Realism in Parallel Cinema

Subscribe to read full article

This section is for paid subscribers only. Our subscription is only $37/- for one full year.

You get unlimited access to all paid section and features on the website with this subscription.

Not ready for a full subscription?

You can access this article for $2, and have it saved to your account for one year.

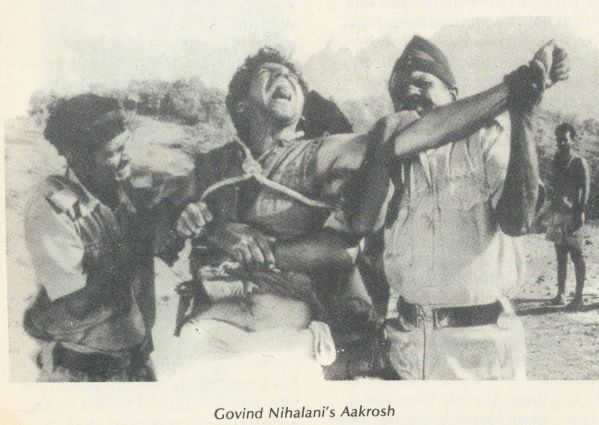

A prolonged lull on the Western film scene has been broken by Mani Kaul with his recent film Dhrupad (1983). The lull lingered for two years during which we saw an unusually insistent demand for attention from the Marathi cinema, and particularly raucous chest-thumping by the multi-crore commercial film industry. It resulted in greater emphasis on 'realism' in our art cinema if such a term may now be used for it, than and in the past.

Kaul's camera has now achieved a significance in almost everything he does. Whether in its stillness, capturing the soft textures of light and surface, or launching into majestic movement as in Dhrupad where it encircles the narrator it has grown to a point where it can draw from the very materiality of its object a larger sensuous world-view. In its simplicity of structure—a hard-won simplicity—it flies directly in the face of the gradually hardening conventions of realism that have come to define the genre of the 'non-commercial' film.

Kaul's work achieves particular significance because of the nature—and the strength—of the tradition that he confronts. Bombay, where he works, has since Independence, been the breeding ground of our national mass-culture, from where the mass-media radiate their hold over,the rest of the country. The big budget commercial film industry has been facing greater insecurity than ever before, and has been responding in the only way it knows how—to think bigger, more violent and more cacophonous than ever before. Its conventions have gradually hardened into inflexible laws. Its heroic figures straddle the entire screen. Its incessant bombardment of the senses has grown in intensity, its budgets have reached astronomical heights. Where G.P Sippy's Sholay released in 1975 drew gasps because of its extravagance of scale (an estimated 15 million rupees), today even a medium-scale film like Star (1982) has cost its producer Biddu, 10 million rupees.

Partly as a reaction is the emergence of another trend- the safe, middle of the road cinema. Films like Chakra (1981) have done for the industry what Love Story and The Graduate did for Hollywood—except that Chakra carries with it the 'art' label as well. This alternative genre is the realist one, offering an entirely viable "alternate" formula to the commercial film maker, and also raising enticing possibilities of foreign recognition.

Thirty years after the West has put realist preoccupations behind it, the Indian film maker is still considered somehow progressive if he works in the realist vein.

All the three Marathi films that claim our attention in the last year have been realist in this sense Amol Palekar's Akriet (1981), Bhaskar Chandavarkar's Atyachar (1982) and Jabbar Patel's Umbartha (1982). All three follow the dominant realist pattern of restricting the form to the dramatic level, never attempting the lyricism with which Satyajit Ray lifts it to significance. And all three reflect the manner in which the form, in playing upon predominantly middleclass sentiments, draws from other popular middle-class traditions of music, narrative and acting.

Their work, as indeed the work of most other realist film makers, is distinguished by the subjects they tackle. This is a phenomenon they share with all realism. As Raymond Williams points out, at its latter phase in all the arts, "realism was,....used to describe subjects and attitudes to subjects" (Raymond Williams "The Long Revolution", p. 301). The subjects here are feudalism and caste relations in the countryside (Akriet) the Working Woman (Umbartha) and the Dalit (downtrodden) class searching for self-respect (Atyachar) Their wide acceptability as progressive themes and the broad liberalism of position taken by the film makers themselves is particularly evident, for instance, in Atyachar which is based on the autobiography of one of our finest Dalit writers.

The raw power of the book and its sustained attack on the conservatism of the middle-class has been largely toned down in the film, and substituted for the more acceptable expressionist style of acting that passes for passion and anger.

What is, of course, interesting is that all the three film makers are from the stage, where they admitted no such realist barriers to their form. Palekar and Patel have been at the forefront of the tremendous leap that the Marathi theatre took in the early seventies , Bhaskar Chandavarkar was the man who provided the music for Patel's Ghashiram Kotwal (1976). The originality of structure that one saw in their theatre, evaporates in the cinema. It is a continuing tale. Sai Paranjpye, when she came to the cinema from the theatre and television, attempted a low-key realism in Sparsh (1980), then enlarged it to what is her metier, the light comedy in Chashme Buddoor (1981) and Katha (1982). Basu Chatterjee too started with the middle-class hero in Rajnigandha (1974) and developed it to one of the most successful formulae in the Hindi cinema today.

The more vigorous, explicitly political Shyam Benegal of Ankur (1974), while speaking about his most recent film has himself drawn a comparison with the Basu Chatterjee style of comedy claiming that his has the larger canvas.

Two years ago, Ketan Mehta had completed his Bhavni Bhavai (1980), Saeed Akhtar Mirza his Albert Pinto Ko Gussa Kyon Aata Hai (1980) and Mani Kaul his portrait of Gajanan Madhav Muktibodh in his Satah Se Uthata Admi (1980) and one had felt then that the abortive breakthrough of the early seventies with the Film Finance Corporation-sponsored cinema had once more come to the fore with these films. Since then, these film makers have not been able to work- their absence from the scene has coincided with a swiftly changing socio-political milieu with increasing emphasis on the individual , the charismatic—romantic beliefs permissible only in a one-way communication to the audience, and the corresponding sensory domination of the masses'. Mehta's journey from the folk to the documentary, Mirza's extended shots that break through heroic facades or Kaul's stylisation of light and volume, these release the viewer from the bondage of his senses. This is the only significant tradition we have in the cinema, the tradition one hopes may resurge with Dhrupad.

This article was originally published in Indian Cinema'82/83. The images used in the feature are taken from the original article.

Tags

About the Author

.jpg)