The Post-60s Family Drama: Changing Times, Changing Tropes

A Sunday afternoon, as a child, was only complete with the matinee show we watched together as a family on the TV. Most often the films that played at the hour were the sappy family dramas, meant to be a complete entertainment package. Romance between the hero and heroine, some tension in the family, a whole lot of drama with lots of tears, laughter and occasionally a few action scenes added for the thriller enthusiasts made these films extremely popular with its audience. If one takes away the glitter from the films, it’s always a simple tale of the obstacles the families on screen went through.

Family is a place of belonging, a feeling of safety, a feeling of comfort everyone desires to return to at the end of the day. This means, we seldom think of it as an institution. Family governs an individual’s moral conduct in society as per the existing hierarchies that are legitimised through practiced traditions. The onset of “modern” (read: western) changes that supposedly threaten the family structure have always loomed over the Indian society, even before liberalisation occurred. Like any social phenomena that has a ripple effect in unthinkable ways, when India went through liberalisation in 1991 it refashioned the social fabric of daily life. Apart from a free market influx of MNCs, the Indian family system also went through the inevitable change fate awaited it. But these rifts and tensions did not appear with liberalisation, they had been present for decades prior. Popular Hindi cinema has in a range of ways depicted the tension our society underwent across decades. In this essay, I will look at a few notable family dramas from the 70s till the present times, attempt to map the changes they undergo.

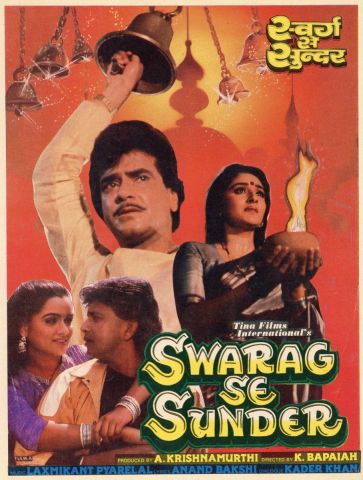

The most common representation of the family in the genre has been a Hindu Joint Family, was duly noted by scholars and critics. A common thread that continues from here till the late 1980s was the anxiety of a disintegration of this structure. In Swarag Se Sunder (K. Bapayya, 1986), Vijay Kumar Chowdhury (Jeetendra) and his wife Laxmi (Jaya Prada) are childless, due to which Laxmi is taunted by other women in gatherings. His step-brother Ravi (Mithun Chakraborty) falls in love and marries the village businessman Milawat Ram’s (Kader Khan) daughter Lalitha (Padmini Kolhapure) through his bhabi’s help, who convinces his brother. The happy ending is delivered through the reunion of the two couples after they overcome the misunderstandings and obstacles laid in their way by malicious relatives.

Similar tropes are used in Ghar Ho Toh Aisa (Kalpataru, 1990), however, here everyone is abusive towards Sharda (Deepti Naval), the daughter in law, except her devar Amar (Anil Kapoor). With a little help from Seema (Meenakshi Sheshadri), Amar teaches his family a lesson, and the ever-forgiving saint of a bhabi lives happily ever after with the rest of the family as well as newly-married couple, Amar and Seema.

At the same time, it is important to note the value that is attached to the sanskari bahu/bhabi, in some of the films - she is like a guardian angel to the devar and the rest of the younger members even, especially Uma in Sansar (T. Rama Rao, 1987), so much so that the entire family goes with her decision.

Dowry, a recurring topic in most of the films, is denounced in the narratives, but it acknowledges the prevailing practice in society. The concern for a bride to bring in dowry is attached to the class she belongs to. In films such as Biwi Ho Toh Aisi (J.K. Bihari, 1988) Rekha’s character marries rich without dowry, despite not belonging to the upper class herself, and meets with ill treatment from her mother-in-law (Bindu). The twist in the story is revealed when her character turns out to be an Oxford alumnus and was in cahoots with father-in-law (Kader Khan) to straighten her mother-in-law out.

When it comes to the genre, T. Rama Rao’s Sansar is one of the stand-out films in terms of the narrative and the interesting plot-points. An argument over finances occur between Vijay (Raj Babbar) the eldest son and his father Deendayal (Anupam Kher). Their argument separates the family while living under the same roof. Vijay’s wife Uma (Rekha) manages to reconcile the family with the help of other members. In the sub-plot, Rajni (Archana Joglekar), the daughter of the house, also causes tension in the family by going against her father to marry her Christian lover (Shekhar Suman). The happy ending that Sansar serves its audience is one of coming to terms with the changing times - Uma and Vijay decide to move out of the household as it is better to maintain harmony in the relationship while living separately than to bicker and hold grudges under the same roof. The anxiety of the disintegrating family stems from losing the Hindu moral values the family structure inculcates and propagates in society. Clearly a hierarchical structure of power, the traditions of upper caste Hindus are safeguarded within the joint family system. In response to the lack of representation of other communities in the genre, emerged the Muslim Social. It replicated similar tropes of family dramas, except within a world created with markers that are distinctly associated with Islamic culture and only Muslim characters. The patriarchal and hierarchical system existed within the Muslim social too, where the women were at the mercy of the men in her life.

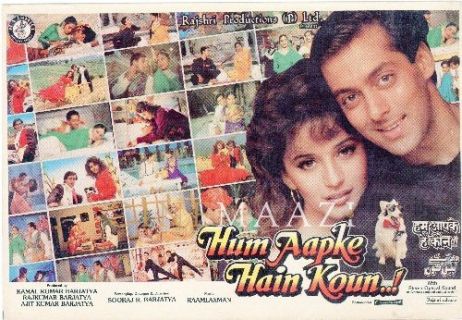

In his 1994 Hum Aapke Hain Koun...!, a film that documents upper caste North Indian wedding rituals elaborately, as well as an excessive depiction of wealth. This film was well received by audiences beyond prediction, as it brought back the middle class to cinema halls after the boom in VCR drove them to their homes for a period. The superstardom of Madhuri Dixit and the resurgence of Salman Khan, their jeans-clad modernity, the countless rituals and ceremonies, and the elaborate song and dance sequences also appealed to the nostalgic crowd of NRIs for whom it represented a connection to their homeland. The humongous success of the film proved the continued relevance of the family drama tropes. Another film that cannot be missed in the discussion of family dramas is Barjatya’s Hum Saath Saath Hain (1999). A modern retelling of the ‘Ramayana’, Hum Saath Saath Hain navigates filial love, brotherhood as the family navigates inheritance through sacrifices.

Apart from the spectacle of wealth in the film, one can also see individuality, to a certain extent, attached to Rahul’s character. Yet, the tradition that is crucial to the crux of the plot, which puts the parents on a god-like pedestal, requires him to not just reunite with the family, but also retain a hierarchical power in his household in London. Rahul as a patriarch of the household like his father is mostly relaxed except with his sister-in-law Pooja’s (Kareena Kapoor Khan) clothing choices. The women will always be governed by the male patriarch to regulate their ethical conduct in society.

In both the films, the special status of the adopted child highlights the primary status blood relation takes in upholding the so-called Hindu family values. It is implicit that blood relations supersede alternative forms of constituting a family. LGBTQ+ discourse has shown us different forms of families with individuals that are not blood related but form on the basis of a support system, yet the assumed legal papers deny the adopted characters in these films the inclusivity of a family. (It is interesting to note that Karan Johar is now himself a father to two children conceived through surrogacy.)

A recurring thematic element which appears throughout these films is the representation of the upper caste, upper class Hindu family. Apart from a few, such as Piya Ke Ghar and Sansar, a majority of the families live in lavish houses, which doesn’t suffocate their personal space which can be very likely in a joint family.

The couple, a main ingredient of the family drama, is depicted differently in comparison with other romance films. Of course, amidst all these family dramas, from the beginning lies the romantic love story of the couples. But what's interesting is, the couple is consumed within the family system in these films. Take for instance, Hum Aapke Hain Koun...! where Rajesh (Monish Bahl) and Pooja’s (Renuka Shahane) union was a blend of arranged cum love marriage - a perfect middle ground achieved by the film. After Pooja’s death, Nisha almost gets married to Rajesh sacrificing her love for Prem is the epitome of how the couple’s romance carries the shadow of the family.

While most of the coital couples in family dramas have had arranged marriages, and their relationship is seen through the lenses of a household and influences of other members, post liberalisation film characters have love marriages. The tiny jump from arranged to love marriage was directly connected to the power dynamics within the family and the shift in moral values. The women in these films are the binding force in the family while also playing one half of the romantic pair. Usually associated with the compromising, understanding and forgiving leading lady, Karan Johar changes the game with Kabhi Alvida Naa Kehna (2006). Although it’s not classified as a family drama immediately, one can claim to see it within the same category for a couple of reasons. Firstly, the film deals with Dev (Shah Rukh Khan) and Maya's (Rani Mukherjee) adulterous relationship, in which their families are entangled. Both Dev and Maya's spouses-- Rhea (Preeti Zinta) and Rishi (Abhishek Bachchan) - also collaborate professionally. There's an overcast of the other family members - spouses, children, parent and in-laws in their relationship throughout their romance.

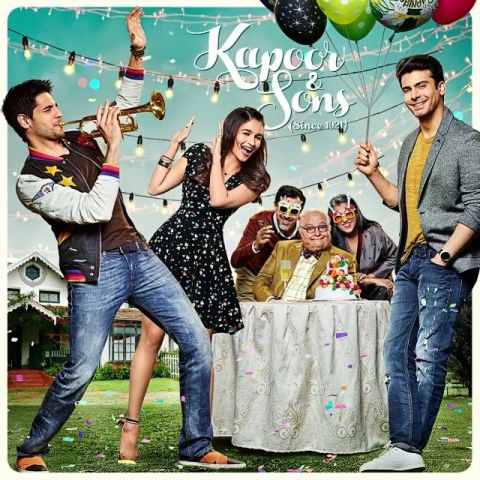

The trend of family dramas in mainstream Hindi cinema has continued with more or less the same anchor to hold onto - an upper caste North Indian family. But there have been changes too, the shift in focus in terms of class is interesting to note, with a lot of new family dramas based on the middle class. A lot of them wouldn’t be put under the category of family drama but instead romance, but genre is anything but rigid, and always an evolving idea. In Kapoor & Sons (Shakun Batra, 2016) the story of a dysfunctional family has an allegiance to similar elements from the older generation of family drama, but is made in a different model. The suspicions of the mother (Ratna Pathak) of an adulterous father (Rajat Kapoor) creates a lot of hair-splitting coupled with the underlying conflict between the two brothers (Fawad Khan and Siddharth Malhotra). The model of the joint family has changed, but carries forward a strain of the similar elements of drama. With the recent release of Shubh Mangal Zyada Saavdhan (2020) that navigates a homosexual couple’s acceptance by the family –especially the patriarchs. It is apparent from this that societal ethics is still mediated through earlier familial codes, although the fractures in them grow more perceptible every day.

.jpg)