Masses, Mainstream And The 'Other'

Subscribe to read full article

This section is for paid subscribers only. Our subscription is only $37/- for one full year.

You get unlimited access to all paid section and features on the website with this subscription.

Not ready for a full subscription?

You can access this article for $2, and have it saved to your account for one year.

Maine Pyaar Kiya (1989) - cried the popular voice! Superlative descriptions marked its success: biggest ever hit; charmer par excellence, et al. Masses were mesmerised by its music. Or may be the fresh faces on the screen did the magic. Followed similar attempts. The din and dazzle of mainstream nudged the other cinema, to be spotted by the Press only when the festival air warmed up!

Over the years, our filmmakers have successfully beat the box office bonanzas by creating an audience which can be identified as 'elite masses'-distinct from the masses who love fights and fisticuffs, romantic songs or swashbuckling heroic deeds. Posing as lovers of serious cinema the elite masses have made their way into theatres to vote for such films as Anjali (Tamil, 1990); Shiva (Telugu, 1989), Ayyar the Great (Malayalam, 1990), and... should we include Maine Pyaar Kiya (Hindi) to this list? All these films are technically excellent works. The dividing line between serious attempts to portray the conditions of contemporary life and gimmickry laden films is being eroded as pseudo concern topped by technical finesse is weaning segments of elite audience. Heard now is the banter: 'we are enjoying an entertaining and skillful one'.

Entertaining skillfully...? An analysis of creme de la creme of 1990 strengthens the feeling that these skillful entertainers are nudging the purists. This is detrimental to the already fragile serious cinema in the country.

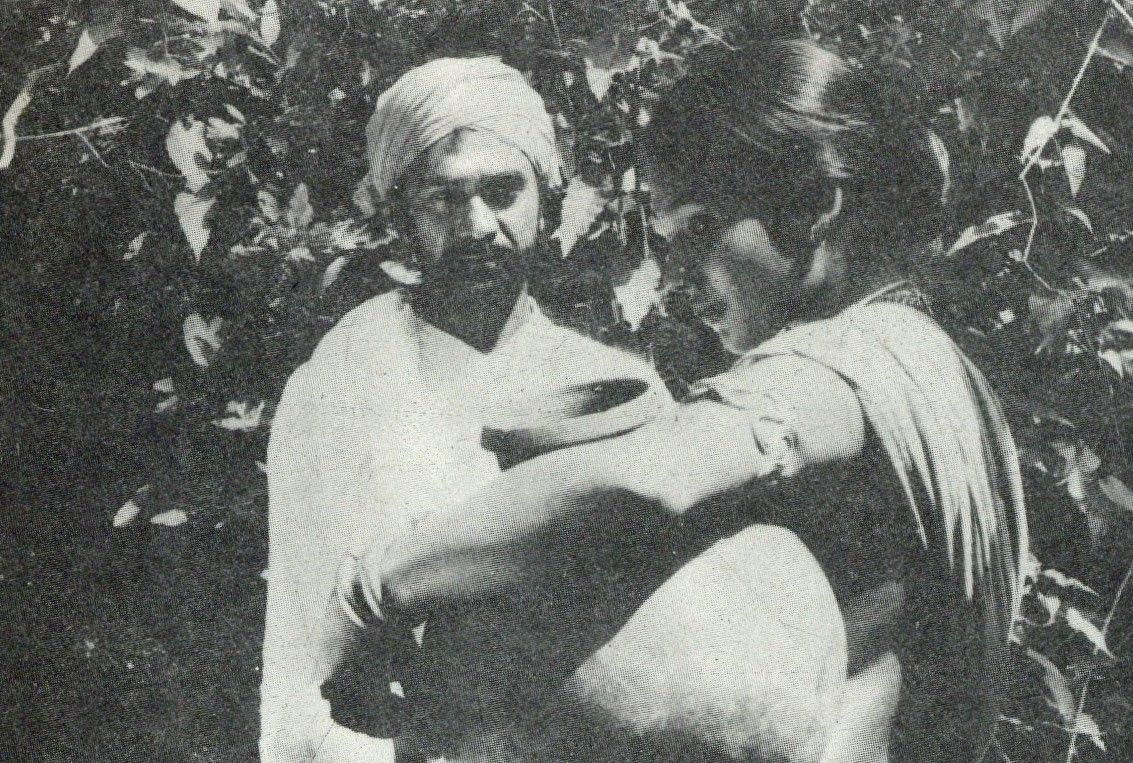

Familiar names like Adoor or Buddhadeb are not seen in the list this year... we have some surprises, though! One such surprise is Vembanad. Vembanad could make our hearts go aflutter with its concern for evolving a new cinematic language. Weaving fantasy and reality the film contemplates on one of the great human weaknesses - sex! Eschewing the common notion of cinema, Vembanad stands out as a promising effort to gather fragmentations of a dream like situation taking shape in a fisherman's island. With no spoken word, save for two bits of discourse on 'sin and redemption' in Malayalam, and two fragmented sentences, Naan Marichu, Naan Marichu (I am dead... I am dead) which the housewife utters as her husband refuses to make love to her, the film has created its own cinematic language:

Malayalam which is the second largest contributor to Panorama this year with four films has once again proved that aesthetics are its concern while reflecting on human conditions. Aparahanam (1991)-portraying the dilemma of a Naxalite, reminds us of Aravindan's Pokkuveyil (1982) though the master's touch is missing. Ottayadipathilukal (1993) examines a domestic situation in presenting inter-relationships which get strained over a mentally retarded child in the house. There is subtlety in this portrayal, though towards the end melodrama takes over. Thazhvaram belongs to 'elite masses' ... doesn't it?

Bengali Cinema takes a back seat this year, with a lone representation from Satyajit Ray, Shaka Proshaka (1990). With his masterly strokes Ray ushers in the confidence that our filmmakers while busy with the art of cinema are equally concerned with the ways of the world - for the comment that comes through this film, identifying insanity as the only segment which is beyond corruption elevates the role of serious fihnmaking.

With almost half of the Panorama 'captured' by Hindi, one has to take stock of goings on Hindi front. When we earlier identified certain films as promoters of 'elite masses', we were only hinting that the success of films like Maine Pyaar Kiya, has made inroads into elite circles now prepared to accept even non-films as serious attempts. Lekin (1990), for instance, is a superbly well-made film, but then, when it thematically strays into the field of fantasy we are forced to recognise this strand which is promoting 'elite masses'. Vembanad on the other hand tries to weave fantasy, aesthetics and contemplation about a human weakness in a very pleasing cinematic language, while technical finesse and the gloss which Lekin sports fail to elevate the fantasy. Ironically at the theatre it is Lekin which is going to stay and Vembanad may not have that kind of reception!

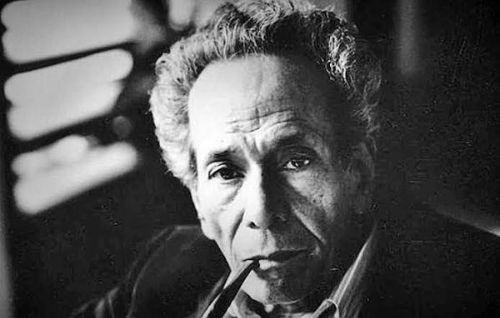

Govind Nihalani's Drishti (1990) and Mani Kaul's Nazar (1989) examine the inter relationships between husband and wife. Govind tries to analyse a situation which borders on adultery. Both Sandhya (Dimple Kapadia) and Nikhil (Shekar Kapur) are portrayed as persons with extra marital relationships. Divorce may not be the answer - but then there is self introspection in the pair: Where did we go wrong?. A highly likeable film save for its verbosity - which is Govind's style these days. In contrast Mani Kaul's stylised presentation has fragmented dialogues, inter-cuts that take us back and forth in time. Mani Kaul's film needs audience empathy with the filmmaker, and once this is developed we are in facile fields to roam with his art. Kumar Shahahni, on the other hand, whose Khayal Ghata (1989) dangled between feature and documentary last year, brings a rare sensibility in Kasha, which is velvetty in its narration.

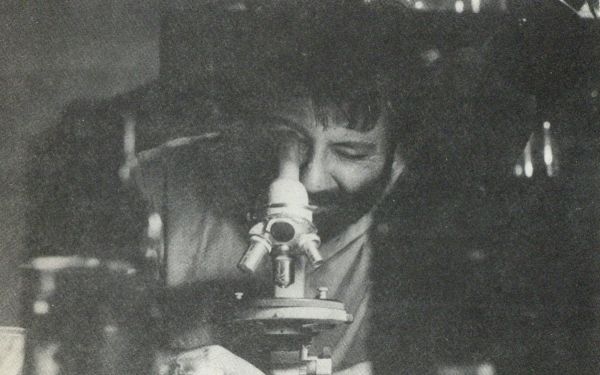

Ek Doctor Ki Maut (1990) exposes professional jealousy in a very charming manner. Based on a real life incident, which drove an India scientist to suicide. Tapan Sinha portrays the battle royale between a dedicated person and the social system. Does Tapan Sinha overstretch Ibsenian qualities? The answer is 'no'. In fact, it is this quality which enlarges the canvas, identifies the causes for brain drain in the country and loss of individuality in our professionals, a fast vanishing tribe. While Shabana Azmi as the doctor's wife makes her charming presence felt in the film, Dimple Kapadia, (Drishti and Lekin) has a competitor only in Mita Vasisth.

That the life in metropolis is no cake walk is brought home again in two films: Sai Paranjpye's Disha (1990) and B. Narsing Rao's Matti Manushulu (1990). Narsing Rao's film, presentation-wise a carbon copy of his earlier Daasi (save for the rural 'gadi' now replaced by the urban construction complex) has a style which enables the cameraman to make his presence felt while the director himself takes a back seat. This explains the lingering shots of construction activity that has come to play a main role in the film - the tracking shots of A.K. Bir (which were also seen in Girish Karnad's non-feature Lamp in the niche) are by now familiar, and it is the signature of Bir's photography. Comparatively Disha does not engage in documentation of a situation, but analyses the causes for rural migration in a thematically strong manner.

By far, I liked Balu Mahendra's Sandhiya Raagam (1989) for its unpretentious approach. Steering clear of pontifications, Balu identifies old age as second childhood and presents the similarities between the two in a heart warming way.

With the elite masses trying to identify the purist middle cinema as the nearest contraption to their fare, attempts at a different kind of cinema continue. Shankar Nag's untimely death has delayed Jo Kumaraswamy, (Anant Nag says it has been shelved for good!) while Sridar Allani is readying his portrayal of a revolutionary, Komaram Bheem (Telugu, 1990). Let us hope some others will also pick up the threads of serious cinema in Telugu.

Anand Patwardhan, Girish Karnad, Gulzar are some of the names which we come across in non-feature section this year. But then is it not the sincerity of Chalam Bennurkar in portraying the lives of children in his Kutty Japanil Kuzhandaigal, or Sashi Anand's Aar Koto Din, which appeal to us? The aesthetics in Arun Khopkar's Figures of thought has captivating qualities.

The other cinema subtly coalesces with human life, while the mainstream loudly divorces itself from realities. The warmth of a simple, (albeit) technically poor, Manipuri presentation Isamou is lacking in the mainstream. This difference is widening over the years, with mainstream busy with its own priorities while the 'other' looks up to only Doordarshan which has become the sole selling window for serious efforts. Incidentally a major chunk of the Panorama films are produced either by National Film Development Corporation or Doordarshan!

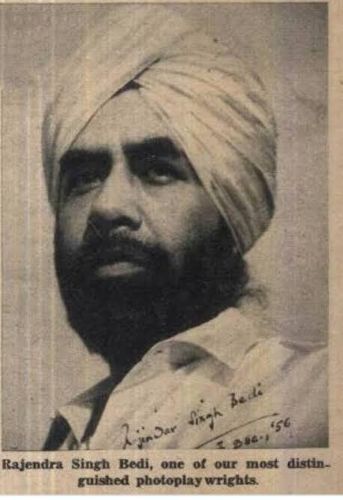

This article was originally published in Indian cinema 1990. The images used in the feature are taken from the original article and Cinemaazi archive

Tags

About the Author

.jpg)