslim social had it all. This beloved film genre of yesteryear followed the same trope of love stories sprinkled generously with drama, beautiful lyrical songs, comedy scenes and the cherry on top- a happy ending. The only difference was the representation of Muslim culture and characters on the big silver screen, as the name suggested. Apart from setting up the Muslim context, the ‘social’ in the sub-genre was the core principle set out in the beginning. At its inception, the sub-genre intended to have progressive portrayals of the Muslim world. Unfortunately, the progressive aspect went down the hill as the sub-genre approached its demise.

The genre of the film was established right at the opening credits. Take for instance, Chaudhvin Ka Chand (dir. M Sadiq, 1960), which starts with the images of domes, minaret and arched doorway looking into the imambara.

The genre of the film was established right at the opening credits. Take for instance Chaudhvin Ka Chand (dir. M Sadiq, 1960), which starts with images of domes, minarets and arched doorways looking into the imambara. The song, Yeh Lucknow ki sar zameen begins playing in the background, accompanying the images. One can say that the lyrics of the song flow like a nazm. The lyricist was Shakeel Badayuni, who had a long association with the sub-genre. The audience automatically recognizes the Muslim markers.

Mehboob Khan’s Najma (1943), one of the first films in the sub-genre, had an influence of Urdu in its dialogues, yet it had a strong footing in spoken Hindi. The film’s narrative focused on education and rationality took precedence.

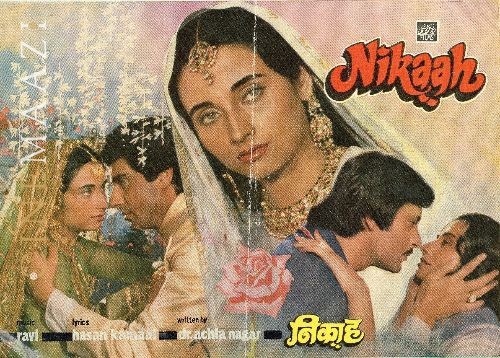

The films in this genre employed a mixture of Hindi and Urdu language. Upon closer inspection of the films, the changing aspects of the Urdu heavy Hindi language the characters conversed in largely marks the ‘Muslim identity’, and the change the Muslim social underwent. Mehboob Khan’s Najma (1943), one of the first films in the sub-genre, had a trace of Urdu in its dialogues, yet it had a strong footing in spoken Hindi. The film’s narrative focused on education and rationality took precedence. It struck the right balance, and as a result, it appeared as if the Muslim social would become more common as both the trade and the audiences embraced the way filmmakers could package entertainment as well as social messaging. Unfortunately, with the passage of time, the sub-genre became reduced to its markers like the language. Four decades later, Nikaah (dir. B. R. Chopra, 1982) provides us with its exaggerated use of Urdu and the shayarana andaaz, which becomes too self-indulgent. In the 1960s, the success of Mere Mehboob (dir. H S Rawail, 1963) took the Muslim social to greater heights, it was the number one film at the year’s box office, but at the same time, it also created trappings that the sub-genre found near impossible to transcend in the years to come. Drawing inspiration from life in Aligarh Muslim University, a location that is seen in the film as well, Mere Mehboob laid great emphasis on education and reiterated the significance of culture and social values. In the film, Anwar (Rajendra Kumar) cannot believe his luck when the girl he falls for in college, Husna (Sadhana Shivdasani) the sister of his benefactor Nawab Buland Akhtar Changezi (Ashok Kumar) is asked to teach her poetry. Nawab Buland Akhtar also agrees to an alliance between Husna and Anwar despite him hailing from an ordinary background but fate doesn’t allow things to work out as smoothly – Anwar is found in the company of a courtesan leading to the breakup of his engagement and the wealthy Munne Raja (Pran) pushes a destitute Nawab Akhtar to marry Husna to him. The film’s social messaging took a backseat with the essential elements of the Muslim social working their charm on the viewer.

In the 1960s, the success of Mere Mehboob (dir. H S Rawail, 1963) took the Muslim social to greater heights

The Muslim social was popular for many reasons, but it surely helped that most of the beloved stars of the audience were associated with it- Ashok Kumar, Rajendra Kumar, Sadhana, Waheeda Rehman, Guru Dutt, Meena Kumari, Rajesh Khanna. The iconic aura of a star signified something central to the film and its genre. An actor’s body of work has a certain consistent value that was asserted through their roles. Like Ashok Kumar who often plays the modern, rational, educated hero- in Najma, his character Yusuf saves his ex-lover’s husband who was about to kill him. In Pakeezah, he plays Shahbuddin, who marries a courtesan and honours the relationship with his estranged daughter. The morally upright character sought to subvert norms and pushed the envelope further for righteousness- a trait of the heroes in the Muslim Social category, at least in the initial period. Character actors like Asrani, Johnny Walker usually provided the comic relief to the narrative and played the hero’s friend. The association of lyricists like Majrooh Sultanpuri, Kaifi Azmi, Javed Akhtar, screenwriters like Saeed Akhtar Mirza and directors such as Kamal Amrohi, Mehboob Khan and B.R. Chopra helped boost the publicity of the films.

Hindi cinema has always been dominated by Hindu characters since its inception. While the norm still prevails, the Muslim social came about as an alternative to address the lack of representation of Muslim culture on screen. It created a space for Muslim culture, brotherhood and morals to be seen on screen. Muslim socials tried to tread the lines of this representation along with modernity in order to portray a vision of the community as a part of the subcontinent. The brief success of the sub-genre was responsible for bringing the minority culture to the screen, even though it mostly focused on the Nawab elites, apart from a few exceptions.

As the genre aged, the later films diverged from the core principle of the sub-genre: the progressive aspect of the films that displayed the Muslim community interacting with socio-political problems

As the genre aged, the later films diverged from the core principle of the sub-genre: the progressive aspect of the films that displayed the Muslim community interacting with socio-political problems and becoming a part of the subcontinent. This was the biggest undoing of the success of Mere Mehboob, which, in a way, made it necessary for the films to indulge in ornamental elements like language to emphasize its place in the genre. If on one hand, the mid-1960s were witnessing popular Hindi cinema becoming more aware of the ‘real’ world with films such as Guide (1965), Phool Aur Pathar (1966), on the other, the Muslim social despite its commercial success limited the narrative by giving precedence to embellishments over everything else.

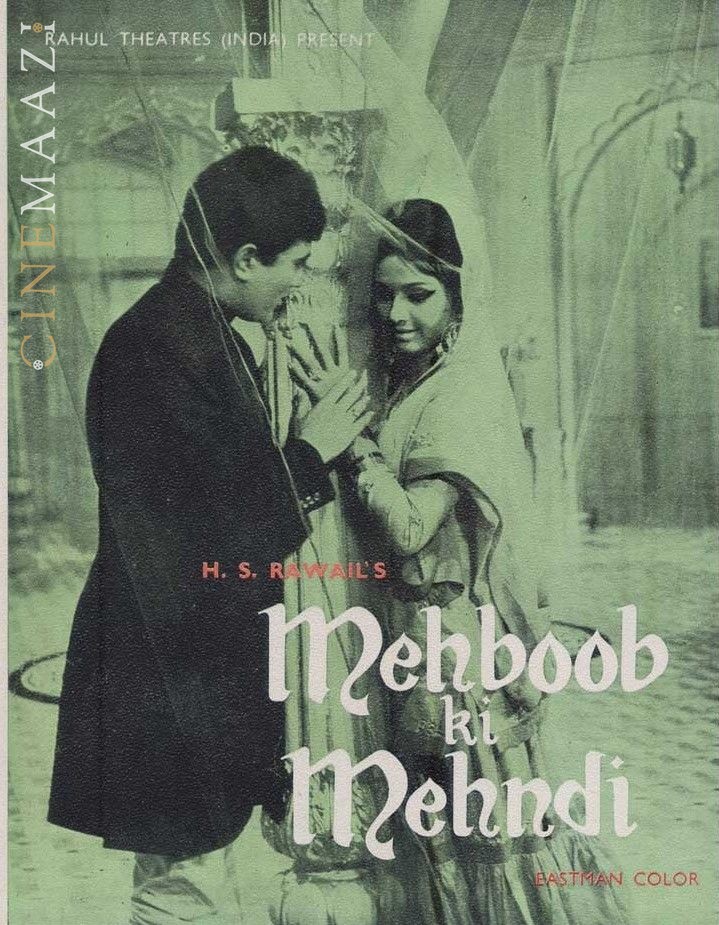

The early 1970s, witnessed Mehboob Ki Mehendi (dir. H S Rawai, 1971), which attempted to revive the sub-genre but failed at the box office too.

The early 1970s saw the release of Mehboob Ki Mehendi (dir. H S Rawai, 1971), which attempted to revive the sub-genre but failed at the box office. It included the markers of the successful template of a Muslim social but stuck to an exaggeration of elements of the sub-genre and retained only a surface level stamp of progressiveness. To summarise the plot in brief: an educated young girl, Shabana (played by Leena Chandravarkar), flees her city after being forced into the role of a courtesan by her evil stepfather. She seeks refuge in the house of a said brother of her daima in Lucknow. In a complicated plotline involving her estranged father, revenge seeking family disputes and a secret in the family as the main contention between the lead pair- the film ends with a happy ending with every issue resolved. Doing injustice to the ideals of the sub-genre, the film fails to deliver on the progressive aspect by placing the onus of shame on the courtesan. To give some context, Shabana’s mother was a courtesan and as mentioned above, she almost became one as well. The shame appears in the form of embarrassment and fear pertaining to her history which makes it uncomfortable for her to come clean to her lover/fiancé Yusuf (played by Rajesh Khanna). The implication of being an immoral woman is attached to the courtesan which is why the film fails to circumvent regression.

While cinema has always reflected society and societal attitudes, it also has the agency of a voice. By attaching shame onto the female characters' body of work, it fails to raise the point of equal standing of the women.

A similar regressive attitude towards the courtesan’s character is also seen in one of the most famous Hindi films of all time - Pakeezah (dir. Kamal Amrohi, 1972). Nargis (played by Meena Kumari), - a courtesan, marries a respectable family scion Shahbuddin (played by Ashok Kumar), but she dies alone in a graveyard after the family rejects her. Her daughter, Shahibjaan (Meena Kumari, in a double role) grows up to be a courtesan and in a tale of love and sacrifice, follows in her mother's footsteps but has a happier ending. In Pakeezah too, Nargis/Sahibjaan carry the stigma attached to the courtesan. While cinema has always reflected society and societal attitudes, it also has the agency of a voice. By attaching shame onto the female characters' body of work, it fails to raise the point of equal standing of the women, especially when one considers the plot’s and character’s worth reinstated by the association with a legitimate father figure. The Muslim socials such as Pakeezah did little for the women in the narrative where the father belonging to a reputable family reestablishes the courtesan’s status in society. Apart from that, the value of the women is always associated with her fiancé/husband/lover.

In the 1980s, Nikaah tried to revive the genre after a dull period but fell into similar shortcomings.

In the 1980s, Nikaah tried to revive the genre after a dull period but fell into similar shortcomings. The monologue by Nilofar (played by Salma Agha) at the end of the film, attempts to push this question of women’s ownership and value attached to the husband, yet it ends with the man deciding on her behalf. Interestingly, the film was supposed to be a comment on the practice of triple talaq (its original title was Talaq Talaq Talaq but Chopra pulled the plug on that decision and changed it to Nikaah at the last moment).The decline of the sub-genre in the late 80s was followed by the rise of the three Khans of Bollywood- Aamir, Salman and Shah Rukh. While the three Khans continue to enjoy their reign over the industry, all three of them have played mostly Hindu characters over the years. Salman Khan featured in one of the last films of the genre called Sanam Bewafa (1991) and popular stars such as Juhi Chawla featured in Bewaffa Se Waffa (1992). Most of Salman Khan’s recent films are released during Eid, targeting a specific audience. A similar strategy was also used by Shah Rukh Khan a few times. While the industry is ruled by perhaps its last big stars - the three Khans - there has been no overt manifestation of Muslim characters in their films for the most part.

The sub-genre that indulged itself in some nostalgia towards its decline period, was reminisced upon recently through the television channel Zindagi. The context was based mostly in foreign countries, yet the representation of Muslim culture triggered this nostalgic association.While the assertion of Muslim identity has resurfaced with films like Raees (dir. Rahul Dholakia, 2017), a comeback for the Muslim social genre is still in question.

Notes

Vyas, Shvetal. “The disappearance of Muslim Socials in Bollywood”. https://www.unisa.edu.au/siteassets/episerver-6-files/documents/eass/mnm/commentaries/vyas-muslim-socials.pdf. Accessed Februrary 1, 2020.

Vasudevan, Ravi S. “ Film Genres, the Muslim Social, and Discourses of Identity c. 1935-1945”. https://www.csds.in/uploads/custom_files/1526553790_Film%20Genre%20and%20the%20Muslim%20Social%20(1).pdf. Accessed February 6, 2020

Das, Asmita. “Is Islamicate a Genre? Looking at Popular Muslim Films through the Lens of Genre”. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/fb6f/d4dcb3b74c1b26b8af58b4524f76be358ea2.pdf. Accessed February 1, 2020

Chintamani, Gautam. “Bollywood’s Monster: The Muslim socials”. https://www.dawn.com/news/722521/bollywoods-monster-the-muslim-socials. February 1, 2020

133 views

.jpg)