We Still Hum the Song of the Little Road…

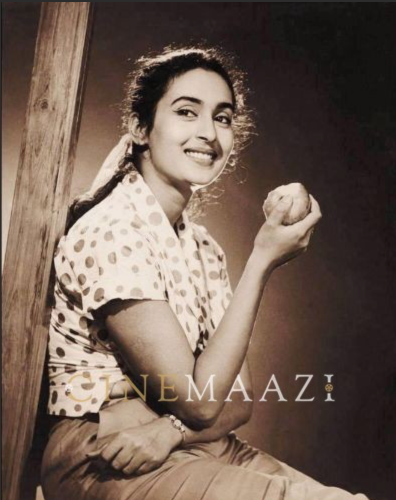

After Pather Panchali released, seventeen US magazines listed Uma Dasgupta, ‘the thirteen-year-old handsome Durga of the film’, as one of the teenagers of the year. The actor looks back at the making of what is now considered one of the greatest human documents in the history of cinema…

It was 25 or 26 August 1955. The release of Pather Panchali marked a watershed in the world of Indian cinema. Completely different from contemporary films, its language and style bowled audiences over. newspapers and journals, film academics and critics celebrated this change through various programmes and functions. Even fifty years on, it continues to overwhelm viewers. I keep getting the occasional invitation from some quarters, courtesy my role as Durga in the film – sometimes at functions like ‘Remembering Satyajit’ and sometimes in exhibitions on his films, or to deliver a talk on him or on opening a website in his name. All thanks to that one single film.

Let me first come to the selection of the novel. The pre-release advertisement for the film harped on ‘Unusual picturization of an Extraordinary Novel by Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay’. It was unusual and extraordinary, no doubt. In the original novel, Apu’s longing for an unknown and unseen faraway land is described in such poetic language that it touches the innermost chord of the reader’s mind.

‘…Not only to the ferry ghat – he knew this road went much farther; to the land of the Ramayana and the Mahabharata. … That road, the verdant green, the wonderful hill range under the blue canopy surrounded by clouds – these were not in any country described in the Ramayana. Nor were Valmiki and Bhavabhuti their creators. But, in the fertile imagination of a boy in a village alive with the sound of birds chirping at dusk, in some ancient time, they were real, absolutely genuine and well entrenched.’

Reminiscing over Satyajit Ray’s ‘Apu Trilogy’, I find that while doing the artwork for Aam Aantir Bhenpu – the abridged version of Pather Panchali published by Signet Press – Ray wanted to work on the scenario for the novel; later it developed into an intense desire to film it. Satyajit Ray captured the very same poetic mindset reflected in the novel through the childhood and adolescence of Apu and Durga, through the many trials and tribulations that a poor family in rural Bengal goes through.

The location was chosen with great care. The novel had as its background the village Gopalnagar where the author grew up and became a teacher. Initially, Satyajit Ray took some shots there – Apu and Durga running through the kaash flowers to see the train. Due to various problems, however, those 1952 shots could not be incorporated in the final film. Work on the film had to be stopped midway for dearth of money. Work resumed with new vigour in 1954 in the village Boral, not far from Kolkata. It is now a bustling township.

None of the actors in the film, barring Kanu Bandyopadhyay, was a professional. That is probably why the film’s surroundings and its characters come across as so fresh, so natural. Subir (Apu) was so young that he had to be literally cajoled into acting, with inducements and by explaining everything that he needed to do. Yet the innocence of his face, the way it conveys feelings and emotions, through frequent blinking of his eyes, created such an enthralling portrait, thanks to Satyajit Ray’s magic wand.

Thinking of those days makes me nostalgic. Take the scene of Indir Thakrun’s death. Durga and Indir Thakrun share a mutual bond that goes beyond the usual aunt-niece relationship. Both are victims of Sarbajaya’s sharp tongue and unwitting cruelty. Durga first experiences death through that of the most beloved person in her life. Just think of that scene: Apu and Durga playfully running along the jungle track, reciting nursery rhymes. Seeing her aunt sitting alone in the bamboo grove, Durga goes forward. With what precision Manik-da explained how pathetic this death was to Durga. How in a whispering tone Durga calls ‘Pishi, Pishhi, Pishi’, gets no response, shakes her a little and the aunt’s body tumbles. Manik-da instructed me on how to convey an expression of bewilderment at the shock mingled with helplessness. He was happy with my performance. But I just could not do the next scene – Durga silently weeping at Indir Thakrun’s verandah. But genius that he was, Manik-da managed to overcome this shortcoming on the part of the actor by capturing Durga’s tearful eyes in chiaroscuro, creating a mournful ambience…

Manik-da worked on my performance sequence by sequence, one at a time. Take, for example, the scene of the theft of Tuni’s garland of beads. A humiliated Sarbajaya is beating Durga mercilessly. Manik-da advised Karuna-di not to think of my getting injured but to go on beating me, pulling me by the hair and throwing me out. Everyone remembers Karuna-di’s extraordinary performance in that scene, as driven by anger and humiliation she loses all sense of proportion. Just think of the scene: I am wilting under the assault. The cacophony causes Apu to blink. (Shanti-babu made a loud noise with the reflector to make Apu blink. Subir was such a little boy! How could he convey that otherwise?)

Durga and Apu following the confectioner (Srinivas), a dog following them, walking by the side of a pond. Their reflection in the water below, a folk tune in the background. They are going towards Ranu’s house. The dog was not following us properly. So Manik-da gave some eatables in my hand to carry, off camera. The dog now kept to the script.

And who can forget the music by Ravi Shankar? The separate themes he composed were so beautifully fused with the scenes by Satyajit Ray himself. The use of Raga Desh in the scene of Durga and Apu getting wet in the rain, Raga Tori in Durga’s death scene, Raga Patadip on the dilruba when Sarbajaya breaks down while informing Harihar of Durga’s death reveals the director’s knowledge of music and the skill with which he assimilated it in the film.…

Learning from experience, Manik-da probably realized the problems of working with new faces. So, it is said, in his later films he preferred less of new artists. But then Soumitra, Sharmila and Aparna also made their first films with Manik-da. By virtue of their talent, they went on to rule the minds and hearts of their fans. Manik-da was perhaps their philosopher’s stone. And we – from Pather Panchali – still hum the song of the little road.

But there were detractors too. I heard Bhanu Bandyopadhyay never said anything good about the film. Nargis Dutt also made some uncharitable remarks about it. Something like better not to showcase such poverty to the world. But that was the reason why Pather Panchali was felicitated as ‘the greatest human document’. Because the English version of the title was ‘Song of the Road’, Dr Bidhan Chandra Roy perhaps thought the film could be used in depicting community development projects of the government; and that is why the financial help was forthcoming. There are many such stories about Pather Panchali. Even the other day, in a leading newspaper, below my photograph my name was written not as Uma Dasgupta, not as Runki Banerjee (the one who played the infant Durga), but as Rinku Banerjee. Who knows wherefrom they get such news! Many journalists ask such silly questions, that too on telephone, it appears they have neither read the book nor seen the film.

This is how people at every level of society relate to the experience of watching Pather Panchali. They do not allow me to forget the experience. Manik-da felt there were some shortcomings in the picturization of Pather Panchali; that he would correct these given a chance. Despite these shortcomings, even today, after years, Pather Panchali is a matter of pride for all Bengalis.

Translation by Shantanu Ray Chaudhuri.

Originally published in Satyajit Ray-er Pather Panchali, edited by Arun Sen, published by Pratikshan.

Tags

About the Author

.jpg)