This section is for paid subscribers only. Our subscription is only $3700/- for one full year.

You get unlimited access to all paid section and features on the website with this subscription.

Subscribe to read full article

This section is for paid subscribers only. Our subscription is only $37/- for one full year.

You get unlimited access to all paid section and features on the website with this subscription.

Not ready for a full subscription?

You can access this article for $2, and have it saved to your account for one year.

- LanguageHindi

Now-a-days I do not get the leisure to sit by and read books; the energy to do so is also lacking. My mind likes to fly along trackless ways, my body is work-shy.

Still I have read your book, “Mahaprasthaner Pathey”, not to oblige you, but having been impelled by sheer necessity to go through it though my own work has suffered thereby.

Your vision, your mind and language in this book of yours are all on the move; they take the mind of the reader out onto the road. Your writing runs, not along the scriptural nor the geographical channel, but along the way which men have trod on.

The endeavours of adventurous people to undertake perilous journeys are flowing in a ceaseless stream down the centuries. This pilgrimage is a symbol of that endeavour in which your too were drawn for a time. In our homes men are but the continuous succession of previous generations: as they lie scattered, the bond that ties them eludes us. But in that narrow mountain path, the strength of the eternal procession of men drawn together to achieve a limited end is clearly discernable. In the proximity of their common purpose, they become closely related to the distant past and the on-coming ages. These people inhabit different provinces, belong to different homes; they are diverse-still they are one-and with them run joy and sorrow, hope and fear, the thrust and parry of life and death. The mind of man, the eternal traveller down the ages, has quickened your writing with the touch of its untiring curiosity-and its delight and interest drive the reader on.

In one, among the many incidents that your have described in your book of travel, your normal temperament has suffered an eclipse. On this pilgrimage in which you had the privilege to come in contact with a concourse of men and women-all sorts had gathered together-the educated and the unlettered, the pious as well as the dishonest. It is no mean thing to accept people so closely and in such a splendid fashion. Then why did you run away from a prostitute as soon as you learnt her to be one? why did you not watch her with unbiased curiosity combined with a larger detachment befitting a man of letters? How could you align yourself with those pious old dames who did not count you as a man for your slackness in devotion and conduct? there is a pity that is pure, a curiosity that stays immaculate everywhere. Why then this impurity in you-a man of letters as you are? From your description, I felt, that in this girl there was love-sprinkled humanity in a fuller measure than in most of those devout pilgrims. She had disrespect for none as she herself had tumbled down to the lowest rung of the social ladder. He that is above all bears the same characteristics. I suspect at times that you have not stated all the facts clearly Such a disclosure could have provided an explanation of your conduct.

However, this book of yours has earned the praise of the many; to that, I add my appreciation of it.

RABINDRA NATH TAGORE.

Your entire writing bears the sign that on your pilgrimage the “Tirthadevatas” could not enshroud your mind which you had kept open towards your fellow pilgrims.

–SARATCHANDRA CHATTERJEE.

(From the official press booklet)

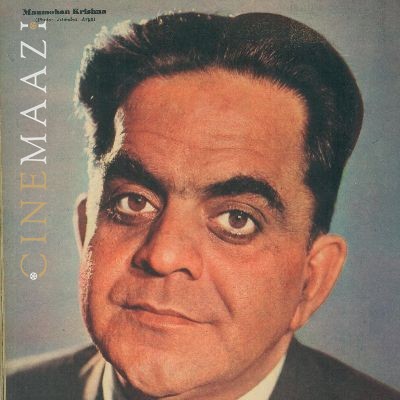

Cast

Crew

-

BannerNew Theatres, Calcutta

-

DirectorNA

-

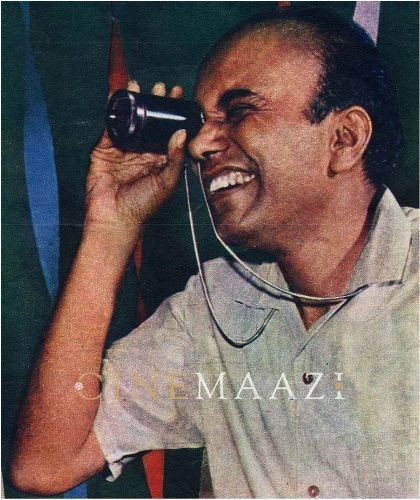

Music Director

-

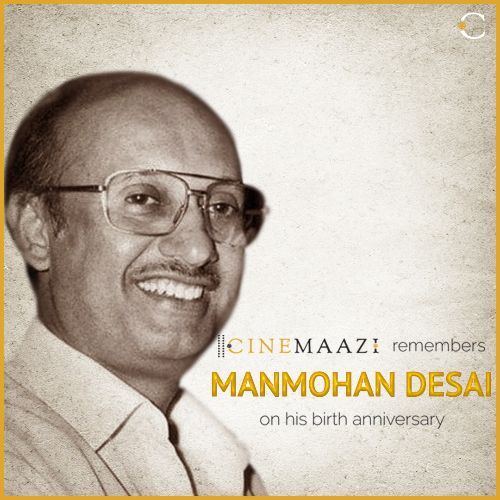

Director

.jpg)