"I am Benegal. I make films too"

A few years ago at International Film Festival of India in Panaji, I found myself a little out of my depth in a room full of heavyweights of Indian cinema. Around an oval-shaped table sat the likes of Krishna Shah, Ketan Mehta, Govind Nihalani, Saeed Mirza and Shyam Benegal. A little removed quietly sat the peerless Adoor Gopalakrishnan. Then there were half a dozen foreign filmmakers from countries like Argentina, Chile and Romania. Filmmakers introduced themselves with total modesty. First Shah, then Mirza and then Nihalani. Every director merely stated that he loved cinema, was into it for many decades and had made a handful of films, some were appreciated, others not so. Gopalakrishnan and Benegal did not grant themselves even that much due. "I am Benegal. I make films too," the veteran filmmaker said, almost self-deprecating in his tone, before pointing to Gopalakrishnan and adding, "He is a legend. He speaks through silence." Gopalakrishnan, in the fitness of things, stayed silent, merely waving at the accomplished gathering. I could as well have been watching a Bimal Roy classic!

Then came my turn, somebody who had never dared to hold even a camera. "I am not a filmmaker nor do I aspire to be one. I just watch films, some of them I review," I said. Amidst ooh and aahs, Benegal Sahab came up with a one-liner that has stayed with me, "So you judge us!" Witty and trenchant, pithy and focussed; just like his work.

A few years later, the impression was re-imposed in two courtesy meetings separated by a couple of years. The first came during a long-drawn-out interview with him for Doordarshan. The way he recalled every tiny detail of his famous 53-episode Bharat Ek Khoj television series made me wonder if his mind had some glue! Or, did he have a backup memory all his own?!

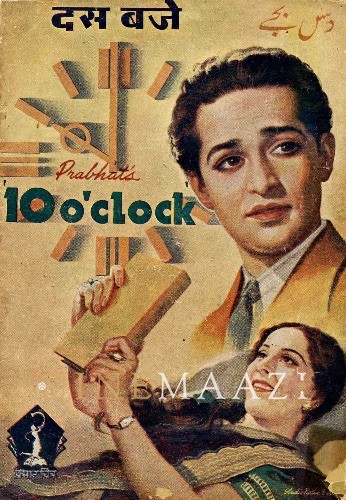

.jpg/img20201214_13334072%20(2)__318x480.jpg)

His integrity, profundity and an ability to bring everybody around amidst all the conversations we had shone through splendidly. These are the characteristics, which have stood him in good stead in Hindi cinema for more than 40 years, ever since he started his cinematic journey with the rather aptly named film Ankur (The Seedling, 1974); a film that introduced Shabana Azmi and Anant Nag. In fact, to millions born in metropolises with attendant privileges, Benegal has been a bridge between India and Bharat. Back in the 70s when everybody seemed caught up with the phenomenon of the Angry Young Man with a beautiful girl as an eye candy, Benegal showed a mirror to Bharat that many of us had started to believe did not exist. With films like Ankur, Manthan (1976), Nishant (1975) and Bhumika (1977), he was recognised as a filmmaker with a searing intensity, a dark brooding quality came to identified with his work — it is an image which has lingered on in the common man's mind despite Benegal breaking the stereotype with films Zubeidaa (2001), Sardari Begum (1996) and Welcome to Sajjanpur (2008).

While he is easily identified as the man who gave voice to the voiceless, his ability to paint a scene with the minutest detailing, his lasting bond with symbolism, his ability to let the silence speak, and his ear for music have not been as well appreciated. Take for instance, his 70s' quartet – Ankur, Manthan, Nishant and Bhumika. Ankur, which is an indictment of the prevalent socio-economic order, grows on you quietly, seamlessly, taking you into a world where chillies are pounded, goats are tethered, the poor live in huts and the word of the landlord is law. No larger than life canvas, no hyperbole, just a rare ability to make the image present not just credible, but identifiable. In its opening sequence, we have a nat (acrobat) performing in front of a long procession which includes the heroine seeking to propitiate the deity for fertility. All around, we have green grass, cows happily nibbling away and birds chirping in the background. Under his lead character's feet though is an uneven field full of thorns, stone and mortar! The symbolism continues with the introduction of the hero: One moment he is a happy young man, who has cleared his school exams, but next moment, as his father puts a brake on his ambition to study further, he stands behind a window, its grills appearing more like the bars of a jail. Benegal explores fine details here: The young man's plan is conveyed to the father by the mother — those were the days when in a large part of our society sons did not speak directly with their father and mother acted as an intermediary.

The same immaculate eye for detail comes to the fore when one watches Manthan, a film that encapsulated the vision of Dr V Kurien, the man who made the White Revolution a reality. Here Benegal, having earlier made a documentary on Operation Flood, is able to use his research to fine effect and weave in a comment on caste politics without launching into a sermon. Everything bold, everything pertinent, everything subtle. Again, the film speaks eloquently through its pauses and silences, its slick camera work and a fine interplay of light and shade, reminding one of Bimal Roy. Such is Benegal's eye that he makes sure every villager in the film seems genuine with just the right folds in dhotis and pagdis.

In Nishant, he talks more disparagingly of a social order, which is not designed to deliver justice – policemen are wimps, a school teacher lives with impotent rage and common villagers, dark skinned and poor, look on helplessly. M live at the pleasure of the feudal lord; and in such an atmosphere, women are meant for the pleasure of men; there is a line in the film that compares women to cows. It is delivered with such disarming simplicity that it becomes a masterpiece. Nishant too is rich with symbols: We have a thatched roof and a cowshed; unpaved roads and courtyards, a brass tumbler for washing the face, miswak for cleaning the teeth, lanterns hanging by the ceiling, a watch on the wall... all express rural life beautifully. Not to overlook a stick in the hands of the feudal lord, a horse carriage on hire for the teacher and fancy jeeps and mobiles for the zamindar's ilk!

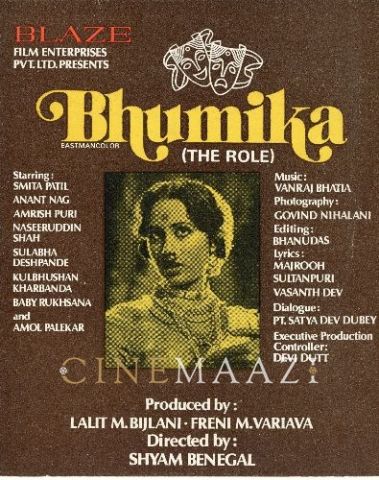

Similarly, in Bhumika, based on the autobiography of the doyenne of Marathi theatre and cinema, Hansa Wadkar, he allows words to be improved upon by silence. A rare film, talking of the world from a woman's perspective, in which the protagonist, Smita Patil, in a career-defining role as Usha, attempts to figure out her identity – 'who' she is and 'what' she is. The film grows through a series of relationships, each one peeling off a layer of patriarchal system. The best line though comes at the end, when she is told, "Beds change, men don't". Incidentally, such is his famed meticulous approach that when writer-academic-filmmaker Sangeeta Dutta decided to do his biography, she watched 23 of his films and went to the sets of Zubeidaa, which was then being shot in Jaipur! That was the only way one could come even remotely close to doing justice to the life story of a man who always counts Guru Dutt and Satyajit Ray among his early inspirations and in his own way has treated cinema as his own alternate world, where he can recreate his dreams, in fact, live them for a few hours.

.jpg/img20201214_13342765%20(2)__600x443.jpg)

If in all these films, as indeed in later ventures like Mammo (1994) and Suraj Ka Satvan Ghoda (1992), Benegal displays his rare ability to converse forcefully through silence, but for the discerning, he also exhibits an ear for music. Take for instance the Preeti Sagar number in Manthan, Mero Gaam Katha Parey, a Gujarati folk song. This National Award-winning song was sung by a singer, who, until then, was identified by the masses for the popular song My heart is beating. Only Benegal had the ability to discern a folk singer in Preeti Sagar! This ability is also evident in Junoon (1978), where Vanraj Bhatia's background score is remembered to this day, and in Sardari Begum, where many doubting Thomases were silenced, as the music was the soul of the movie and Benegal captured this essence beautifully. Not to forget Mammo, where he used Beethoven's Fifth Symphony in a seamless manner with the lead character moving around in a black burqa. Nobody could have imagined that a movie on such a subject can actually use Beethoven to carry the narrative forward.

Incidentally, another trait of his has gone largely unnoticed — his ability to portray his Muslim characters as normal people, not somebody who would go around with a rosary in his hand or a young man who would break into a gaunt/di. He treated the Muslims as human beings who breathed, lived, loved and died like other fellow human beings. Between birth and death were woven many an emotional tale, as so memorably depicted by Farida Jalal in Mammo, a film that touched many a heart with its depiction of displaced Partition victims longing for their motherland all over again.

More recently, when Hindi cinema often preferred to show Muslims as merely gun-toting militants, he made a bold attempt to come up with a film like Well Done Abba (2009). Talking to me about the film then, he happily explained his point of view. "Yes, it is a rare film with a Muslim as a central character, but honestly I did not think of him as a Muslim, just as a character. The problem with our society, and indeed our films to some extent, is that we tend to give a certain identity to people. So a Muslim has to wear a skullcap, wear a sherwani and talk in a certain manner whereas, in reality, they are like anyone else. I won't recognise a Muslim on the street unless he wears a cap or grows a beard. I ask, why cannot we have everything perfectly normal? Why cannot we talk of Muslims whose problems are like those of their countrymen? I am sure in everyday life a Muslim responds to everything first as human being. He too feels pain, he too laughs, he too feels the pangs of hunger. It is only if you provoke him on certain aspects of culture, does he respond as a Muslim."

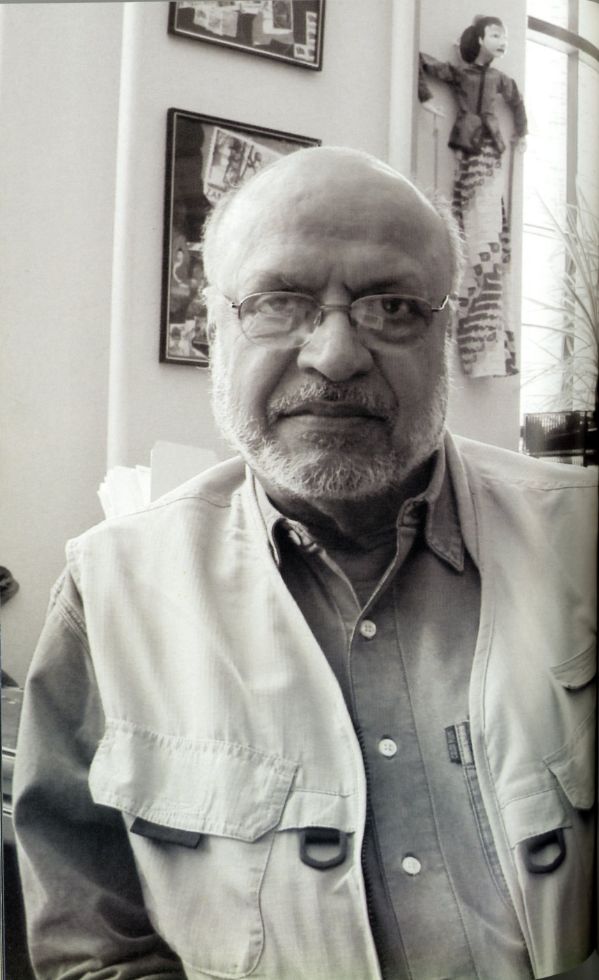

.jpg/img20201214_13350209%20(2)__337x480.jpg)

Around four decades of filmmaking later, it is this desire to speak the truth, the ability to communicate with a few words spoken (many silent but unexpressed), that stays with me. And, indeed, with millions who have followed his journey right from the time he was a copywriter with Lintas to a documentary filmmaker to a feature filmmaker of international renown, a man for whom even our commercial cinema rewrote many a rule. The proof came in 2000 when one of his less-celebrated works, Hari Bhari was released. The film had no masala, no chutzpah, no candyfloss to attract the first day-first show bubblegum brigade at multiplexes. Yet, the halls made an exception, giving the film niche treatment and releasing it in prime shows. Defying all odds, Hari-Bhari had more than 60 per cent footfall in the first show! Interestingly, the otherwise sedate film had its moments of stray humour, something which is common to all Benegal films. Understated situational humour, a world removed from slapstick or banana peel variety Hindi cinema often loves to embrace. It is this ability to see a smile amidst all doom that has stayed with him, whether he has chosen his subjects from history as in Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose: The Forgotten Hero (2004) or literature as in Suraj Ka Satvan Ghoda, which was based on Dhararnvir Bharati's novel or The Making of the Mahatma, based on Fatima Meer's work, The Apprenticeship of a Mahatma or purely commercial ventures like Zubeidaa. It is also an approach to cinema that has been richly rewarded. From the Padma Shri in 1976 to Padma Bhushan in 1991 to Dadasaheb Phalke Award in 2005, besides numerous National Awards for best films, Benegal has been the voice to listen to, a man to look up to, for generations of filmmakers; not to forget thousands of students of FTII where he moulded many a young mind as a Chairman from 1980-83 and again from 1989-92.

It is reward well earned by the who never liked the term ‘art-house’ cinema or parallel cinema’ for the cinematic movement of the 1970s, which he in many ways, pioneered with the likes of Mrinal Sen and later Govind Nihalani and Goutam Ghose. Films, he always believed, are about teamwork. They may carry a director’s vision but they are not a solitary pursuit. As he once described them, ‘Films are a social art’. It is an art that the he has perfected so beautifully.

Such is the class the man. On his not-so-good days, he has been very good. On his good days, actually excellent; and many a moment, simply a genius.

This article was originally published in the book Legends of Indian Silver Screen: Dadasaheb Phalke Award Winners (1992-2014). The images are taken from the original article and Cinemaazi archive

Tags

About the Author

.jpg)