Hemen Gupta: His Life and Times

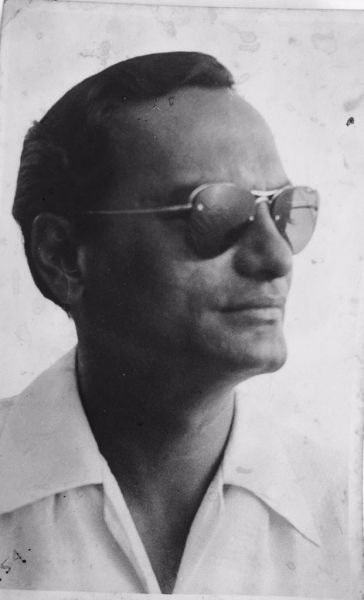

A freedom fighter who ‘almost went to the gallows twice’ for his revolutionary activities, Hemen Gupta was introduced to cinema by none other than Netaji Subhas Bose. Anirudha Bhattacharjee looks at the fascinating life and times of Hemen Gupta, acclaimed director of films like Anand Math and Kabuliwala

Prologue

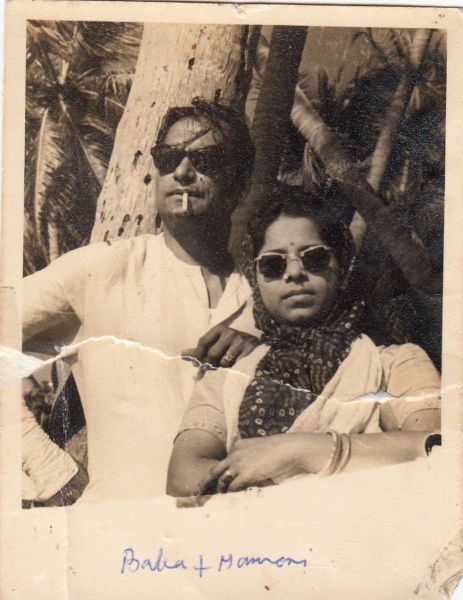

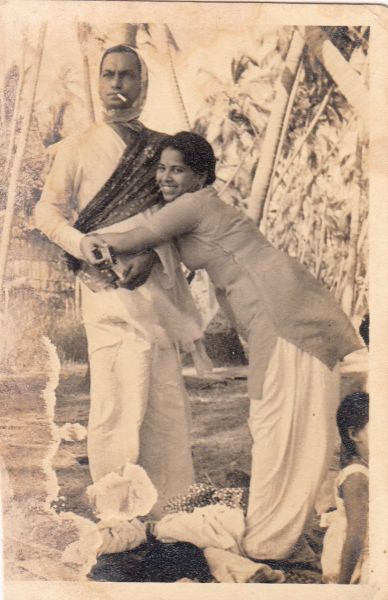

In the fall of 1957, a Bengali family on 15th Road, Khar, Bombay, put to test its latest buy – a steel-grey Plymouth Belvedere Convertible – on a road trip from Bombay to Calcutta. Not only was the trip via Rajasthan, Delhi, Allahabad and Varanasi unorthodox enough to leave even the eccentric bemused, it spoke of an adventurous streak not normally found in people associated with popular Hindi cinema, certainly not when travelling with family including children. In those days, not all river crossings had roads – the car had to be taken onto a boat, to cross the Kalpi in Madhya Pradesh; also the car had to be taken onto a railway carriage to cross the Sone in Bihar. A joyous fortnight at Russa road, Calcutta, followed the five-day trip. This break from the normal routine included viewings of the Goddess Durga in puja pandals across the city.

The family took a detour on the return journey and made an unscheduled stop at the place of Dr Biren Gupta at the Railway Colony near Hijli. A few kilometres away, in a place which looked like no-man’s land, was a huge building with a tower standing tall. As the head of the family took his son Jayanta to a tour inside the imposing façade, he remarked, ‘This, as you can see, is the prestigious Indian Institute of Technology, Kharagpur. In the 1930s, it was the Hijli detention camp. And I was locked up here for some time.’

Hijli jail was not the only one where he had been incarcerated. Hemen Gupta had served more than six years in prisons across the country, from Buxar in Bihar to Deoli in Rajasthan.

BBB, or B cube, is a colloquial term used in modern-day Bengal by a particular community. It translates to Barisal–Bangal–Baidyas, referring to East Bengalis of the Vaidya caste originally from Barisal district in present-day Bangladesh. The acronym can be interchanged with DBB, the D standing for Dacca. The affluence of places like Dacca and Barisal in pre-Independence India was partly due to the small but strong Bengali Vaidya community (some of them had also espoused Brahmoism, the non-ritualistic sect of Hinduism). Though the word ‘Vaidya’ translates to doctor, the average Vaidya community had doctors, lawyers, poets, educationists and freedom fighters. Gupta and its variants were the most popular surnames of the Bengali Baidyas, though there have been other surnames like Roy, Dutta Roy, Sarkar, as well. And versions like Jibananda Das(gupta) or Chittaranjan Das(gupta), from the clan of Barisal Baidyas and Dacca Baidyas respectively.

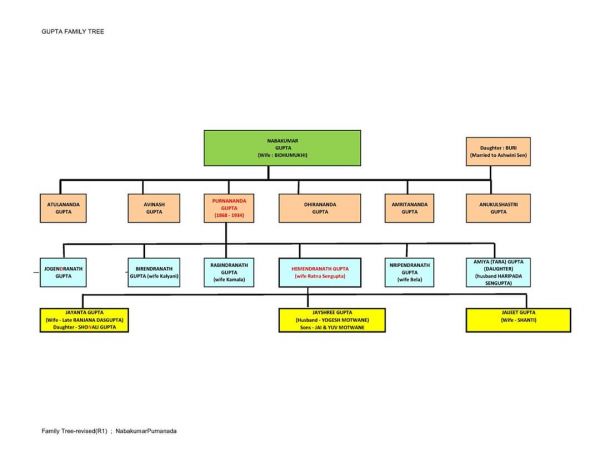

Nabakumar Gupta was one such prominent Baidya. The family was originally from Faridpur but had shifted to Dacca. Purnananda Gupta, his third child (some say second), was an officer in the British government state treasury. Hemendranath Gupta, Purnananda’s fourth son, was born on 21 March 1914 (the year is debatable, it is more likely around 1910–12) at Rajmahal, Bihar (present-day Jharkhand). The place of birth is gleaned from his interviews to Filmfare staff and to veteran editor T.M. Ramachandran of Sports and Pastime. Bengalis usually have a nickname, and young Hemen was addressed by the name Kanai. His younger brother Nripen was called Balai. Subsequently, Kanai got shortened to Kanu, and Balai to Bolu. Interestingly, the younger children called Hemen Misri-da (misri roughly translates to rock-sugar or rock-candy). His sister Tara used to be called Misri-di. Gradually, this name found acceptance in the next gen as well.

This prosperous joint family had members who would go on to become celebrated media persons later. One among them was film-maker Harisadhan Dasgupta, recalls Jayanta Gupta, son of Hemen Gupta. Film-maker, critic and historian Chidananda Dasgupta was married into the extended joint family.

Most of Hemen’s initial schooling was in Dacca. An extremely well-read, articulate and good student, Hemen was a firm believer in the adage ‘All work and no play makes Jack a dull boy’. While a student, he undertook a cycle trip to north India, travelling to Amritsar and nearby via the Grand Trunk Road. On his return journey, he was attacked by a wild boar in the jungles of Hazaribagh (in present-day Jharkhand). This left a deep and a permanent scar on his right thigh.

The family had huge tracts of land in and around the city, and a part of it was later leased for ninety-nine years for a school in Nabakumar’s name in 1916. In 1973, a college wing was added to the building. Nabakumar Institution remains a prominent school cum college in Dhaka even today.

There is an uncorroborated story that Purnananda Gupta had been transferred to Midnapore in the last part of his career, and his family went with him. It is not difficult to connect the dots given that many of Hemen’s elder brothers and cousins started working in and around Midnapore during the late 1920s and early 1930s, around the time when Purnananda retired from work (in 1928) and shifted to Calcutta. He settled down at Sardar Sankar Road near Lake Market, Calcutta. Film-maker Bimal Roy too stayed as a tenant at a modest house on the same road till 1951.

The Freedom Struggle

In 1928, Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose had started a revolutionary group named Bengal Volunteers. In Midnapore, the movement found great momentum with Dinesh Gupta becoming part of it. As a student in Midnapore College in 1927, he had already started training the local youth on the use of arms. All these culminated in the killing of District Magistrate James Peddy, ICS, in 1931. The story was repeated with the killing of Robert Douglas, ICS, in 1932.

Hemen’s anti-British stance translated into trouble for his father. He had to forfeit his pension. The family printing press had to be closed down. Purnananda, once a rich man used to a lavish lifestyle, passed away in 1934 for lack of proper medical treatment. He was sixty-six.

The early and the mid-twentieth century was a time when most educated Bengalis opted for government jobs. Manas Ranjan Gupta, son of Anukul Chandra Shastri (Nabakumar’s youngest son), was an employee of the treasury at Midnapore. As he was dealing with government money, a safety deposit of Rs 25,000 had to be made before the appointment letter was released. This was in the early 1930s. A government job was reason enough for a marriage to be arranged; and Manas Ranjan was at Dacca over a considerable period of time, attending to the post-marriage rituals.

Manas Gupta’s house – in his absence – was the meeting point of the local revolutionaries. The third killing, of District Magistrate Bernard E.J. Burge, ICS, was conceived there. Burge loved football, and it was the kick-off whistle for an exhibition match between Mohammedan Sporting of Calcutta and the Town Club of Midnapore at the Midnapore College ground which served as the signal. Burge, who blew the whistle, was shot. The date: 2 September 1933.

Most of the relatives of Manas Ranjan Gupta were under suspicion. Hemen Gupta, who had been singled out for seditious activities before, was arrested, though as Anuradha Gupta, daughter of Manas Ranjan Gupta, says, her Misri-kaku was not physically present at the ground. With the exception of Jogen Gupta, Hemen Gupta’s eldest brother, all his relatives who lived in and around Midnapore district lost their jobs within twenty-four hours. This included Hemen Gupta’s brother, Dr Biren Gupta, who was employed with the government as a dentist in the Kharagpur–Midnapore region.

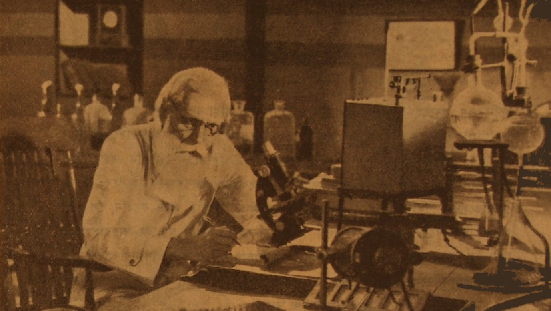

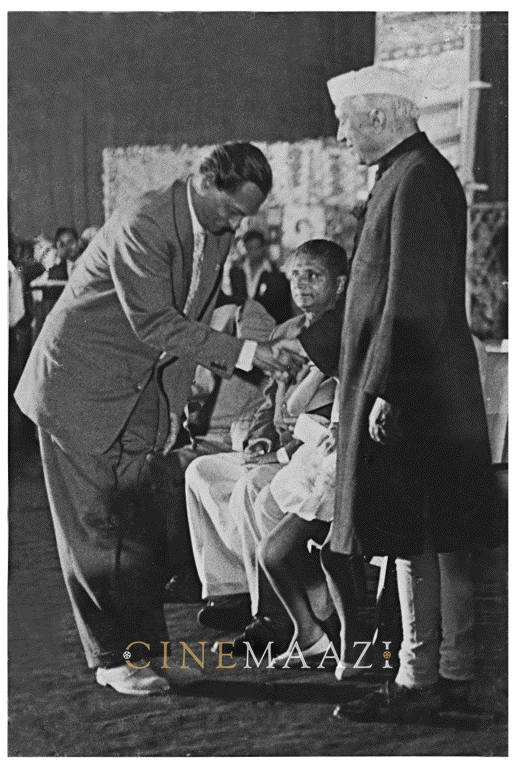

On his release from jail around 1938, Hemen returned to Calcutta and was shocked to find his mother sick and working in Hemen’s uncle’s house. The state of affairs mandated that Hemen take up a job to support his mother and younger siblings, and a meeting with Subhas Bose resulted in Hemen getting employed as his secretary. Subsequently, Bose wanted Hemen to represent India at the High Commission in London. Hemen might have considered it as a career option, but his mother was dead against her son going abroad. It was then that Hemen was able to convince Bose about the power of the medium of cinema as a propaganda tool. Bose introduced Hemen to B.N. Sircar of New Theatres, where Hemen began his life in films as the fifth assistant to Debaki Bose, working as a helper in the costume department.

Not to be bogged down, Hemen went on to make a film on the 1905 partition of Bengal, Bhuli Nai (censored in 1948, made a year or two before). The film was rejected by the board of censors in Bengal. A show meant for the press was organized in Bombay, and subsequently the film was passed by the Bombay censor board for viewership in Bombay. This was supplemented by a documented criticism of the Bengal censor board. With time, the film was cleared by the censors at Tripura, Bihar and Orissa. The chief minister of Orissa also inaugurated the film screening ceremony in Cuttack. The Orissa government also purchased a few prints of the film in 16mm format. In 1950, the film was screened as a special feature during the Republic Day celebration at Guwahati, Assam.

Hemen Gupta is on record that Bhuli Nai was turned down by the censors a record eight times. The main objection raised was an excess of violence. In retrospect, Hemen had simply recounted what he had experienced in jail. Maybe it was too brutal, too in-your-face and too real for the make-believe world of cinema. Notwithstanding the stand taken by the censors in Bengal, the film touched a chord with the masses, especially migrants from East Bengal.

For his next venture, ‘Biyalish’ (42) (1949), Hemen drew inspiration from the Quit India movement. Unlike his own revolutionary ways during his younger days, in 42, Hemen seems to espouse Gandhi’s peaceful demonstration of ‘Karenge ya marange’ values while being targeted by the sadistic Major Trivedi (Bikash Roy) and his men. Hemen recounted that Bikash Roy’s portrayal of Major Trivedi was so powerful and realistic that after the release of the film, Bikash was hesitant to step out on to the streets, fearing attacks from the public.

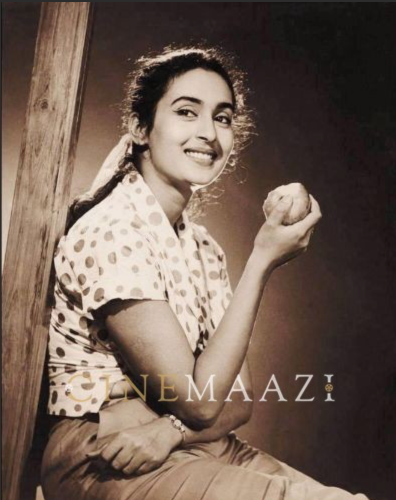

Sital Batyabal, christened Pradeep Kumar by Debaki Bose (uncorroborated), had to wait for over three years for his most acclaimed Bengali film to release. Pradeep Kumar had worked in a college play with Ratna Gupta, and it is through her that Hemen came to know about the once trainee at a leading hotel in Calcutta (probably Great Eastern Hotel) who also dabbled in plays. He became a trusted member of Hemen’s team.

Bombay

At the behest of Sasadhar Mukerji, who was rebuilding Filmistan after Ashok Kumar had returned to Bombay Talkies, Hemen travelled to Bombay in 1950. He was promised a fat pay cheque too. He also bought assurance from Mukerji about select team members accompanying him. Hence, we had a tall and personable gent with a baritone debuting as a composer in Hindi films with Anand Math (1952), which marked Hemen’s debut in Bombay. Hemanta Mukherjee was billed as ‘Hement’ Kumar Mukherjee in the film. He would later be rechristened Hemant Kumar. Hemant had to rush to Bombay, leaving the background score of Jighansha (1951) incomplete. Ajoy Kar, the director and cinematographer of Jighansha, was also Hemen’s recruit who subsequently came to Bombay. Pradeep Kumar also came to stay. Even in his first Hindi film, he was billed above Bharat Bhushan.

Hemen and Ratna Gupta were now gradually settling down in Bombay. They had put up as a tenant on the ground floor at Roop Kala on 16th Road, Khar, at the intersection of Khar-Pali Road. The landlady, who used to stay on the first floor, was keen on a career in cinema. She and her daughter both acted in bit roles in Anand Math. The toddler later became an eminent child star. Daisy Irani.

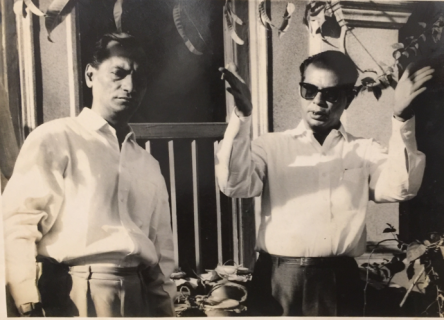

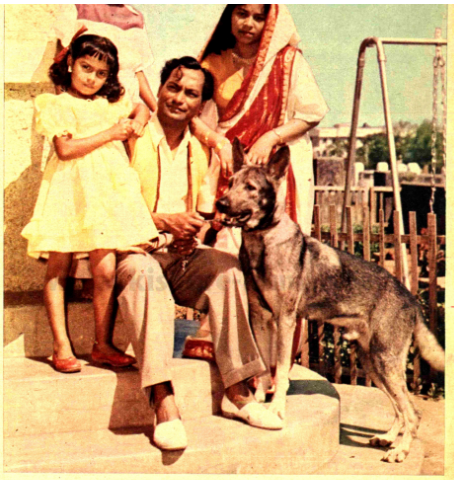

By the time Hemen quit Filmistan to venture out on his own, his son Jayanta was seven. Daughter Jayshree aka Bula was three. The family had their first pet too, Sardar, an Alsatian. The couple had unfortunately lost their first child, Rubu, to a freak accident which happened on a train journey when the windowpane fell down on her hand.

Actress Sabita Chatterjee goes back in time discussing Hemen Gupta and his family. ‘I was new to Bombay and their neighbour from the late-1950s. Their house was not very big, but the drawing-cum-party room was. Hemen-babu was tall, good looking and kind. He loved to give parties. I found a lot of love in their household. They used to say that they had a daughter like me who passed away when she was an infant.’

Even in the event of a tragedy of indefinable proportions, involving the death of a child, Hemen was not crestfallen. He had in him to fight. An anecdote by his son Jayanta reinforces this view. ‘An interesting incident took place in the mid-1950s, when my father’s experiences as a freedom fighter saved the day for us. We were travelling from Bombay to Calcutta in a first-class compartment (a separate coupe, not internally connected to the other compartments in the train). When the train was somewhere near the West Bengal border, two armed men entered the compartment, with an intent to rob. My father asked us to remain calm. He managed to get into a conversation with the two dacoits, sharing his personal experiences in the murder of a British officer, the robbery of a train and his jail term. All this fascinated the dacoits, who listened to him with rapt attention. At length, the train slowed down, approaching a station. The two men apparently decided that they would not rob us and jumped off the train, leaving us unharmed.’

In Bombay, Hemen turned an independent producer (he was the producer of Anand Math too, but for all practical purposes, the control was with Filmistan) with Kashti (aka Ferry). In complete contrast to his earlier films, this was a love story. And a film for children as well, the main characters played by Jayanta Mukherjee (Hemant Kumar’s son), Jayshree (Hemen’s daughter), and her pet Sardar, who was named Lassie in the film. The pair of Pradeep Kumar and Geeta Bali was carried over from Anand Math, with Dev Anand replacing Pradeep Kumar at the last moment, probably because Kumar was busy with Filmistan’s Anarkali (1953) and Nagin (1954).

In the 1950s through to the 1960s, the term niche-but-successful-film-maker did not exist in Bombay. As a result, survival was a major challenge for film-makers without commercial clout. Hemen never was a big film-maker. He did not have the patronage of any particular film fraternity either. The period after Kashti was not particularly pleasant. He struggled, and badly too. Two of his productions – Raaj Kamal (starring Madhubala and Pradeep Kumar, its muhurat was performed by the famous Italian director, Roberto Rossellini) and Insaaf Kahan Hai – remained incomplete. Some of his concepts did not materialize, like the one he had thought about the burning of slums in Kanpur. Had it not been for Bimal Roy offering him Kabuliwala to be made on the occasion of Tagore’s centenary, his Bombay chapter could be tagged as inconsequential, especially after 1954. The only film of some repute he manged in the six years in between was Taksaal, where the focus was on the conflict a lawyer is subjected to in his life. Balraj Sahni, the protagonist of Taksaal, was the protagonist in Kabuliwala as well.

This was a film where the government could have pumped in money, as not only did Hemen know Netaji well, he had also worked under him and had entered films with his blessings. The Film Finance Corporation’s policy of financing films through loans for small budget, offbeat cinema came into force only in 1968. Released on 22 April 1966, in Bombay, Baroda, Jaipur, Jodhpur and Ajmer, and earlier in states where good reception was guaranteed, West Bengal and Punjab, Netaji was a washout in every respect.

Plagued by lack of artistic freedom and constrained by the demands of the financiers, Hemen decided that it was time to go back to his roots and make a film in Bengali with actors from both Bombay and Calcutta. Hemen went to Calcutta for the muhurat where luminaries including Satyajit Ray blessed the film. Prithviraj Kapoor, the lead in Hemen’s first Hindi film, was back. Madhabi Mukherjee, a most sought-after actress after Ray’s Charulata (1964), was to play the title role. Anamika, as the film was named, had Anil Chatterjee as the hero. Interestingly, Dharmendra and Shashikala were also there in guest roles. The story, partly on the lines of Stella Dallas (1925), was about a lady who, after disfiguring her face in an accident, comes back to the family as a governess to be with her child. A few songs had been recorded too.

Talking about songs, Hemen had an excellent ear for music. He was trained in music by a state singer of Kashmir, followed by another spell of training under his party leader Anil Rai during his days of incarceration. Daughter Jayshree, a well-known singer during her college days, however does not recall her father singing, though she agrees that he had a good musical sense and would hum quite often. (The Gupta family is very Von-Trappish in that sense; all the members are musical. Ratna Gupta was an accomplished and recorded singer, having trained in Calcutta in multiple genres, especially Rabindrasangeet. She was also Sachin Dev Burman’s student, albeit for a very short time. Her songs in Bhuli Nai, 42 and Kashti were well received during their time. Jayanta too is musical; he plays multiple instruments including the tabla and the chromatic harmonica, and has also sung for Salil Chowdhury for his album recorded in the US. Jaijeet, a fanatic when it comes to Kishore Kumar, composed and produced a music album of love songs, sung by Alka Yagnik and Kumar Sanu in the 1990s where the orchestra was arranged by Bablu Chakraborty.)

Hemen could never finish the film. While leaving for work on a sunny day in the last week of June 1967, he had a splitting headache and had to be transferred immediately to Nanavati Hospital, where the doctors diagnosed it as a brain stroke. His son Jayanta, then a student of IIT, Delhi, was in Bombay for his summer holidays. He recalls that the entire film industry came down, especially the neighbours, which included people like Rahul Dev Burman. But the person who refused to go home was Basu Bhattacharya, who extended every kind of help possible.

Hemen passed away on 1 July, leaving a family, and lots of incomplete dreams. For a person who ridiculed death – almost been to the gallows twice – his sudden demise was shocking not only for the family, but also for anyone who knew him well. Most of them vouch for Hemen’s stout heart. Anuradha Gupta recalls that Misri-Kaku had no qualms in letting his toddler Jayanta – who played Pradeep Kumar’s and Manju Dey’s son in the film – die in 42. When questioned by the family, Hemen’s response was a belly-shaking laughter. ‘Come on, it is only a film. Let’s move on in life.’

Hemen’s life made for fascinating paradoxes. Hemen was a believer in charity. He used to donate liberally to people around him since the time he was a revolutionary. He was also deeply grounded. Jayshree reminiscences that the entire family would eat on the floor sitting on hand-woven mats on Sundays. Food was served on banana leaves from the garden. While the children loved it, the exercise also inculcated in them the values of humility. At the same time, Hemen was almost Page 3 material. The Gupta household was suave, urbane and known for big filmi parties which carried on till early morning during weekends.

Experience had perhaps moulded him to demarcate between dogma and practicability. Reason why he might have accepted films like Meenar. At times he was forced to make major changes to the storyline, at the behest of his financiers and distributors. For instance, the ending of the film Taksaal was drastically changed to the utter dismay of Hemen. He accepted the diktat against his principles. He needed to survive the battle to fight the war.

Hemen treated people with utmost dignity. The family often went to dine at Nanking in Colaba, south Bombay, where Hemen would chat with the chef, the maître d'hôtel and other Chinese waiters, addressing them by their names. And incidentally, he spoke to them in Bengali as most of them were from Calcutta and knew the language.

Epilogue

Life after Hemen was not easy for the Gupta family. Ratna Gupta had to struggle for a freedom fighter’s pension, something she could manage around 1992–93 after repeated visits to the pension office at Khan Market, New Delhi, and a meeting with the then MP Rajesh Khanna. After graduating from IIT Delhi in chemical engineering, Jayanta Gupta worked in countries like Indonesia and the USA (where he settled down), and currently resides at Toronto. Younger son Jaijeet stayed back in Bombay and manages his own business house. Jayshree, after a short stint as a singer and an actress (while pursuing her graduation in economics at St Xavier’s College, Bombay), married in 1974 and later settled down in the NJ area in the US. We all know her as the bubbly leading lady of the early 1970s, Archana, of Buddha Mil Gaya (1971) fame. But that’s a story for another day.

(The author thanks the following people he had interviewed/contacted for the story/or pictures): Jayshree Motwane (aka Archana Gupta), daughter; Anuradha Gupta, niece; Ira Sensharma, wife of maternal nephew; Sabita Chatterjee (aka Shobha Sharma), actress and family friend; Lopamudra Dasgupta, sister-in-law of Jayanta Gupta; Nandan Dasgupta, brother-in-law of Jayanta Gupta; Monojit Lahiri, writer and advertising veteran; Dolon Sen, relative; Rinki Roy Bhattacharya, family friend; Kaustubh C. Pingle; Sudarshan Talwar; Abir Bhattacharya, film researcher; Madhabi Mukherjee, actor; Raj Kaushal Chatterjee, film-maker; Joy Bhattacharjya, sports journalist and media veteran; S.M.M Ausuja, archivist; Devdan Mitra, editor, ‘Sports and The Woods’, The Telegraph; Late Bhaskar Rao, Sreeya Ghosh, granddaughter of Netaji’s brother Sarat Bose; Gourab Roy Chowdhury, Dubai-based film historian; Arnab Banerjee, film aficionado; Archisman Mozumder, Hindustani classical expert; and especially Jayanta Gupta, son, without whom this story could not have been written.)

References

Interviews of Hemen Gupta in Sports and Pastime and Filmfare.

Annexure: Family Tree

Tags

About the Author

Anirudha Bhattacharjee is an alumnus of IIT Kharagpur who works as an SAP consultant. He divides his time between work, family, singing, solving puzzles, quizzing, and watching football or films of Wilder, Hitchcock, Satyajit Ray and anything that has the semblance of a biopic/comedy/noir/alternative history. A writer by accident, his area of interest is mainly Hindi and Bengali cinema between 1950 and 1985. He is the co-author of the National award-winning book R.D. Burman: The Man, The Music, the MAMI winner Gaata Rahe Mera Dil and the critically acclaimed S.D. Burman: The Prince-Musician. Anirudha stays in Bangalore with his wife Sudipta and sons Aritra and Shaunak, all of whom share his passion for cinema.

.jpg)