Good Old Silent Days and After

Subscribe to read full article

This section is for paid subscribers only. Our subscription is only $37/- for one full year.

You get unlimited access to all paid section and features on the website with this subscription.

Not ready for a full subscription?

You can access this article for $2, and have it saved to your account for one year.

I began my career, which covers over half a century, as a cameraman, in the good old silent days. I have worked with such eminent personalities as the late Dhiren Ganguly, Debaki Kumar Bose, P.C. Barua; and three personalities of more differing temperaments it would be difficult to find - Dhiren Ganguly the businessman, Debaki Bose, the philosopher, and Barua, the artist. These fifty odd years have also given me an opportunity to play at being a producer as well as a director in several films, but the mediocre quality of my work convinced me that my true forte was of a mechanic, which, in my egotistic way, I now call “Engineer”. If I did anything worthwhile as a cameraman, (and I believe I did, if most friends are to be believed,) it was certainly not due to any artistic ability, but purely due to the mechanic in me. This admission is rather discouraging when I sit down to scribble something which is going to be read by members of the artistic elite in the motion picture racket. But then, I have already committed myself. I only ask your indulgence for the excessive use to the first person singular.

It was round about the time that I was working with Himansu Rai at Bombay Talkies. It was early 1935, or was it a little earlier? Two cameramen had come to India from Hollywood to obtain material for a documentary about central India, and that that too in colour. They needed the services of an assistant, and I lent them mine, a young man of 20 or so, Dronacharya, by name, who later was to become one of our leading cinematographers. Six months later he came back talking all the time of colour as if black & white was already dead. The enthusiasm was infectious, and I caught it.

First Time Colour

With the help of finance that a very good friend advanced to me, I succeeded in building India’s first colour processing and printing machines. Today these machines would look like Mecano toys, but the fact remained that they worked, and I succeeded in getting a patent for my process.

Although only a two-colour process, the commercial results were acceptable. Things might have improved, had not the Second World War intervened and cut off my supplies of raw stock. I had perforce to close down, but it gave me the confidence that I could construct continuous processing machines.

By this time, I was working at Ranjit with Sardar Chandulal Shah, and in his zeal to modernize, he through getting a few such machines from Kodak or Agfa. I implored him to let me have a try making them myself. I am still wondering whether the Sardar had real faith in me, or it was a bania’s natural desire to save money. I was his full-time servant and he would not have to pay anything extra. He decided I could go ahead. During the time that the machines were under construction, my colleagues often wondered aloud - why was I bent on wasting the boss’s money? But, when, after a year and a half, two fully automatic machines, in all their gleaming chrome, started turning their wheels and spitting out film at the then fantastic speed (?) of 30 feet a minute, the entire studio turned out to gaze and wonder. I was so elated I decided to go into business on my own.

First Colour Lab

And then came colour, this time in earnest. My friend A.J. Patel was an agent of the Gevaert Film Co., and Gevacolour had just been introduced. He got a roll or two and had it exposed, and sent back to Antwerp for processing. The results came four months later, and were enthusiastically welcomed. However the industry could not brook this four months’ delay. A.J.( as we affectionately called A.J. Patel ) decided to build a laboratory right here in Bombay, and entrusted the work to me.

With Madras “going colour,” things began to hum in Bombay once more. I remember a policy meeting of a committee appointed by the Government of India, at which one of the members, Mr. J.B. Roongta, vehemently opposed the introduction of colour saying that it was much too expensive for the country. And yet this very Roongta was the first to go in for colour in Bombay after A.J. Patel’s now famous Film Center.

One could scarcely expect a ‘stunt’ film producer like Homi Wadia of Basant Studio to go in for colour, but even he thought that there was no other choice.

I am nearing seventy-eight now and my only wish and prayer is that I shall go on working as I do now and when my time comes, I shall be at my working table.

This article is a reproduction of the original published in Fifty Years of Indian Talkies (1931-1981) published by Indian Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences, Bombay.

Tags

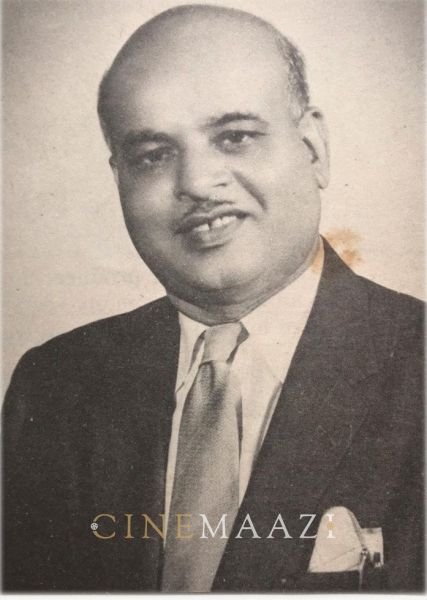

About the Author

.jpg)