In Defence of Sexuality: The '90s

What is the most popular myth about Hindi cinema? The one that insists that popular mainstream films treat their women as the 'side-hero' and relegate her to the traditional second sex status. Of course, there has been a surfeit of the weeping willow image in the garb of the sacrificial mother, the silly sister who invariably looms up as the potential rape victim, the villain's woolly-headed moll or the towering inferno's glamourous appendage. And the independent woman has largely surfaced as the female Bachchan clone: an aggressive avenging angel who is hell-bent on salvaging her outraged honour through guns and guile. Needless to say, this scorned fury is invariably cast in the mould of a Zakhmee Aurat (1988) or a Daku Hasina (1987).

But that is just the inglorious past. Cinema of the '90s might have a million 'firsts' to boast of. However, more than the genesis of the Khalnayak (anti-hero) as the Nayak (hero), contemporary Hindi films stand out for their changing perspective on the prototypal celluloid woman.

Yes, the Hindi Film heroine has finally emerged from the shadows. No longer a svelte second-hander who stands by for the traditional macho act, she is setting the pace, defining relationships and brazenly defying the questionable tag of all-body-no-brain that had clung to her. Today she may still be running round trees in multi-coloured micro-minis, waiting for Prince Charmings and Ramboesque Robin Hoods. But no longer as a gullible little Red Riding Hood who can be swept off her feet by the first smart cookie. Or one who might easily fall for the wily charms of the big bad wolf. No, she knows how to protect herself, rarely prostrates herself and almost always asserts herself as a heady mix of body and brain.

Suddenly, the image has lost its linear proportions. The heroine is no longer content to rest as the hero's accomodating moll. Even if she does, it has to be as the aggressively demanding, sexually assertive girlfriend. Now an avenging angel (Khalnaika (1993) and Anjaam (1994)) who is determined to do away with anyone who dared to tamper with her state of well-being, she is transformed into the traditional housewife (Damini (1993), Saajan ka Ghar (1994)) with equal ease. And when she's not looking after kith and kin, she's looking after the greatest good of the greatest number, a la Tejasvani (1994).

Karisma Kapoor's rise to success was synchronised with the popularity of the new modern women in Hindi cinema. Earlier, it would have been an unusual choice for the lead heroine instead of the 'other women', to dance to a song like Sexy sexy mujhe bole was possible in the 90s.

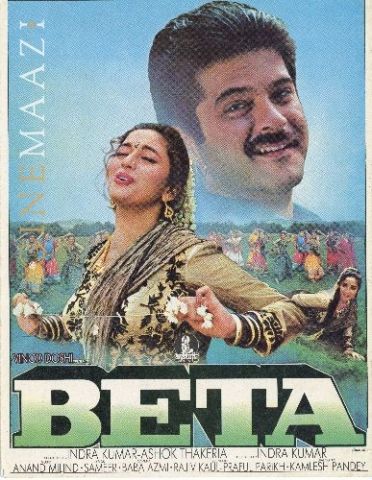

Unlike her Hollywood counterparts, this tantalising blend of intelligence and erotica makes for neither a Sharon Stone nor a Madonna who uses her physicality for libidinal causes alone. For that flavour of Indianness, native filmmakers have intelligently added a suffix to all the sensual display. Interestingly, all these characters have a noble cause behind their allegedly ignoble acts. There was a sacrosanct motive behind the controversial 'choli ke peechey' number itself. Madhuri Dixit throws off her constable's attire and dons the itsy-bitsy choli - blouse in order to seduce the terrorist and bring him back to the hallowed portals of law. Simply because this would salvage the honour of her man, the Inspector Rama (Jackie Shroff), which had been jeopardised by the Khalnayak's jailbreak. "Main apne Rama ki maryada ke liye kuch bhi kar sakti hoon," (I can do anything to uphold the honour of my Rama), she declares and enters the Khalnayak's lair with her seductive act.

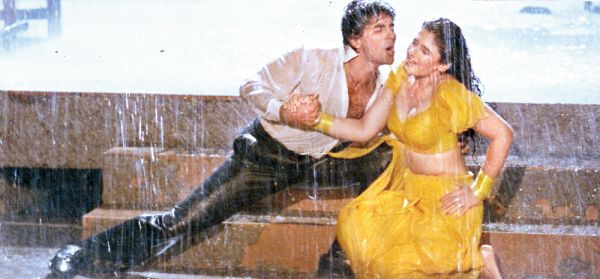

Then, in Khuddar, the infamous 'sexy-sexy-sexy' number (later changed to baby-baby-baby) may have Karisma Kapoor brazenly wriggling her derriere before the camera. But here too, the filmmaker has ingeniously furnished a philanthropic motive to this saucy show. "I show off my thigh so that their legs may remain strong and covered," she fiercely declares to the dismissive cop who scoffs at her streetwalker ways. The scornfully departing inspector turns back, and lo! There beneath the fluttering tri-colour, she stands: the short-skirted floor-show girl, clustered around by her brood of hungry, half-clad orphans who have no one but 'didi' (elder sister) for succour. Naturally, the hard-boiled cynic is transformed into an awe-stricken admirer, who ends up equating this 'Bharat ki beti' (daughter of India) with the Bhagavad Gita.

"Tum mein bhi ek Mahabharat hai" (There is a Mahabharat in you too), he declares and reverentially kisses her hands, scorn obviously replaced by devotion. And, now, for the rest of the film, this brazen girl, who almost ended up as the star of a blue film (against her wishes, of course), plays a demure, sari clad, sightless wife who doesn't step out of her husband's house.

It's a mindboggling mix of tradition and modernity that our filmmakers seem to have achieved of late. The emphasis of course is on 'Indianness.' as opposed to absolute 'westernisation'. And a perfect prototype of this modern Indian woman one who is neither all-Indian nor all-western-can be found in Sooraj R. Barjatya's Maine Pyar Kiya (1989) and Hum Aapke Hain Koun...! (1994) Both Bhagyashree in MPK and Madhuri Dixit in HAHK are god-fearing girls, adept in Indian dance and music, in shelling peas, frying pakoras, chopping vegetables, feeding the family and looking after kith and kin. All this, despite their education (Bhagyashree completed her Intermediate and Madhuri's a graduate in computers) and their 'westernised' sartorial sense and completely urbane look.

But unlike the Victorian visage of the ‘50s, '60s and '70s, tradition here does not stand as a synonym for submissiveness. No, not even unwarranted coyness. For, Bhagyshree, who even closes her eyes when her beau offers to rub a dash of lodex on her sprained ankle, sets aside all false modesty and serenades in a bare-all evening dress before him. Simply as an expression of her intense love. Juhi Chawla does it again in Raju Ban Gaya Gentleman (1992), despite being a 'Propah' bustee belle with the characteristic set of middle class morals. This time, for her sweet little Raju, who has finally managed to fulful his dreams in the big bad city of Bombay. Needless to say, this partial abeyance of maidenly modesty is for love alone.

The familiar stereotype of the dumb belle is gradually being corroded, even in the traditional image of the woman in love. Narrative fiction, be it the novel, cinema or drama, has usually painted the woman in love as the vulnerable waif, the damsel in distress or the sacrificial wailer. The contemporary film heroine, however, seems to have a head over her shoulders, even in these wailing parts.

Soon, she becomes a fashion model who is all set to sail the high seas. Again, a new angle to the Cinderella myth, where cinder's girl looks beyond Prince Charming and his white steed.

Main duniya bhula doonga was a popular song from Aashiqui (1990)

Anu is no exception to the rule. In all the immensely popular love stories of recent years (Dil (1990), Qayamat Se Qayamat Tak (1988), Tezaab (1988)), the women are equal partners in rebellion. For, here, love is no roses or moonlight make-believe. Instead, it is a revolt against authority, class and caste barriers, destiny and the like. And if the hero is on the run, he has the heroine by his turbulent side all through the two-person uprising, matching his guts, guile and gore.

The power of the traditional woman manifests itself in its full glory in Raj Kumar Santoshi's Damini. A simple, god-fearing woman, who would have been happy to lead her life within the confines of her husband's house, Damini (Meenakshi Seshadri) suddenly decides to forgo everything for the sake of her principles. She is willing to place everything her husband, her home and her family's reputation at stake, so that truth and justice might prevail. Even a moist-eyed Juhi Chawla in Saajan Ka Ghar often manages to make a few pointed digs about the second-sex stigma that a conventional woman often endures as a daughter, a wife and a bahu (daughter-in-law).

The positive woman-as-crusader image that manifested itself in N. Chandra's Pratighaat (1987) reaches fruition in Tejasvani, his remake of the Telegu hit Karthavyam (1990). Obviously inspired by the exploits of the famous police officer Kiran Bedi, the film has reportedly inspired thousands of girls in Andhra Pradesh to join the police force. In a traditionally male-oriented society, Tejasvani is the small town girl who declares that her hands are not made to knead the dough or wash utensils alone. Instead, they have the power to procure justice for the meek. Tejasvani is the supercop who refuses to give up the battle against injustice, oppression and crime, despite the pressures of the family, of the administration and the mafia. No, she refuses to break down even when the bad guys try to turn her into a physical wreck. Somewhere along with her gritty strong-arm tactics, she deals a crumbling blow on the defenceless damsel-in-distress screen image of the Indian woman.

The song Dhik ta na na from Laadla exemplifies the westernised, independent women before donning the traditional sanskari wife transformation in the film.

"Please come home early in the evening." Needless to say, the husband has now moved from the ranks of the blue-collar to a white-collar status: he is now the owner-manager of the company. Laadla thus revives the accepted gender balance once again: the man brings in the moolah and attends to all the business outdoors, while the woman manages the home indoors.

Nevertheless, a metamorphosis is there to see. The changing facets of the woman's face signify the beginning of a heartening trend: the Hindi film heroine has finally walked out of her strait-jacket. No longer is she merely willing to remain the wind beneath the hero's wings.

This article was originally published in the Indian Cinema 1994 issue. The images and video used in the feature are taken from Cinemaazi archive and the internet

.jpg)