James Ivory, Shakespeare, and the Aesthetic of Slowness

Gayathri Prabhu revisits James Ivory’s Shakespeare Wallah (1965) and identifies in it a sensibility of controlled pacing that later became emblematic of Ivory’s oeuvre…

The first time that James Ivory directed a full-length feature film was also the first time he worked with the producer Ismail Merchant and the author-screenwriter Ruth Prawer Jhabvala. The 1963 film was an adaptation of Jhabvala’s novel The Householder. For over four decades this partnership would go on to create several acclaimed and award-winning movies (such as A Room With a View, Howards End, The Remains of the Day) and leave a distinctive mark on the cinematic culture of the second half of the twentieth century.

Unhurried. That is the word that comes to mind when one thinks of Ivory’s sensibility, and not just because of his preference for mise-en-scenes or lingering close-ups but from something cumulative that perhaps we can think of as an aesthetic of slowness; an invitation to explore narrative layers without the crowding or intrusion of cinematic techniques. It is a cinema that seeks to deepen the storytelling space by pacing it to images and sound that are attentive and respectful to that space. This sensibility was honed to perfection by Merchant Ivory Productions over four decades of filmmaking, and one is curious to know more about Ivory’s first forays in this direction.

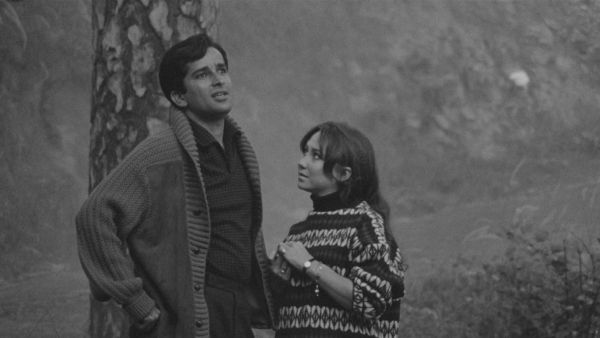

Two years after the debut of this creative partnership (Merchant-Ivory-Jhabvala) came their next offering, this time not an adaptation but an original screenplay – Shakespeare Wallah, starring Shashi Kapoor and Felicity Kendal as the lead pair. The central context of the story is a touring theatre company of British and Indian actors headed by a British couple, the Birminghams, who go around the country performing Shakespeare plays in the early 1960s. The experiences of this group that performs under varied conditions and locations (outdoors, schools, private patrons, small-town stages) had parallels in real life. Geoffrey Kendal and his wife Laura Liddell, who were known for their own repertory theatre company called Shakespeareana, are cast as Mr and Mrs Birmingham. Playing their daughter in the film was their biological daughter (Felicity Kendal), and her paramour in the film was their son-in-law (Shashi Kapoor was married to their other daughter, Jennifer). The lines between autobiography and fiction appear deliberately overlaid in the film.

The self-conscious metanarrative of this film (about professional theatre losing ground to popular cinema) is lyrically and wittily captured in the opening shot that precedes the title. The wide frame fades in from black to the sound of the twitter of birds and we find ourselves in a park with widely spaced gigantic trees awash with slant sunlight. A cycle-rickshaw approaches the camera and circles the tree in front of it while the cyclist rings his bell a couple of times. The cyclist and his passenger are dressed from head to toe in formal Elizabethan garb (complete with powdered wigs); she sits grandly resting her arms on a parasol, looking straight (defiant almost) into the camera as the rickshaw goes by us. After two circles around the tree, the cyclist and his passenger cycle away from us, back towards the patch of sunlight from which they had emerged. But for a slight pan to accommodate the cycle’s approach to it, the camera is a study in stillness, and captures the quietness and humorous juxtaposition so innate to Ivory’s filmmaking.

It is also an invitation for us to pay closer attention to the visual aesthetics of Shakespeare Wallah. The cinematography of Subrata Mitra (renowned for his work on Satyajit Ray’s Apu Trilogy) is unhesitant about pushing frames of low-light conditions often contrasted with dramatic spotlights. It seeks to showcase the theatrical energy and high passions of Shakespearean writing even as it settles into the register of realism that comes from closely following the daily travails of the same group of people.

The screenplay has the challenge of balancing out a plot where most of the characters are in some kind of distress, whether professional, financial or emotional. But even as these worries and anxieties start to build in the storyline, the tempo of the storytelling itself (in the manner in which scenes are constructed and individual shots timed) remains remarkably even paced and eerily quiet. Sanju (Shashi Kapoor) is a young man of means juggling his romantic associations with two performers – Lizzie, who plays roles written by Shakespeare (she is born to English parents but has never seen England), and Manjula, a glamorous star of Hindi cinema who is shown doing the customary dancing-around-trees. The viewer is kept aware of the fact that the days of the theatre are probably numbered and that young Lizzie is more emotionally committed to her beau than he is. But of course no matter how intense or dire or worrisome the storyline may become, the film determinedly stays at its measured tempo.

.jpg)

In the scene, Lizzie explains to her lover that to be an actress is to be seen: ‘People who have never been on the stage don’t know what it is like. It is a wonderful life […] acting is my whole life, without it, I would be nothing.’ This is one continuous flow of action – she rises tearfully from the floor and nestles in the young man’s arms – as the camera tilts up gently and then slowly zooms to her face against his shoulder. It is a crucial moment, an emotional gambit: Will Lizzie give up acting to pander to Sanju’s touchiness about ‘Izzat’ (he explains his idea of honour to her) or will Sanju give up his easy-going situation (in and out of two women’s hearts) to commit to Lizzie? This emotional gambit is also simultaneously a cinematic one: How will the image and sound continue to balance the measured movement of that scene (and indeed the whole film) with the immediacy and heightened pitch of this critical, narrative moment?

The film now transitions to the final scene of the film as Lizzie waves goodbye to her parents and sets sail to England for the first time in her life. The touring company may or may not continue to make a livelihood from staging Shakespeare, but the audience knows that the next generation is likely to make different choices. And the gentle glide of the big ship at the end seems to perfectly embody the delicate and smooth precision with which Ivory has captured multiple stories that get subsumed when generations and art forms make way for whatever comes next. But that carefully composed empathy of slowness is precisely what makes the change bearable, even achingly, briefly, beautiful.

Tags

About the Author

Gayathri Prabhu is the author of four novels, a memoir and a novella in prose poetry. She is also the co-author (with Nikhil Govind) of Shadow Craft: Visual Aesthetics of Black and White Hindi Cinema (Bloomsbury, 2021). She teaches literary studies at the Manipal Centre for Humanities, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Karnataka.

.jpg)