This section is for paid subscribers only. Our subscription is only $3700/- for one full year.

You get unlimited access to all paid section and features on the website with this subscription.

Subscribe to read full article

This section is for paid subscribers only. Our subscription is only $37/- for one full year.

You get unlimited access to all paid section and features on the website with this subscription.

Not ready for a full subscription?

You can access this article for $2, and have it saved to your account for one year.

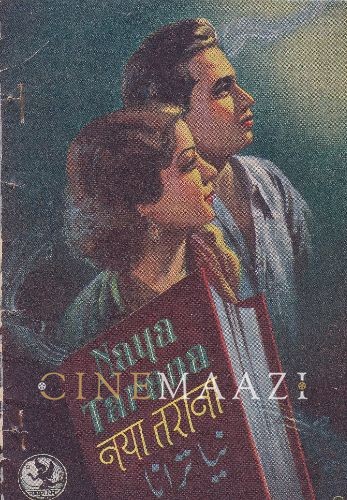

- Release Date1943

- GenreSocial

- FormatB-W

- LanguageHindi

According to the eternal laws of action and re-action, thesis and anti-thesis, oppression .breeds mass discontent and exploitation is the mother of revolution. And even as sometimes a poison may serve as an anti-dote, so does history use the children of the exploiting classes to bring about the end of exploitation.

ANAND'S father was a zamindar, a cruel, hard-hearted oppressor. But Anand had been to college and studied economics and political science, read about the French and Russian Revolutions, and how and why they were caused. To him, his father's ways were not only bad in themselves, but they represented and symbolized a vicious and rotten system. Anand's sympathies were entirely with the peasants and, being a poet, his voice of protest against the inequities of the zamindari system burst out in revolutionary song.

A clash between two strong minds was inevitable, Anand left his comfortable home and went to the city to earn a living by the sweat of his brow.

But the economic system that oppresses the peasants, in the village is present in another form in the city also. Anand found himself, a misfit, in every job he secures. Soon he was reduced to unemployment. He was living with his old college friend, Anwar, who was himself far from being rich except in his generous heart. Anand had, meanwhile, published his collection of poems, appropriately entitled, NAYA TARANA, for, each his poems was, indeed, a new anthem of freedom, breathing hope for the downtrodden masses, and hurling defiance at the citadels of raction and oppression. But it seemed that a public, doped with spicy, sexy novels, had no taste for revolutionary poetry. The copies lay unsold in the bookseller's shop, for a week, two weeks, one month and the barometer of Anand's hopes dropped lower and lower—till one day it leaped up again when he learned that as many as 50 copies had been sold. Who could have bought all these copies?

As Anand pondered this question, fifty girls were lustily singing the NAYA TARANA song, the chorus being led by KALAVATI, the prettiest, smartest, and most intelligent girl in the college. It was she who had bought the first copy of the book and then persuaded all her classmates to do likewise. She had fallen in love with the stirring poetry—and with the unknown poet. The lofty idealism and impatient purpose of Anand's songs of freedom had found an echo in her heart and given her vague idealism a purpose and a direction—a direction that was too dangerous for the daughter of a millionaire. Kalavati was turned out of college and.earned the displeasure of her father, but she did not rest content until she had found the poet Anand and made him known to the world. The two met each other in amusing circumstances, several times meeting and yet not meeting, but once they knew each other their common idealism soon flowered into the deepest emotion of love.

To one man this pure love was distasteful in the extreme. He was MANI RAM, young and unscrupulous money-grabber, who had pretensions of being something of a lady-killer. When Kala rejected his proposal, he made up his mind to avenge this insult and bided his time.

Anand's father, mellowed and softened by the son's renunciation in the cause of idealism, died with the name of Anand on his lips. Anand went home to console his mother and got caught in the tentacles of a famine that had the whole countryside in its vicious grip. Kala, misunderstanding his long absence, went to the village to remonstrate but arrived to admire the self-sacrificing way in which Anand was serving the peasants. "Repaying the debt I owe them in lieu of my ancestors' oppression." Both decided to collect money by means of a charity show for famine relief but, thanks to the machinations of the wily Maniram, the scheme flopped. The peasants were left to starve. Where was the grain?

The grain was locked up in the underground cellar of Maniram's house. When the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbour, Kala's father Seth Lakhmichand lost all his wealth which—at the suggestion of the double-dealing Maniram—had been invested in trade with Japan. Maniram, on the other hand, had speculated shrewdly and made millions. He decided to make more millions out of the thousands of tons of grain he had secretly hoarded.

These, then, are the ingredients of a drama of immense topical significance; Starving peasants; a grain hoarder; two idealists, Anand and Kala, in love with each other but even more in love- with the idea of social justice, personal sacrifices, misunderstandings, emotional outbursts—they all form a part of the dramatic pattern. But the happy denouement is brought about only when the people move to redeem the honour of their leader and to expose the profiteers. The final triumph of Anand and Kalavati is the triumph of the people.

[from the official press booklet]

Cast

-

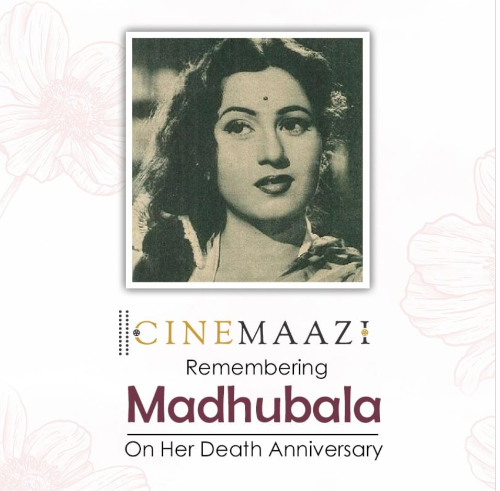

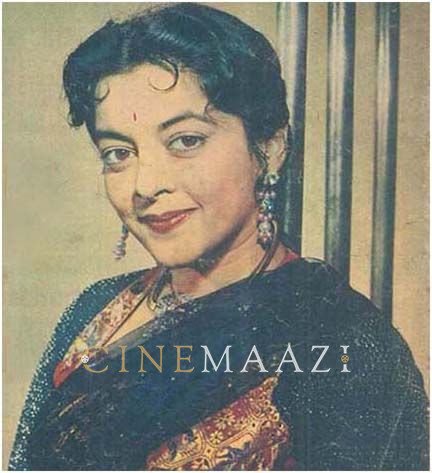

Snehprabha Pradhan

Kalavati

Crew

-

BannerNavyug Chitrapat Ltd, Poona

-

Director

-

Music Director

-

Director

-

Lyricist

-

Screenplay

-

Cinematography

-

Editing

-

Sound Recording/ Audiography

-

Art Director/Production Design

-

Costumes

-

Make-up

-

Story & Dialogues

.jpg)