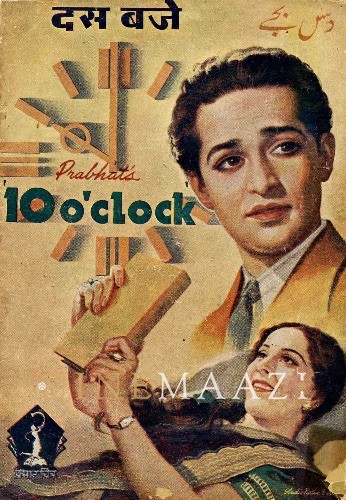

Evolution of Film Music in Indian Cinema

For a little over 50 years, lovers and fans of Indian classical music have read obituaries written about their great love, Indian classical music! The cause of its death, it has been pointed out frequently, is "Film Music, which has spread like a cancer." Few realise that film songs also come from a classical tradition. The expression and art of the people have an eclectic quality about them. It is this quality that gives folk art the strength to touch the hearts of many. As films started using sound, audiences grew in number and film music had to develop on such an eclectic base. A common denominator became necessary. They called it "mass appeal". The branching out from classical tradition came when a small orchestra began to be used, to accompany singers. At its inception half a century ago, it was quite Indian in composition. It still has several Indian instruments. In its sound and mode of expression too, it is unmistakably Indian. However, the size of this ensemble has grown continuously from 1940 onwards.

"Old songs had real melody; today the songs are vulgar and banal and try to make up by loudness what they lack in musicality." People in their middle age often react with this kind of sensitivity to contemporary film songs. They do not realise that each generation has its own pop-culture. And as they pass their youth, they try to elevate it to semi-classicism through nostalgia.

The business world of the music industry, looking for big profits on small investments, has been able to cash in on the trendy nature of this sub-culture. To some extent, the industry itself sets new trends. By an organised machinery which manufactures "hit music" and rams it down the throats of audiences, this industry achieves its aims of monopolising the profits. This suited everyone concerned until large-scale piracy and the proliferation of cassettes began to eat away all profits. Recording companies have become wary of technological advances and the quantity, if not the quality, of film songs is on the wane. The music directors, composers and singers find them-selves at a crossroads. How did this happen?

.jpg/img20201215_15393233%20(2)__414x480.jpg)

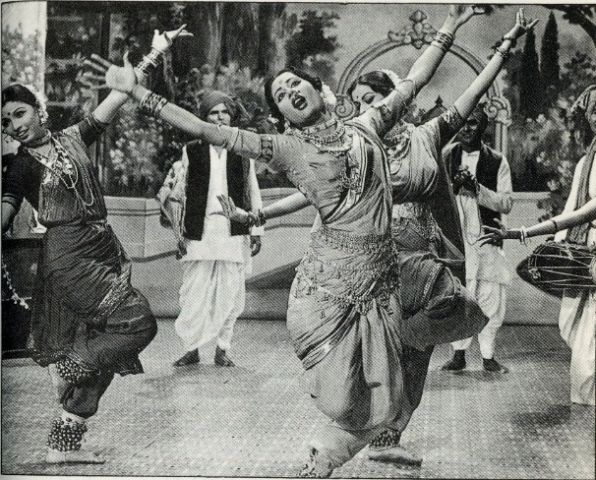

In the late 40s and 50s, film could, for the first time, hope to reach the rural masses. The music from films most certainly did. Songs started borrowing heavily from folk culture. They had to compete for a place in the rural psyche which had a penchant for folk songs. Bengal, Punjab, Rajasthan, U.P., Himachal Pradesh—all contributed to a growing repertoire of film music.

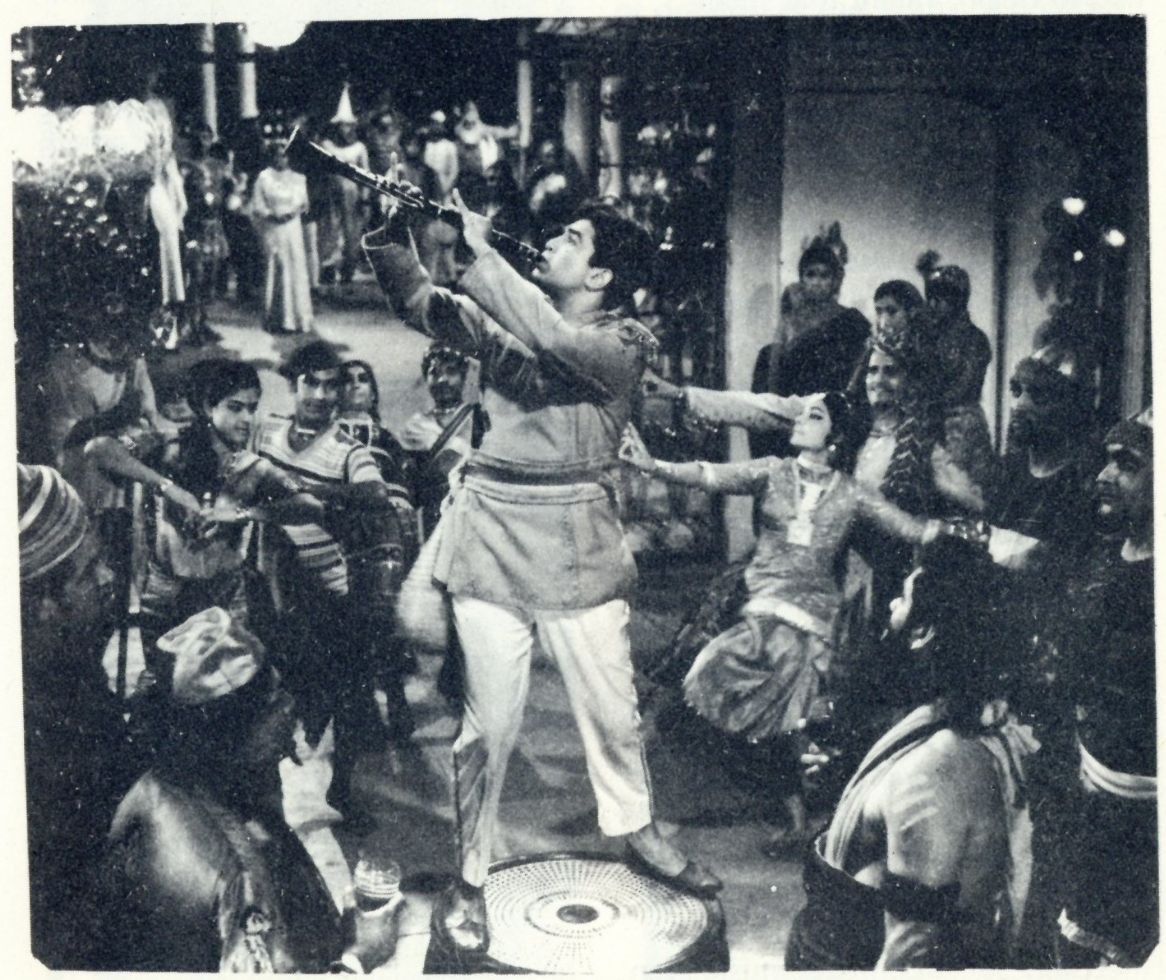

Prosperity in urban areas was perhaps the cause of the popularity of westernized Indian songs in the late 50s and 60s. Growing industrial collaboration with the West and greater communication facilities, brought in a steadly supply of Latin American music and Jazz into urban Indian. Bombay music directors knew that they were now vying with such music for the attention of urbanised youth—a typical city youth who wore mod clothes, ate at restaurants, saw Hollywood movies and listened to hit-songs in Jukeboxes by paying 25 paise. Bombay and subsequently Madras and Calcutta, went mod, started using Sambha rhythms, tenor saxophone, piano accordion, Bongo drums and the like.

The seventies saw thousands of Indians going to West Asian countries following the petro-dollar boom. Once again, there was a new marketing area—oil-rich countries and Indians getting richer working there, were willing to buy film songs which sounded like Arabic music. They used Arabic instruments like Quanun, Oud, Rebab ; disco-rhythms, qawwali formats, Arabic maquams, Urdu lyrics to go with visuals of Dervish or belly dancers. The beginning of the seventies saw an enormous increase in the popularity of film songs. Music directors became the 'stars'. The transistor revolution of the fifties, which made radio sets cheaper, was followed by a boom in long-playing discs and record-players.

Simultaneously and consequently, the commercialisation of All India Radio's "Vividh Bharati" and of Doordarshan (TV) pushed the sales of film songs to unprecedented heights. This resulted in a phenomenal increase in the budget for music in films.

When the Indian 'New Wave' was about to start, filmmakers with small budgets were understandably put off by the high prices quoted by established star music directors. Economic constraints and lack of experience made the communication gap between prospective filmmakers and hardboiled music-men even wider. A search for talent had to begin. Talent that small-budget films could afford.

The Bombay film industry is notorious for its appallingly short-lived memory of success. It has not been exactly kind or encouraging to music directors who leaned on our traditional music. For the New Wave directors-producers, it was not very difficult to locate such talented yet neglected composers. Several of the once-successful-now-forgotten tribe of composers made their return to the screen through these new low budget films. It did not take long for them to realise that their return was not so much for their forgotten talent, as it was for their more readily available services at affordable prices. Some producers found it fit to employ absolutely new concert musicians, but all of them discarded the new and the old low-budget music directors in preference to commercially successful star music men as soon as they could afford them. This resulted in a curious combination of poor old wave music in poorer new wave films!

.jpg/img20201215_15402786%20(2)__477x480.jpg)

An unforeseen factor that rocked the film music industry violently was the proliferation of cassettes. Some years ago, a monopoly concern produced 87% of its discs for film songs. The cost of manufacturing a disc for distribution was prohibitive for any musician who could not go through the film industry. Such artistes have now found a new avenue for their creations in cassettes.

The demand for cassette& has been increasing continuously. A Ghazal singer a Sarod player or even a mimic or a humorist with his spoken word, can today hope to make himself available to a mass audience through these gadgets. The diversification of entertainment channels drains the customers' pocket and a sizeable share of his expenses goes on film music.

From the point of view of the investment-profit ratio, such non-film cassettes are a much safer proposition. You don't need a large orchestra, neither do you need special effects in music that the visual aspect of the film might demand. Lyrics are not written afresh. Classics like those of Jigar, Ghalib and Dag can be used without paying a royalty. Of course, these advantages have not gone unnoticed by film people. Producers often assume a stance on this issue. They claim to adhere to India's rich culture and great heritage in their films. But this hardly solves the problem.

All along, film music has been governed by the economics of the industry. Producers claim to be the barometers of public taste. Film song production is in the hands of special interest groups whose main purpose is to manufacture music for the masses to provide them with some relief from crushing social and economic pressures.

Film music is made in dream factories. The urban low and lower-middle class are growing in number and the masses moving to cities get cut off from their cultural roots in rural India. They are badly in need of dreams. In the slums of Bombay, Calcutta, Bangalore, Madras, a rootless, uncultured hungry man would like to sing and to listen to music that is a mixture of his hopes and dreams and facts and fiction. There are cultural leftovers; he must use them; he cannot worry too much about the nutrient qualities; he is hungry.

This article was originally published in the journal Indian Cinema's 1982-83 issue. The images used in the feature are taken from the original article.

Tags

About the Author

.jpg)