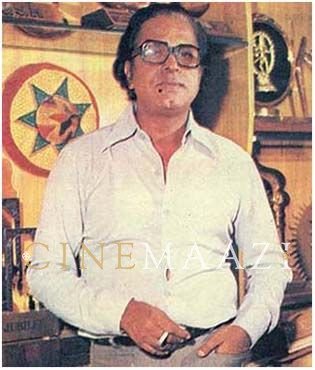

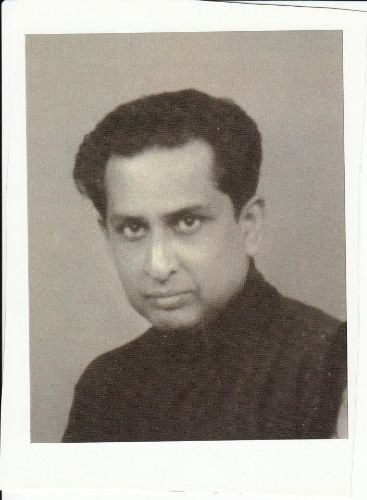

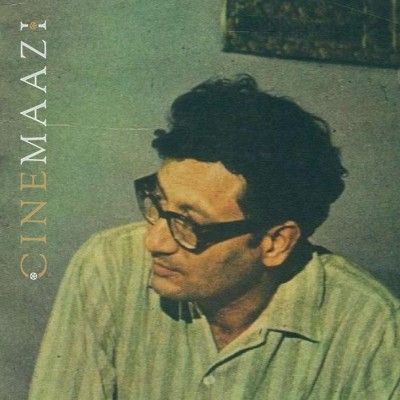

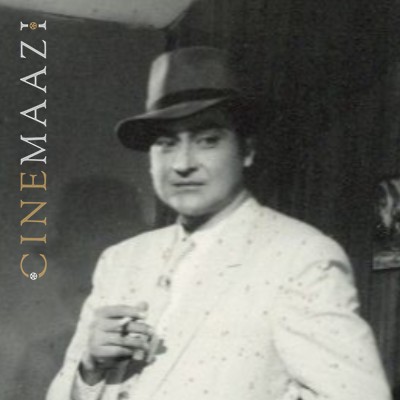

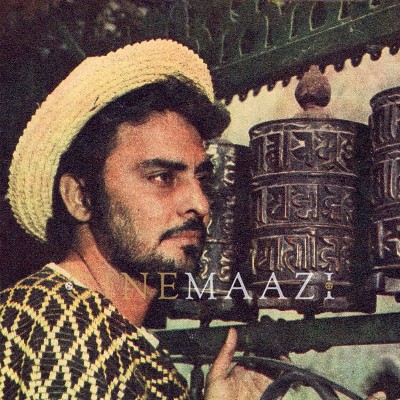

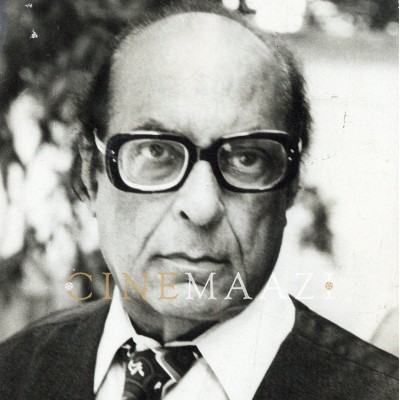

Basu Chakraborty

Subscribe to read full article

This section is for paid subscribers only. Our subscription is only $37/- for one full year.

You get unlimited access to all paid section and features on the website with this subscription.

Not ready for a full subscription?

You can access this article for $2 , and have it saved to your account for one year.

- Real Name: Basudeb Chakraborty

- Born: 23/01/1928 (Calcutta)

- Died: 27/07/2001 (Bombay)

- Primary Cinema: Hindi

- Parents: Basanta Kumar Chakraborty, Krishna Mohini Devi

- Spouse: Pootul Bhattacharjee

- Children: Swapna, Sanjay

Whether blowing into bottles during the recording of songs like Mehbooba Mehbooba (Sholay, 1975), arranging purely string-based obligatos, or composing the harmonica refrain and the introductory theme to Gabbar Singh, Basu Chakraborty remains unforgettable.

The tenth and last child in a family of five brothers and five sisters, Basudeb Chakraborty was born in Calcutta on 23rd January 1928 to Basanta Kumar Chakraborty and Krishna Mohini Devi. The Chakrabortys were a joint family, and the household was active on multiple fronts. While Basu did his matriculation in 1944 from Town School, it was a career in music he aspired to, having been introduced to music early in life via his youngest uncle (Chhoto Kaka) Ananta Kumar Chakraborty, who frequented musical soirees and plays in the neighbourhood.

Basu’s real inspirational guru was his elder brother, Kamala Kinkar Chakraborty. An avowed follower of Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose, Basu was a member of the Forward Bloc as well. Kamala Kinkar had started a music school near his house, which many musicians used to frequent. However, Basu Chakraborty’s formal training had already started under Basanta Gupta. Gupta was a well-known fiddler and also an assistant to K.C. Dey, adept at both the Hindustani and Western styles. He taught Basu the violin, the viola and the cello. This mix of Indian classical and sheet music basics would add immense value to Basu’s career.

It was in his teens that Basu started earning. Bandhab Samaj Club used to hold jatras (Bengali folk-form theatre). One famous jatra was Nadia Binod in which renowned actor Chhabi Biswas was cast as Nimai, the lead character. Basu’s professional life as a string-section musician started there.

Till the late 1950s, film producers in Calcutta would enter into a contract with professional orchestras for the background scores. Basu joined Surashree Orchestra. Basu was working for composers like R.C. Boral, Pankaj Mullick and Anupam Ghatak as well, alongside working on the most famous Bengali radio play ever -Mahisasuramardini. Basu’s association with the play started in 1948. It used to be played live then, till a version was recorded for the radio a few years later.

Basu’s work as a cellist had impressed Mullick deeply, and he would be summoned quite often for arrangement and handling the string section, apart from playing the cello. Zalzala (1952) was a Bombay production which Mullick was working on at that time. He handled the music from Calcutta. Paul Zils, the director of Zalzala (1952), had started another film, Situm, where Mullick was again the music director.

Post Partition, Calcutta was fast losing its importance as a centre of cinema. While the focus had shifted to Bombay, Madras had emerged as the more professional of the two centres. In 1953, Basu tried his luck at Madras, only to return in a year. Back in Calcutta, he had started taking lessons from a Russian cellist who was staying at Wellesley Street. There have been unconfirmed conjecture that the cellist could be Sviatoslav Knushevitsky, who had come with Khrushchev in 1955 as part of an exchange programme. During this comparatively lean period, he found work with a new filmmaker, Satyajit Ray. Basu worked in four films of Ray in which Pandit Ravi Shankar was the composer. He was also formally credited in the titles of Aparajito (1956).

It was during a concert that Salil Chowdhury and Naushad –both at loggerheads where musical ideas were concerned – saw Basu performing. Both agreed that these artistes mandated a greater stage. He soon made the move to Bombay, staying as a guest at Salil Chowdhury’s house. Post marriage to Pootul Bhattacharjee in Calcutta, he moved to the mezzanine floor of a tenement in an unposh area of Bombay.

In Bombay, group dynamics, politics, nepotism, etc., played a major role, mostly because the music fraternity was fragmented, based on caste, religion and, particularly language. Bengali musicians especially were not welcome. However, Basu did find work. The week after Basu’s daughter Swapna was born, he received information through Pancham (R.D. Burman) that S.D. Burman wanted him as a sitting member. It was November 1958. The background score of Bimal Roy’s Sujata (1959) had to be completed. Thus, began his 25-year association with the Burmans. By the time he first worked as an arranger for Pancham in Bhoot Bangla (1965), his son Sanjay had been born, in July 1963. Basu was the second ‘Navaratna’ (the first was Maruti Rao Keer) and an indispensable member of Pancham’s sittings and recordings.

A gifted conceptualizer, as seen in Guide(1965), Basu went against what S.D. Burman wanted and used long bars of music as fillers. The fillers are intricately woven and lead on to the interludes. The results were widely appreciated. At a time when most cellists were from Goa, Basu was probably the first Bengali from Calcutta who made a living as a cellist-cum-arranger. An interesting example could be the song Ek din aurgaya (Manna Dey in Door ka Rahi, 1971), where the cello serves as the base for most of the fillers, which were both arranged and played by Basu too. Composer Kishore Kumar became his fan for life, pestering him to accompany him on his trips abroad and also be a part of his compositions. Basu gradually became the first choice for many others as well. During the making of Shakti Samanta’s Amanush (bilingual, 1974–75), Basu merged music director Shyamal Mitra’s Bengal-flavoured tunes with the instrumentation in a consistent and organic manner.

He also carried the entire task of writing notations for the melody and the strings on his shoulders. He was not only musically learned, but also very disciplined. His reaction time was short too. He could assimilate the requirement and transfer the same on paper in a matter of hours. A hard taskmaster, time-wasting was a phrase absent in his dictionary, one of the main reasons why Pancham’s recordings were cost-effective and hardly stretched beyond the stipulated time frame.

Basu also did some work as a composer with his friend Manohari. He composed for films with stringent budgets, and with actors who were not exactly saleable. Given the limitations of time, cost and resources, the results were fabulous. The duo started with an untitled film Jalal Agha was making sometime after his debut in Bambai Raat Ki Bahon Mein (1968). Basu had composed two songs to lyrics by Majrooh -a cabaret for Asha, Dil lagi nahin dil ka lagana, and a romantic solo for Lata, Bheegi bheegi palken kyon bhare bhare nain. The next film was Yasmeen (1973). Both films never released. Two songs from the latter went into Devan Varma’s Chatpatee (1983). These have great recall value today, especially among aficionados.

The film that finally got the Basu–Manohari team well-deserved recognition was Sabse Bada Rupaiya (1976). There was very little to demarcate between a score by Pancham and the songs in this film. The genres close to Pancham’s heart – blues, bossa nova, big band sound– all found a place in this album. The recording happened at Film Center in Tardeo, which was a second home to the quartet of Pancham, Basu, Manohari and Maruti Rao. The team later did hugely popular Bengali Puja albums for Mohammed Rafi and Kishore Kumar.

An avid chess player, Basu was often found engaged in the game with Pancham or Hrishikesh Mukherjee. He also loved cards, and his family in Calcutta remember him as a good player of both the versions of the bridge – auction and contract. To the musicians, however, Basu had a military-like demeanour. He tried to preserve the façade of a perennially strict person. It is said that Basu never recovered from the sudden death of his nephew Deba Prasad Chakraborty, a fiddler in Pancham’s team and Basu’s constant shadow, in 1981. In February 1982, Basu had a heart attack after which the doctor advised him not to conduct orchestras during recordings. He had to cut down on work during this phase. Satte Pe Satta (1982) was the last film where he wrote notations and obligatos for Pancham.

Basu Chakraborty passed away on the night of his son’s birthday in 2001, on 27th July.

References

Information courtesy: Anirudha Bhattacharjee

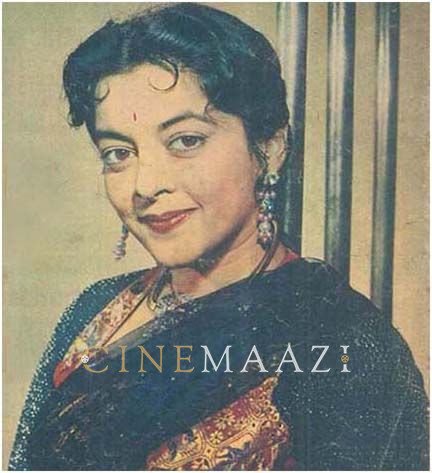

Image Courtesy: Mita Swapna Chakraborty

.jpg)