Ashok Kumar- The Elixir of Life

In an industry of facile labelling they've called him "the evergreen hero" for the past few decades now a label quite frequently affixed to Dev Anand also. During my early years in film-journalism I came very close to the families of three very great actor stars, and it was wonderful to know them so intimately. One of them was of course Raj Kapoor, the other Dilip Kumar and the third was Dada Muni, Paul Muni, as many humorously declared! I mean, Ashok Kumar.

My very first visit to Dada Muni's home at Rampart Row, high up above S. Rose & Company, the old and reputed house of pianos and other musical instruments, proved to be a memorable one. It happened right at the door when I rang the doorbell.

I had just joined Filmfare then and I'd been assigned to do a story on Ashok Kumar, the first of many I have done over those memorable years of the fifties. So I rang the doorbell and waited. In a few moments an attractive lady opened the door and looking directly at me she got a quite obvious shock. She stepped back, startled and taken unawares as though confronted by someone she least expected to see, and uttered a name in Bengali three or four times, even while retreating into the house and gesturing me to enter.

Dada Muni came downstairs and the mystery of this strange welcome was soon cleared. The lady who opened the door was Shobha, Ashok Kumar's wife, and she had reacted so agitatedly because I looked exactly like her late elder brother and she was so startled she thought that brother had returned to the land of the living to meet her!

Since then our friendship developed rapidly. My wife Krishna became more of a member of the Dada Muni family, a confidante to their teenager children Bharati, Arup and Roopa. Indeed, Krishna's friendship with Bharati and Roopa has endured over the years, to this day.

There is little scope, at this stage of this remarkable star actor's life, to say anything that has not already been said by me or by other journalists, before. So what I'll do instead, is this….

I have before me four foolscap sheets, now yellowed with age. They are filled with the tiny and neat handwriting of the thespian himself, writing about himself. It was a gift from him to me, and it's nearly four decades old. What you are about to read is about Ashok Kumar by none other than Ashok Kumar.

Here goes .. .

I never wanted to become an actor. Twenty two years ago when I came to Bombay, I was a thin lad with a prominent jaw, expressionless eyes, nervous strides, and everything that does not make an actor. I was quite happy as the laboratory assistant at Bombay Talkies where I worked with full zest, day and night to prove my existence as a bread-earner. The 150 rupees that they gave me, I thought, was enough to make my life complete.

For certain reasons, the thin leading man of Bombay Talkies left for Calcutta to join New Theatres, and I do not know yet what prompted Mr. Himanshu Rai to cast me in Jeevan Naiya (1936) opposite Devika Rani. The wise people of the industry who saw me work on the sets were not very wrong when they said: "This boy has a very short life in the field of acting." I didn't care because I was not interested in acting myself, and I went on patiently with the study of laboratory processing.

As it is, Devika looked much older to me as my sweetheart even though she tried all sorts of enamels and paints on her face. I just managed somehow to fire away the lines of my dialogue for I knew that I was just filling the interlude between finding a good leading man for Devika. Her acting talents were ballyhooed to such an extent that in spite of myself, I wondered whether Norma Shearer could ever come near her toes.

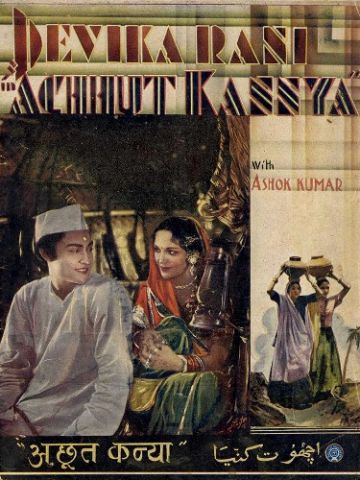

So on the sets of Jeevan Naiya I was only wiping my perspiration, stamping my feet, and scratching my head vigorously. The same continued in Achhut Kanya (1936) except for a significant sentence once uttered by Himanshu Rai that I had a hidden talent somewhere . . . which might take me to eminence.

Twenty-two years ago Indian audiences cared little for good acting. "This innocent looking boy is good enough for us" and so I was forced to stumble along the same old way. I cursed myself for not having taken up the job of Income Tax Officer which my father had wangled for me a year ago. But it was too late, for I had crossed the age limit. I wish now I had become an Income Tax Officer for the sheer joy of summoning Dilip, Raj, Nargis, Nimmi and the Travancore sisters in my cubicle and shouting at them for the timely payment of taxes! But in the realm of God, many a time, situations are reversed.

However, I soon realised that I had somehow got to stick to the hard profession of acting. So I bought some expensive books on acting and started reading them aloud. I mugged up Pudovkin, Stanislavski, Boleslavski and some others and went on the sets of the new picture with the confidence of a champion boxer. But I found to my dismay that Pudovkin never mentioned a word about the kind of scenes that I had to do! So I had no defence and Devika pummelled me with hooks and uppercuts till Franz Osten, the German director, counted me out.

In 1939 the war broke out and all the German technicians of Bombay Talkies were sent to the Sattara camp. In 1940, Himanshu Rai died and my all-time colleague S. Mukerjee was given the charge of production. He, being married to my only sister, for purely selfish and nepotic reasons, thought of making me a star!

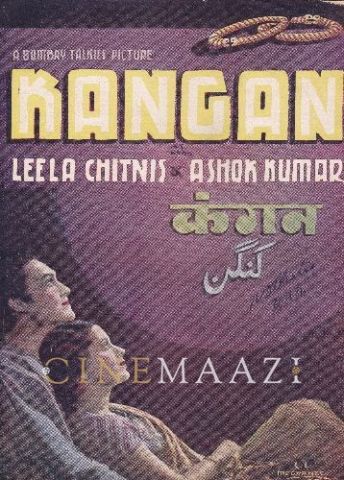

He sat down with story writers and prepared in quick succession scripts like Kangan (1939), Bandhan (1940), Jhoola (1941), Naya Sansar (1941), Kismet (1943) the productions which in later years, were to become legends as box-office hits. I myself was surprised when I was hailed as a box-office star and Sasadhar looked at me with the pride of 'a star-creator! He used to come on the sets every minute, and not only explained to me how to act, but also acted the scenes himself for me!

I still wonder: when did he learn to act or write? During this time Rai Bahadur Chunilal, who loved me as a close relative, was a great help to me in building up my career. During these years also Gyan Mukherjee, the science scholar from Allahabad, was marking time to discover new fields in films for the box-office.

In 1943 for very selfish and personal motives, the Bombay Talkies unit broke up. We left the Bombay Talkies in a group and somehow managed to start a film producing concern called Filmistan, little realising that in later years it was to become the most successful concern in film-commerce.

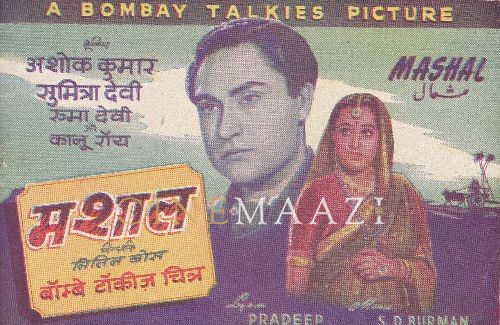

In 1946, for purely sentimental reasons, I left Filmistan with Savak Vacha, to pep up the dwindling condition of Bombay Talkies. It was a Herculean task since between 1943 to 1946 Bombay Talkies was deeply in debt to the fantastic figure of 28 lakhs. The management between 1943 to 1946 must have been very slipshod. We made a number of pictures to stem the tide of destruction. Majboor (1948), Mashal (1950) and Maa (1952) fared quite well at the box-office but the deficit could not be made up, and Bombay Talkies folded up for good.

It was during the years 1946 to 1953 that I came to a realisation that life was not so simple and easy as I had taken it to be. If you are little off-guard, you are sure to get a sneak blow from the most unexpected quarter. Any documents you sign can be twisted against you and can land you in the High Court. A trustworthy man without any provocation can be very untrustworthy for selfish reasons. It was thus that in trying to help my so called friends I messed up my own life. I started behaving differently, thinking at all times "beware of Brutus!" But Brutus is discovered only after he has stabbed you so I don't know how many Brutuses I have yet to meet.

Gyan Mukerjee's eyes were watching me. He must have been quite fascinated by my mental condition to have written the gangster story Sangram (1950) and star me in it. The public acclaimed the picture with a new zest that I was best with a live revolver in hand, firing away my way through life. The exhibitors and the distributors demanded from the producers to star me in more gangster pictures, killing people out of spite, yet at the same time, not losing public sympathy. Life is complicated.

More than two decades have passed since my advent in films. In moment of leisure when I sit back with my pipe in mouth, I see before me the third batch of leading artistes raise their proud heads.

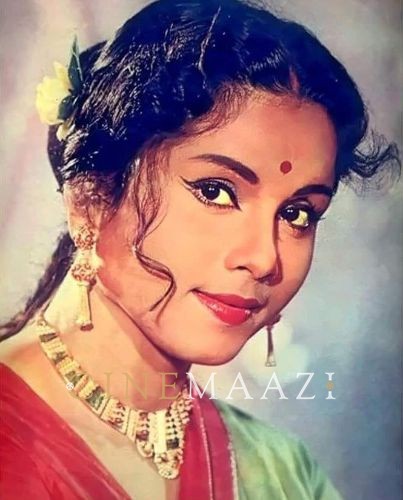

I fondly see my youngest brother Kishore, nineteen years younger than me, strutting along the front line with more zest than I ever had. I am assured to see the three year old baby of yesterday, starring with me in a series of pictures. I sit back with fond remembrances of Devika Rani and Leela Chitnis. I am a little sad when I think of my friends Saigal and Chandra Mohan who have passed away into the land of peace. I remember with tears my colleague and playmate for over forty years Arun Kumar breathing his last in my arms.

Friends ask me with a twinkle in their eyes "How many years more?" I only smile at them. I have not yet discovered the elixir of life.

This piece is signed by Ashok Kumar and dated December 9, 1955.

This article was originally published in Bunny Reuben's book Follywood Flashback. The images used in the feature are taken from the book and Cinemaazi archive.

.jpg)