The Most Enduring Matinee Idol: Mahanayak Uttam Kumar

Like the commercial cinema of any region, Bengali cinema as well was never short of its stars since inception. The first genuine star was the inimitable actor-director Pramathes Barua whose tragedy-inflicted Devdas (1935) had an entire generation lilt to the pain of an escapist suitor. There was also Dheeraj Bhattcharya with his aristocratic looks or Asit Baran with his humble next-door-boy image.

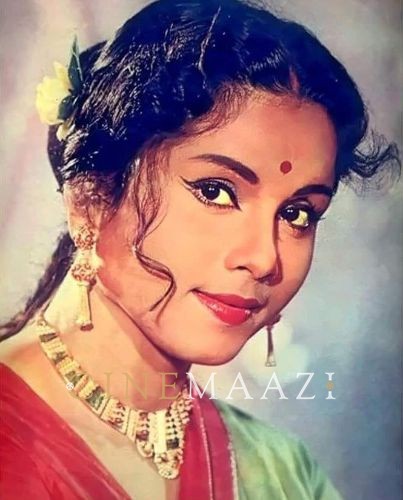

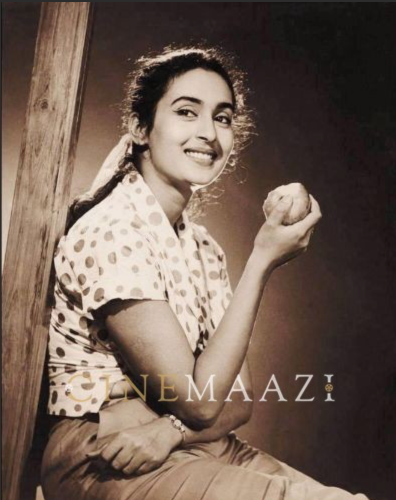

In the 1950s came Basanta Chowdhury, Nirmal Kumar and Anil Chatterjee – all of them marked with good looks and excellent acting to support their screen presence. In 1959 Soumitra Chatterjee debuted in Satyajit Ray’s third part of the Apu Trilogy – Apur Sansar (The World of Apu) and remained in the heart of Bengali and international film audience with his plethora of stupendous histrionic. However, the first superstar and probably the most enduring matinee idol of Bengali cinema till date is bestowed on none-other-than Uttam Kumar – the true and only ‘maha-nayak’ of the Bengali entertainment industry.

Arguably, in the three decades from the 1950s till death in 1980, Uttam Kumar acted in approximately 200 films; over 150 were hits making profits above the average. Uttam’s first released film was Drishtidan (1948) directed by legendary director Nitin Bose though he acted in Mayador before this which was never released.

After a string of flops, his first major hit came with Basu Paribar in 1952. In the following year with Saare Chuattor history was made in the Bengali film industry. It was a wholesome entertaining film and is recognised as an iconic comedy film on the Bengali screen. The elder pair of Tulsi Chakraborty and Malina Debi stole the show along with cameos from Bhanu Banerjee, Jahar Ray and others. Uttam and Suchitra rather made an impish entry for the first time as the romantic pair – not unnoticed but definitely not making much of an impact as well. The duo, however, did set the Bengali screen on fire till the rest of the decade of the 1950s with 20 films together. Along with them, they took stardom to dizzy heights that no other romantic on-screen Bengali pair-matched ever with the films like Sagaraika (1956), Sapmochan (1955), Sabar Uporey (1955), Shilpi (1956), Harano Sur (1957), Pathe Holo Deri (1957), Jiban Trishna (1957), Indrani (1958), Chawa Pawa to name some.

At the heart of most of these films is the Nehruvian ideal of a nuclear family for modern India where the village boy finds settlement in the urban Indian city. It is his journey towards the exterior, leaving the comforts of his joint family in the village. In this, he finds an able partner in the form of a girl-friend who ascends to a wife to wade off the struggles and difficulties imposed on them by the society at large.

This self-reliant couplet represented the modern India of the 1950’s – a dream for many migrant Bengali men who had to leave their birthplace in East Bengal, now Bangladesh in search of a fortune in the city of Calcutta. Uttam Kumar represented that dream of a migrant nation, romantic in vision yet timid with a fear of an uncertain future – but, forever smiling. Uttam Kumar had a unique smiling quotient. It would make him look like a warm son, a loving elder brother and most importantly an unflinching romantic partner. Even with moderate looks, this smile won him hearts – “Uttam Da had used it as his lethal weapon, he knew it works and used it profusely without making it look too commonplace” quipped Soumitra Chatterjee, his compatriot. And most of these films had scintillating songs – Hemanta Kumar Mukherjee playing back for Uttam Kumar and Sandhya Mukherjee for Suchitra Sen, a chemistry that was no less important to make their films super hits.

The magnum success of the 1950s as a romantic pair had an interesting turn in the following decade as they acted together in only 4 films and the same number in the 1970s. The major hit during this time is Saptapadi (1961) which also remains one of their all-time biggest hits.

Uttam Kumar gives a fine performance in Satyajit Ray's masterpiece Nayak where he plays the character of a matinee star.

Both Suchitra and Uttam drifted apart and made films with other screen partners yet garnering hits by their own rights. Uttam’s greatest moment of acting revelry came in 1966 with maestro Satyajit Ray’s Nayak which the ace director admitted was written keeping a star as big as Uttam in mind. After Uttam’s demise Ray paid his tribute in no uncertain terms – “There isn’t – there won’t be another hero like him”. Nayak put Uttam Kumar on the pedestal of a cerebral actor and film critics and scholars started taking Uttam more seriously than just a romantic hero. Ray followed Nayak up with Chiriakhana (1967) where Uttam played Byomkesh, the sleuth – a film which neither got critical acclaim nor could warm up the box-office sales.

In the same year Uttam played Anthony Kabiyal in the film Anthony Firingi, an acting masterpiece which along with his histrionic in Chiriyakhana fetched him the Best Actor award (named as the Bharat Award at that time) at the National Film Awards, India.

Uttam Kumar assumed the role of the big-brother of the industry onto him and helped needy technicians and members of the crew. This personal trait did make Uttam special to most of his co-stars and compatriots. For the non-Bengali audience he was the epitome of a perfect Bengali as Rajesh Khanna observed – “Uttam Kumar as the Bengali babu is unique. What I believe is that there is no one who can ever represent the Bengali community like Uttam-da did.”

Apart from Ray, neither Ritwik Ghatak nor Mrinal Sen (apart from his first feature film, Raat Bhore, in 1955 where he had Uttam Kumar in the lead) thought of using Uttam – a rare misfortune of Uttam and of the audience. However, the other great director who exploited Uttam’s histrionic ability and expanded his acting horizon was Tapan Sinha. Sinha casted Uttam in Jhinder Bandi (1961) and Jatugriha (1964) – both markedly different in style, genre and content. While the former is a successful adaptation of the epic The Prisoner of Zenda, the latter is a short story of an urban couple not in terms with each other. Sinha mentioned, “I personally felt that the acting of Uttam Kumar could be compared to the best actor of any country. His great attribute is his diligence…Many are born with talent, but the talent gets eclipsed due to the lack of diligence. Uttam Kumar has both of them. Perhaps, that is the reason why he still sparkles.”

.jpeg)

As the 1960s drifted to its end, the political crises in the country and the turbulent streets of Bengal didn’t see much reflection in the Bengali screen apart from sporadic attempts to represent the reality of the times. Uttam Kumar, however, shifted to a slightly different sort of role given his matured age by then. The unsure, introverted man with boyish charm as in the films of the early ‘50s got changed to a confident, arrogant and smart individual in many of the films during this time. Three films that do need special mention are Aparichito (1969), Stree (1972) and Sanyasi Raja (1975).

In all of them, Uttam would play the role of a temperamental rich humbug drowned in vices. The 1970s also witnessed Uttam’s penchant for comedy acting in Dhanni Meye (1971), Chadmabeshi (1971) and Mouchak (1975). Some other films of the same decade where Uttam played character roles but with aplomb are Nishipadma (1970), Agniswar (1975), Bagh Bandi Khela (1975) and Sabyasachi (1977). Apart from Bengali, Uttam Kumar also acted in some Hindi films viz. Chhoti Si Mulaqat (1967), Amanush (1975) and Anand Ashram (1977) though his foray into Hindi films remained unsuccessful as a whole.

Uttam Kumar passed away on 24 July 1980 at the age of 53 due to a heart attack which he suffered during the shooting of Ogo Badhu Sundari (1981). When he was alive and 35 years since his demise, there is no Bengali actor who could match his stardom. In the popular Bengali mass media space the successor of Uttam as an icon is not an actor, but the cricketing legend Sourav Ganguly. Like Sourav, Uttam as well-shaped his own destiny, been ruthless in his conquers and ultimately representing a mass of people who themselves prefer to be far less dynamic than these demigods.

Today, the young generation finds it difficult to relate with Uttam Kumar or his films. Playing a quiz on Bengal’s most prominent film star can at times becomes dangerous and certainly preposterous. For a teenager, even in Kolkata, the name now means a metro station, a theatre hall and well maybe a film star – at least that was my reality in a newly cropped up media college at the heart of the city. Granted, most of the students are Hindi speaking, many from outside Bengal as well, however even those who are Bengalis, born and brought up here, the shadow of Bengal’s lone matinee idol isn’t long enough to cover their virgin heads. ‘Oh the black and white films are so awful, so slow, no action, boring’ they would chirp. For them life is fast, about android apps and apple iTunes, it is about Hindi demigods and in disowning a vernacular identity. For them, who all are born in the later part of the 90s, the imprint of a collective nostalgia imbibed from their parents is probably of the 1980’s when their parents were young and romantic.

Soon after his passing away the Bengali film industry was swept by a surge of remakes from Hindi and South Indian films (at least both Tamil and Telegu). Hence to hold on to nostalgia of a golden period of Bengali cinema when he thrived (in the 1960s and 1970s) is probably confined to the Bengalis who are in their mid-life – either at home or in the outer world as well.

The mainstream Bengali media prevalently serves an audience dipped in the nostal-sauce which suits both the consumer and the producer. Increasingly, in the heart of the state capital, Hindi language is gaining prominence as the ‘more important’ language to learn and communicate with – no surprise that the Bengali language is at stake. The risk that lies here is while the bastions of culture try to uphold the golden periods of yester-decades without necessarily understanding that this may distance the young even further if not packaged sufficiently well.

.jpeg/WhatsApp%20Image%202020-12-21%20at%2016_03_57%20(2)__600x380.jpeg)

The middle-aged Bengali who has moved shores to relax on a Pacific coast or a Mediterranean retreat or the one who decides that for his/her next generation Bengali is essentially a ‘third’ language, the nostalgia of this Bengali-ness is flaring. It will remain their favourite pastime to chew on, to ogle at Uttam Kumar’s films and to marvel at his charisma as a romantic hero draped in the traditional dhoti and Punjabi.

The ‘box-office phenomenon’ of Uttam Kumar may die its own death slowly if it can’t be preserved in its true essence and the culture doesn’t support it favourably. What will, however, survive probably, are the character roles that he played in the films of Tapan Sinha, Satyajit Ray and a few other directors. They will remain for an academic interest with the film scholars and those who will want to identify with the pathos of a bygone era. This is where he transcends the tides of time and becomes a legend.

This article was originally published in Silhouette magazine on 24 July, 2015. The images used in the feature are not part of the original article and is taken from Cinemaazi archive and the internet.

Tags

About the Author

Amitava Nag is an independent film critic and editor of film magazine 'Silhouette' (www.silhouette-magazine.com) since 2001. Till date Amitava has authored 5 books on cinema including 'Satyajit Ray's Heroes and Heroines', '16 Frames' and 'Beyond Apu: 20 Favourite Films of Soumitra Chatterjee'. Amitava also writes poems and short fiction in Bengali and English and authored a collection of short stories each in English and Bengali, and an anthology of Bengali poems.His first anthology of English verses and a selected translation of Soumitra Chatterjee's poems are awaiting publication.

.jpg)