Commercial Cinema: Zeroes As Heroes

There was a time when the Hindi film hero had to be larger than life. That was in the '70s and '80s when the angry young man towered above the teeming millions, trying to wage a lone battle against smugglers and racketeers.

Today, the '90s have bid adieu to the superstar phenomenon, both on and off screen. In the current lexicon there is a refreshing inversion where smaller becomes larger and zeroes become heroes.

Behind the screen, the road to stardom is presently overcrowded with a brat-pack where no single name dominates the marquee. It's a multi-layered hierarchy where the numbers game keeps throwing up new names, new faces, even as the older ones slip and trip over the box office. Hence, this is an age when viewers can watch Mithun Chakraborty mumble on one screen, and Mukul Dev sashay with Sushmita Sen on the other. Not forgetting a tryst with Shah Rukh Khan, Salman Khan, Akshay Kumar, Sunil Shetty or Nana Patekar, in between. Or maybe, Madhuri Dixit do the jig in a Prem Granth (1996) and Priya Gill play a pretty Tamilian in Tere Mere Sapne (1996). In this newly-established democracy in Bollywood, newcomers never had it so good. Undoubtedly, the '90s has been a decade of discoveries, some successful, some insignificant. Nevertheless, all making a bid for stardom. Chandrachur Singh, Arshad Warsi, Sharad Kapoor, Mukul Dev, Bobby Deol, Saif Ali Khan, Mamta Kulkarni, Kajol, Kamal Sadanah, Akshay Kumar, Sunil Shetty and Shah Rukh Khan too: the billboard of popular mainstream has been spilling over with new names every year since the onset of the decade.

On screen too, it is the traditional loser who seems to be walking away with the accolades. In the Rangeela (1995) and Raja Hindustani (1996), Aamir Khan plays a fringe man: a hero who lives on the other side of opulence, success and overt grandeur. Nevertheless, he has an allure that outrivals the charisma of the rich and the famous. The qualifying mark of almost all the David Dhawan-Govinda blockbusters is the small, insignificant hero who has none of the grand traits of the traditional hero. Govinda in Coolie No. 1 (1995), Aankhen (1993) and Sajan Chale Sasural (1996) is essentially a man—any man—from the masses that throng the big and small cities. He not only dresses and speaks like the plebian but also dreams like them. Small man, small dreams big victories. This seems to be the sequence of events where despite his smallness, the hero manages to save the nation, clean up the city or win favours from the hands-off maiden. And everything without displaying super natural brains or brawn.

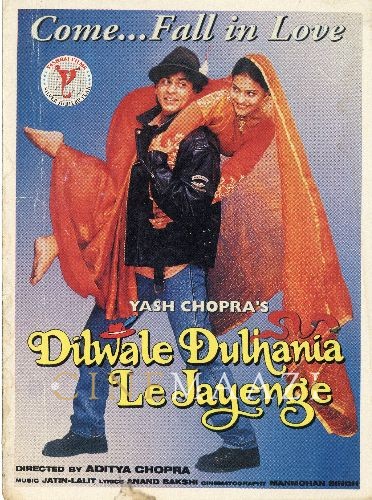

The success of Aditya Chopra's Dilwale Dulhaniya Le Jayenge (1995) can also be largely attributed to the fact that it unabashedly romanticised the 'loser' image, bringing to the fore a conformist hero. One who stood out despite his conformism. For Raj (Shah Rukh Khan), the hero of DDLJ is the antithesis of the larger-than-life rebel, the erstwhile hero of Bollywood mainstream.

Unlike the angry young lovers of the 1980s, perfected in films like Qayamat Se Qayamt Tak (1988), DiI (1990), Sadak (1991) and Baaghi (1990), Raj is neither angry nor rebellious. He is desperately in love with his dream girl, Simran (Kajol), but he does not want to tear the meddlesome world down or turn his back on it. Not even when it threatens to tear the lovers apart. This attitude stands out in stark contrast to the earlier behaviourial code, where rebellion was the first reaction to resistance, rituals, rules and customs. In DDLJ, parental opposition has an opposite reaction altogether. Instead of turning his back to familial discord, Raj longs for acceptance. The good, clean image is further compounded by the fact that the hero does not let go of his desire for compliance and conformism, even though the girl is willing to go against her father's wishes.

In a cinema where anger and rebellion have largely been the fulcrum around which the drama revolves, DDLJ's hero may seem anachronistic. Obviously, for this conformist, anarchy is a dead cult. Nevertheless, it is this intense reverence for accepted value systems which makes him a hero. The allure of this nineties hero can be traced to those old-fashioned values: respect for elders, obedience to the patriachal law and an overwhelming desire to belong to the fold, clan, community or tribe.

In such a scenario, vigilantism remains. But in a changed garb. The vigilante must be a man from the masses. Somebody who is quite different from the usual hero. The nineties do-gooder need not be a morally unblemished superman. On the contrary, the could be a conventional weakling or even a man of murky morals like Sanjay Dutt in Khalnayak (1993) and Nana Patekar in Krantiveer (1994). Or he could be the wrinkled septuagenarian of Shankar's Hindustani (1996) who launches a one man army against corruption and bribe, despite his apparent physical debility. Conventionally speaking, Senapathy (Kamal Haasan) should have stepped into the shadows of his green rice fields, after he had played his role in the freedom struggle. Instead, he returns with a knife that is meant to clean up the corrupt in a mission which for him is an extension of the freedom struggle.

The success of characters on the small screen, in serials like Swabhimaan, Karamati, Mewa Lal or even Hum Log also proves that what the audiences now want are not the diehard romantic superheroes of the last few decades, but someone they can identify with easily.

This new trend of the unconventional vigilante and the smaller-than-life hero becomes easy to understand in view of the increasing disillusionment of the common man with 'outside' deliverance. Neither the state nor a larger-than-life messiah can bring back order, equity and justice in their lives.

In a scenario lavishly sprinkled with scams, communalism and political corruption, where the needle of suspicion points towards the upper echelons, the ordinary citizen can turn to no one up there. For him, there can now be only someone like him: either a down and out loser, a traditionally immoral being, or a weak and seemingly puny soul to fuel his fantasy in the age when idols have fallen and superheroes are dead. The identification is complete.

This article was originally published in Indian Cinema 1996's issue. The images used in the feature are taken from the internet, Cinemaazi archive, and the original article.

.jpg)