A Touch of Greatness: My Encounters with Manik-da

Subscribe to read full article

This section is for paid subscribers only. Our subscription is only $37/- for one full year.

You get unlimited access to all paid section and features on the website with this subscription.

Not ready for a full subscription?

You can access this article for $2, and have it saved to your account for one year.

On Satyajit Ray’s birth centenary, Rinki Roy pays a tribute to her distinguished mentor.

Unknown to me, Mother had invited a celebrated guest that particular night. And she extended her gracious invitation to us, me and husband Basu, for the special occasion. Dining with her was always a welcome affair. Her lavish hospitality and the gourmet repast each invite promised were well known. So, I rarely passed up a meal with mother.

That night, however, she added something that struck me as odd.

‘Come by 8.30,’ she said before hanging up.

By the time we reached Godiwala Bungalow, mother’s place, it was well past nine. Her guests had arrived and were comfortably seated in the elegant Jacobian sofa set bought at a local auction.

From the corner of my eye, I saw that famous leonine head turn 360 degrees and almost immediately his deep voice echoed in the vast Godiwala Bungalow hall: ‘Rinki? The one who writes?’ he said nonchalantly.

Without getting up from his seat, mother’s celebrated guest made this extraordinary pronouncement about me. The impact of which almost knocked me down. Unbelievable! The world-renowned, busy director Satyajit Ray had noticed my utterly modest writings! I don’t remember if I blushed but I was tongue tied with pride and self-worth all evening. Till date, his words gleam like gems secretly shining within.

After that, there was no looking back. Literally, none whatsoever. Emboldened by his generous recognition, I began to interact with Manik-da on one pretext or another mainly through letters. My letters were informal observations about his films, or film related. They amounted to little more than chitchatting. But Manik-da never failed to answer back. From writing inconsequential letters, I graduated to making personal phone calls. Manik-da himself received his telephone calls … amazing that a man of his stature did not bother to engage a secretary. Every time I visited Calcutta, a visit to his Bishop Lefroy flat became the trip’s highpoint. Manik-da seemed ever ready for an informal adda along with yummy homemade savories that his charming wife, Bijoya mashi, served with tea.

‘How did you two come? Taxi? You better head home. Mrs Gandhi has been shot. There will be a vicious backlash.’

BBC radio had confirmed Mrs Gandhi’s death while the Indian news channels dragged their feet fearing fierce backlash. We left the lively adda reluctantly to return home. For the first time I realized that most Calcutta taxi drivers are Sikhs. Including the one we engaged. However, we reached home safely. By late afternoon on 31 October, the entire Bhawanipur area with its imposing gurudwara, a Sikh-dominated Calcutta neighbourhood, was ablaze. By evening Calcutta streets were deserted. The traffic down to zero. The October trip turned out to be a tragic one.

Not only did I visit Manik-da during my Calcutta trips, if he happened to be in Bombay for dubbing, or recording with Mangesh Desai, I would grab time to meet him at the Shalimar hotel which apparently was his favourite place here.

‘So sorry, Rinki,’ he answered in his rich baritone voice. ‘I am busy shooting every day for my new film.’ Perhaps he guessed my disappointment. As an afterthought, he added: ‘But why don’t you come to the film set instead? In fact, come this afternoon. I am shooting with Richard. You would like that.’

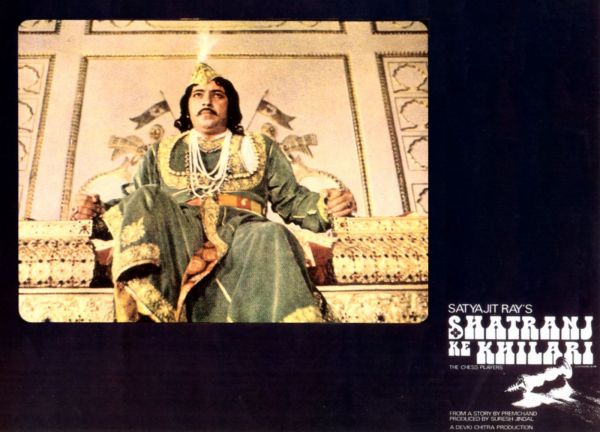

Needless to say, I was overjoyed at such a rare opportunity to watch Manik-da in action. I hastened late noon to the Technicians Studio in Tollygunje. One of the first persons I saw hanging outside the floor was the young, unknown Victor Banerjee Manik-da introduced with two close-ups in Shatranj Ke Khilari.

Inside the floor was the elaborate Oudh palace set meticulously created by art director Bansi Chandragupta. I was thrilled to see Sir Richard Attenborough appear in the role of General Outram with actress Veena (Wajid Ali Shah’s screen mother). The short scene that day was of the two trying to negotiate Wajid Ali’s abdication. I remember Tom Alter loitering somewhere in the background.

Shatranj Ke Khilari, regrettably, encountered extremely hostile opposition from the Bombay film industry. For example, the date for the film’s all-India release was announced. I remember seeing a huge billboard at Worli looming opposite Haji Ali. To our utter dismay the banner was hastily pulled down and the film’s release indefinitely postponed. Industry rumours that the Bombay film industry did not welcome his entry was an open secret.

Being an ardent devotee of Manik-da, I was boiling at the shabby manner in which the Bombay film industry treated him. As if he was about to upstage them. Wanting to know the inside picture, I called up producer Suresh Jindal. The untold story that emerged after our long-distance conversation was shamefully humiliating. I felt obliged to write an exposé. The Sunday magazine, edited those days by M.J. Akbar, carried it as a lead story. Once the Shatranj story was out, I began to be targeted in the print media as a self-styled Ray crusader!

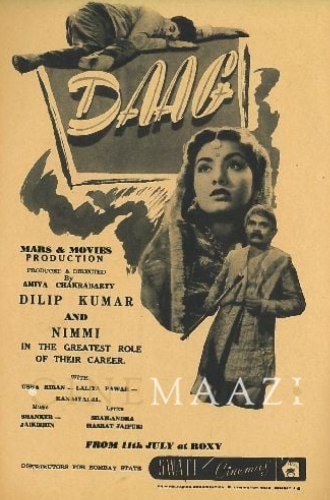

Interestingly, the dinner I mentioned earlier was when my mother hoped to discuss him directing a film for the Bimal Roy Production. However, Manik-da politely declined, admitting: ‘I am not comfortable with Hindi as you know.’

Ritwick Ghatak had proclaimed that Bimal Roy had pulled ‘Bengali cinema out of the abyss’. He, Mrinal Sen, Tapan Sinha virtually revered my father post Udayer Pathe. Manik-da, who was from the same generation, did not reveal his admiration. It was unexpectedly confirmed when I came across a rare nugget worth sharing. In a magazine interview by Jyotirmay Datta, Manik-da casually mentioned: ‘After Udayer Pathe Bimal Roy announced making Subodh Ghosh’s Fossil (Anjangad). I read the story, wrote the screenplay and went to meet Bimal Roy. He was apparently busy. I went back again. Though he recognized me as the cover illustrator of the Signet press, I returned disappointed.’

Although I enjoyed Manik-da’s affection, or perhaps because of it, I did not want to risk endangering our cherished bond. For several years therefore I did not share my much debated, indeed, the explosive 1984 Manushi interview. However, during one Calcutta visit, I left a copy of Madhu Kishwar’s marathon interview in which I laid bare the reasons for stepping out of my marriage. I even heard reports that my interview had raised uneasy question in Parliament on widespread spousal abuse. Though I left the copy of Manushi in a state of uncertainty, I was racked by pervasive anxiety about Manik-da’s reaction.

Manik-da’s letter remains one of my few prized possessions. It is a living testament of his unfailing compassion, his understanding of a universally trivialized crime behind closed doors that has justly earned the term domestic terrorism.

I remain in Manik-da’s debt for endorsing the spirit that compelled me to publicly speak against marital abuse. His support was conveyed privately, in a discreet style. Yet, it healed my broken spirit and restored my self-esteem that was being questioned daily by others who conspired to stay silent.

Tags

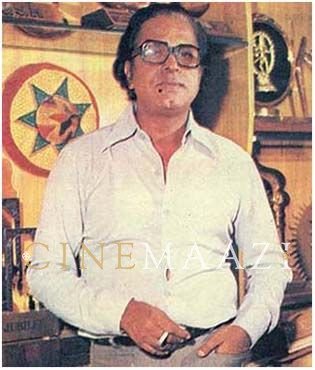

About the Author

Ms Rinki Roy Bhattacharya is a published author of Penguin/Random house, HarperCollins, and SAGE India, besides being a veteran journalist and documentary film maker. She has been a freelance journalist for reputed publications like Times of India and Indian Express. She has been the recipient of several prestigious scholarships including research fellowships & honorary doctorates. She has been invited on prestigious International and domestic Jurylike the Mumbai International Film Festival and Amsterdam Documentary Festival.. An acknowledged specialist on women and film studies, she is frequently invited to take master classes at reputed educational Institutions like Berkley, SOAS,TISS, NFAI, SNDT ,Sophia college amongst other places. She has been the Vice Chairperson of the Children's Film Society of India. She has been the recipient of multiple honours from the School of Oriental and African Studies in the U.K., TISS, Rotary Club and the Bangladesh government. She has co-directed the doucmentary Char Diwari and the short film Janani. She has edited multiple publications like Behind Closed Doors/Domestic Violence in India, Janani: Mothers, Daughters, Motherhood and Bimal Roy: The Man Who Spoke in Pictures and authored Bimal Roy, A Man of Silence, Bimal Roy's Madhumati: Tales From Behind The Scenes and Bengal Spices.

.jpg)