The Glory Days of the Progressive Writers' Movement and the Bombay Film Industry

Hum akele hii chale thhe jaanib-e-manzil magar

Log saath aate gaye aur karvaan banta gaya

– Majrooh Sultanpuri

Several Urdu writers came to Bombay all through the 1940s to find work in the film industry – as scriptwriters, lyricists, film journalists – and met with varying degrees of success. Josh Malihabadi, Akhtar-ul-Iman, Krishan Chander and Saghar Nizami were in Poona (where most of the film studios were initially located), but the lure of the silver screen drew them to the city that was fast becoming home to the biggest film industry in Asia.

By the time the Second World War ended, some of the most dynamic writers of the age had flocked to Bombay from different parts of undivided India: among the Urdu writers there were Rajinder Singh Bedi, Hameed Akhtar, Sardar Jafri, Kaifi Azmi, Jan Nisar Akhtar, Majrooh Sultanpuri, Rifat Sarosh,Niyaz Haider, Hajra and Khadija Masroor, Saadat Hasan Manto, Miraji, Vishwamitra Adil, Ismat Chughtai and her husband Shahid Latif to name a few; Hindi writers included Upendranath Askh, Nemichandra Jain, Amritlal Nagar, Balraj Sahni, Prem Dhawan; Marathi writers Mama Warerkar and Anna Bhau Sathe; and Gujarati writers Bakulesh Swapnath and Bhogilal Gandhi.

Thereby hangs a tale, but to reach these glory days, we must go back in time and look at, first, how and why the gathering of literary talent took place in one city and then the possible reasons for its dramatic flowering through the mass medium of popular films.

If we were at look at events sequentially, there was the Russian Revolution of 1919; the formation of the Communist Party of India (CPI) on 26 December 1925; the publication of Angarey, a collection of the first-of-its-kind anthology in December 1932 and the subsequent ban on it in March 1933; the drafting of the Manifesto of the still-to-be-launched PWA in Nanking Restaurant, London, on 24 November 1934; the publication of a long essay, ‘Adab aur Zindagi’(Literature and Life) by Akhtar Husain Raipuri in Maulvi Abdul Haq’s journal Urdu, in July1935, spelling out the place of realism in life, and by extension, all forms of art; the publication of the Hindi version of the Manifesto by Premchand in his journal Hans, in October 1935, thus reaching a very large section of Hindi readers and writers; a conference of Urdu–Hindi writers in Allahabad organized by the educationist Dr Tara Chand in December 1935 which paved the way for the progressives to meet on a common platform; the first meeting of the All-India Progressive Writers’ Association (AIPWA) where Premchand delivered his seminal inaugural address entitled ‘Sahitya ka Uddeshya’ (The Aim of Literature), on 9 April 1936 in Lucknow, outlining the aims and objectives of progressive writing and urging fellow writers to change the ‘standards’ of beauty; the tenure of P.C. Joshi as general secretary of CPI from 1939 to 1948 and its implications for culture, literature and the performing arts given Joshi’s understanding of how all art could be used as a soft tool for the dissemination of ideas; World War II (1939–1945), when the progressives joined the war effort which was billed a ‘people’s war’; the lifting of the ban on the CPI(1942–46) when it became the third-largest political party in India; launching of the Quit India Movement in August 1942 by Gandhi-ji which was the largest mass movement India had yet witnessed, one that brought people from different sections of society together and infused a spirit of egalitarianism, nationalism and fostered a sense of common cause.

Returning to Bombay, 1943 proved to be a crucial year. The first All-India Congress of the CPI took place in Bombay in May 1943. An equally important event occurred in its sidelines. The Fourth AIPWA met in the Marwari Vidyalaya and the Indian Peoples’ Theatre Association (IPTA) was born. Also, the central office of the PWA moved from Lucknow to Bombay and the course and content of the movement increasingly began to come from a group known as the ‘Bombay Progressives’. Also, Sajjad Zaheer, the powerful progressive ideologue, who had been in prison till 1942, moved to Bombay where he took charge of the PWA along with Sardar Jafri, Sibte Hasan, Kaifi Azmi and others. A host of Urdu journals, both film magazines as well as literary ones, and also the People’s Publishing House, which gained an envious reputation of printing large copies of inexpensively priced high-quality books, soon put Bombay on the literary map.

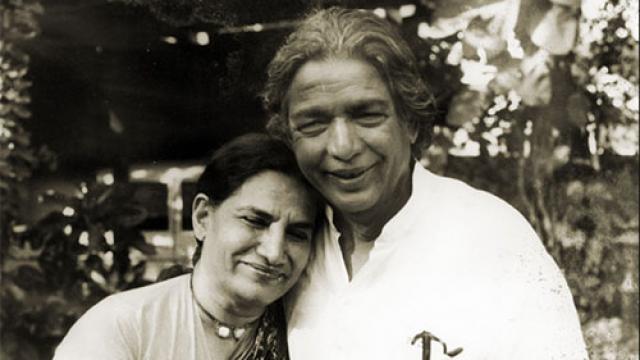

It is to this Bombay – brimful with new ideas, a hub of the country’s best minds, a melting pot of young people from different, far-flung regions, busy pouring new wine in new bottles – that Kaifi Azmi, a full-time party member, brought his Hyderabadi bride, Shaukat Azmi, to live in the commune in Andheri. Shaukat noted her first impressions thus: ‘Katthal, banana and mango trees stood with giant banyans. A swing was hanging from one of the trees and the air was filled with the scent of mogra and juhi. A few years earlier, this idyllic setting had been the home of the Cultural Squad, a wing of the Communist Party. Many artists and dancers had lived here … In 1943, during the Bengal famine, artists from the Communist Party of India had toured the length and breadth of the country and collected two lakh rupees for relief work. Their theme song, “Bhuka hai Bangal” (Bengal Is Hungry), written by Wamiq Jaunpuri, became very well known throughout India. We went to Kaifi’s tiny room in which there was a loosely strung jute charpai with a dhurrie, a mattress, a sheet and a pillow. In one corner there was a chair and a small table on which there were some books, piles of newspapers, a mug and a glass. The simplicity of this room touched my heart…’

Shaukat describes Kaifi and his friends, who would become her fellow-travellers, thus: ‘They were enlightened and humane individuals who were struggling to create a new world for the poor, the destitute and the hungry. Although they were from different parts of India, these people were like one family where everyone was addressed as “Comrade”, which at the time meant an evolved human being.’

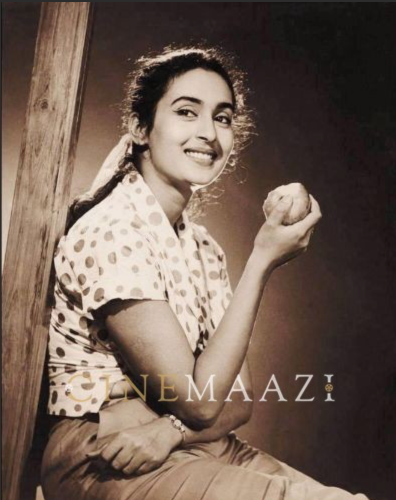

Kaifi earned Rs 40 as monthly salary from the Party; from this he had to give Rs 30 towards his wife’s boarding expense. To earn some extra money, he wrote a column for the Urdu daily Jamhuriat. Partly to lighten the burden on Kaifi and partly in response to P.C. Joshi’s command that ‘the wife of a communist should never sit idle’, Shaukat got drawn into the IPTA. Her first role was in Ismat Chughtai’s Dhani Bankein (Green Bangles), a play on Hindu–Muslim riots that were tearing the fabric of a newly independent India. Here, Shaukat got drawn into the country’s most vigorous cultural movement that had the likes of Zohra Segal, Uzra Butt, Bhishm Sahni, Prithviraj Kapoor, among its stalwarts.

The IPTA, PWA and the Bombay film industry were like three interlinked circles, with overlapping memberships and a host of common concerns. Foremost among these concerns was a socially transformative agenda which would fulfil the needs of a fledgling nation. For this they sought inspiration not only from Marxist tomes and ideologues but also from Nehruvian socialism that hailed schools, colleges, dams and factories as the ‘temples of modern India’.

Members of IPTA and PWA – some of whom worked in the film industry as actors, directors, scriptwriters, lyricists, technicians, etc. – operated in tandem to produce a radically new set of images, metaphors, vocabulary, even aesthetics that influenced several generations of film-goers. Their most visible and immediate effect was the introduction of a non-sectarian ethos, one that rose above the narrow confines of caste, creed and religion and worked as balm on a national psyche that had been traumatized by the communal outrages before, after and during the partition.

Apart from Shaukat Azmi’s account, we find several other memoirs that talk of this important period. There is Akhtarul Iman’s Iss Aabad Kharabe Mein, Rafat Sarosh’s memoir Harf Harf Bambai: Ta’assurati Khake, Ibrahim Jalees’s Bambai, as well as essays by Ismat Chughtai and Saadat Hasan Manto. While Manto is acerbic about the progressives given his love–hate relationship with most of his fellow writers, Ismat describes the Bombay progressives as a group of ‘undisciplined revolutionaries – careful, happy-go-lucky and very interesting people. I remember spending very exciting moments in the company of these outspoken, candid, crazy but intelligent people.’ Typically her interest in them was on grounds of compatibility and camaraderie rather than party affiliations, even less so on any real understanding of the CPI’s policies, let alone how and to what extent they had begun to influence the working of the Bombay group: ‘I have never seriously taken it to be my mission to reform society and eliminate the problems of humanity; but I was greatly influenced by the slogans of the Communist Party as they matched my own independent, unbridled, and revolutionary style of thinking…What wonderful get-togethers, arguments and scuffle of words we had!’

Bombay became a melting pot where writers were writing rousing poetry asking the people of Asia and Africa to arise, to fight a common enemy and make common cause with a host of issues, be it anti-fascism, anti-colonialism, anti-imperialism as also nationalism, feminism, land reforms, widow remarriage, social inequalities, economic exploitation, and so on. There was something in the very air of Bombay that was redolent with the need for change and progress. Regardless of their sympathy for communism per se, there was no shortage of writers who saw the merit of purposive literature and were prepared to find common ground with the progressives despite their reservations about organized communism.

*

Among the Bombay progressives, the one person who gained the most name and fame, not to mention top billing and a fortune, was Sahir Ludhianvi. His lyrics in simple but chaste Hindustani touched a chord with millions of Indians in films like Pyaasa (1957). Till the early 1950s, his reputation rested largely on his progressive poetry for the mushaira circuit since his first collection entitled Talkhiyan (Bitterness, 1943) had earned him instant recognition as the voice of an entire generation. In later years, he came to be regarded as a lyricist rather than poet and, like most progressives, learnt to make compromises by giving in to the demands of film-makers– a practice Kaifi once compared with digging a grave and then looking for a corpse to fit it given the fact that not only is the context pre-decided but so is the tune!

Aao ke aaj ghaur karein iss sawal par

Dekhe thhe humne jo vo haseen khwaab kya huwe

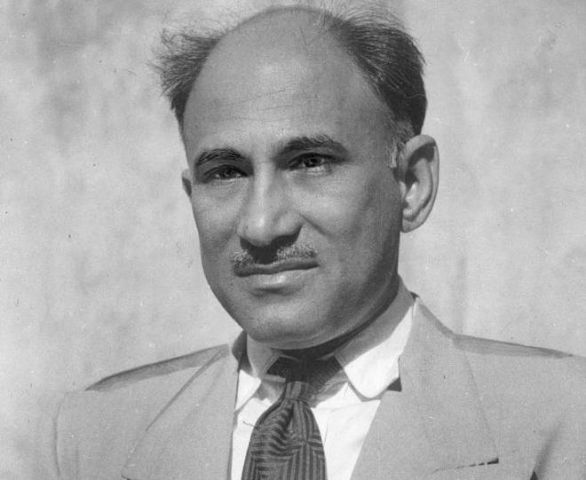

Members of the PWA were not living in a bubble; they were actively involved in the cultural life of the city and the political life of the nation. Khwaja Ahmad Abbas (1914–87), for instance, was an active member of the Aligarh branch of the PWA during his student days who graduated effortlessly to becoming an integral part of the Bombay progressives’ group during its glory days. Active in IPTA and the Bombay film industry as well as being a prolific novelist, short-story writer and journalist, he made several important films like Saat Hindustani (1969) and Do Boond Pani (1972). Neecha Nagar, based on a story by Hayatullah Ansari, won him the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film festival in 1946 though it was Dharti ke Lal, in the same year, his first directorial venture that saw a comingling of several talented progressive writers. Jointly written by Abbas and Bijon Bhattacharya, based on plays by Bhattacharya and the story ‘Annadata’ by Krishan Chander, it had music by Ravi Shankar with lyrics by Ali Sardar Jafri and Prem Dhawan, and was a clear-sighted look at the Bengal famine.

Abbas had gained fame for writing the hugely popular column ‘Last Page’ in 1935 for the Bombay Chronicle and when it closed in 1947, he moved the column to Blitz where it continued till his death; it was known as ‘Azad Kalaam’ in the Urdu edition.

Like Abbas, Kaifi Azmi straddled the word of literary journals and films. In 1948 he wrote his first lyric for the film Buzdil, directed by Shahid Latif, the husband of his friend and fellow progressive, Ismat Chughtai, and went on to write some of the most hauntingly evocative lyrics ever written for the Bombay film industry including the memorable ‘Waqt ne kiya kya haseen sitam…’ An ardent member of the PWM and a major crowd puller at the peoples’ mushairas organized by the progressives in industrial hubs such as Bhiwandi, Kaifi was equally active as a spokesperson for several workers’ unions. A writer of tender lyrics and rousing anthems displaying an astonishing combination of passion and conviction, Azmi was the quintessential activist-poet. His three major poetry collections are entitled Jhankar (1943), Akhir-e-Shab (1947) and Awara Sajde (1973). Others who bridged the gap between literature and cinema were Kanhaiya Lal Kapoor, Ramanand Sagar, Kaifi Azmi and Akhtarul Iman. Not all, however, reached the heights scaled by Sahir. Majrooh Sultanpuri, for instance, wrote his first lyrics for the film Shah Jahan in 1946 and then launched upon a highly lucrative career in Bombay. However, his leftist leanings did not leave him entirely and in 1949, Morarji Desai, the then governor of Maharashtra, sent him to jail for two years (along with the actor and IPTA activist Balraj Sahni) for writing poetry that was perceived to be against the Nehru government. Majrooh recited the poem at a meeting organized for mill workers, and subsequently refused to tender an apology.

Makhdum Mohiuddin, fiery trade union leader and writer of romantic verse and fiercely political poetry, never wrote for films though several of his ghazals were used in films.

The writers and lyricists occasionally also dabbled in making movies with mixed results. For instance, along with fellow progressive Vishwamitra Adil, the maverick writer Niyaz Haider wrote the lyrics for Sarai ke Bahar (1947), the only film directed by prose stylist Krishan Chander.

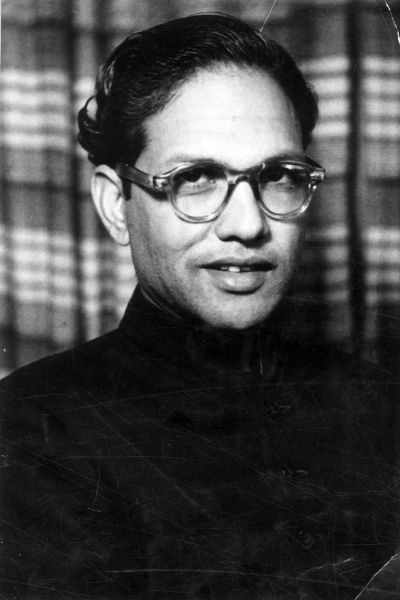

Rajinder Singh Bedi (1915–84), however, fared better than most. Beginning his professional life as a postal clerk, Bedi moved to Bombay as an established fiction writer and got involved with the film industry like many of his fellow progressives but his diverse interests led him from writing the dialogue and screenplay of over twenty-seven films to producing and directing memorable films such as Garm Coat (1955), Dastak (1970) and Phagun (1973).

As the PWA grew, its younger sibling, the IPTA, spawned a host of cultural squads. PWA functions became lively, energetic occasions with songs and dances interspersed with academic discussion and poetry readings. The progressives wrote plays and songs which were shown to peasant and working-class as well as middle-class audiences in different parts of the country. Cross-fertilization between the PWA, the IPTA and the film industry gave rise to an exceptionally robust kind of cinema. Taking a cue from the progressive writers, many progressives as well as others who were at best ‘fellow travellers’ began what one can only call a process of systematic ‘seeding’. Progressive ideas were seeded in the cinematic oeuvre where they found fertile ground; some flourished and flowered dramatically, reaching the nooks and crannies of popular imagination; others made it big on the film festival circuit and scored among elitist film critics but did not always find a favourable response among the general Indian public, let alone a release in mainstream movie halls.

It must also be noted that the glory days of the PWM in Bombay also coincided with the most tumultuous period of modern Indian history – Gandhi’s call to satyagraha, India’s response to the rise of fascism, the Second World War and its impact on India, the Bengal Famine, Independence, Partition and the communal disturbances that scarred the nation and the wars with Pakistan and China. The Bombay progressives faithfully reflected each of these momentous events that shaped the nation’s destiny; at the same time, they drew the nation’s attention to events outside the country such as the Rosenberg Trial, events taking place in Russia, the decolonization of Africa and Asia, and the emergence of a new world order in which India sought its rightful place.

The hegemonic ideological force of the PWA in Bombay did not dissipate overnight. The coming of Independence saw the departure of many writers to Pakistan. The flock dwindled, many of the progressive journals closed down and Urdu itself shrunk in importance as a lingua franca. Those who remained within the progressives’ fold increasingly found no reason not to respond to Nehru’s call and join the nation building project. Then, in purely literary terms, there was the rise of another literary movement – the modernist movement – that spoke of the inner life, the life of the mind. The PWA, as it had existed in all its glory and might all through the1940s, became a shadow of its former self.

While the Bombay progressives may have weakened as a literary grouping, their influence continued to be felt for a very long time in the work of film lyricists. For instance, the IPTA poet Prem Dhawan wrote in Hum Hindustani (1960):

Chhorho kal ki baatein, kal ki baat puranii

Naye daur mein likhenge hum milkar nayi kahani,

Hum Hindustani, Hum Hindustani…

In B.R. Chopra’s Naya Daur (1957), we see Sahir exhorting his fellow countrymen and women – almost in Soviet style – to join hands, put their shoulder to the wheel and build a new and prosperous India:

Saathi haath badhana saathi re

Ek akela thak jayega, milkar bojh uthana…

And in Dhool ke Phool (1959) there is Sahir again exhorting them to put communal ill will aside and, in true Nehruvian style, become a liberal humanist:

Tu Hindu banega na Musalman banega

Insaan kii aulad hai insaan banega

Kaifi Azmi, a committed card-carrying member of the CPI who found success as a film lyricist and as a published poet, spoke for an entire generation of progressives when writing for films such as Apna Haath Jagannath (1960):

Apne haath ko pehchaan…

Haath uthhatey hain jo kudaal, parbat kaat giratey hain

Jungal se khetii ki taraf morhke dariya latey hain

Zulm hadd se badheyga toh ghatt jayega

Apni talwaar se aap kat jayega...

Yuun badho jaisey lehrake dhaara badhey

Thokrein khaaye toh dil hamara badhey

And in the same film:

Faasle sab dilon ke mitaatey chalo

Apne seene se sabko lagatey chalo

In Naunihal (1967), Kaifi celebrates the enduring legacy of Nehru whom he has long admired with this ode to Nehru’s liberal humanism which he believes is a balm that a country scarred from the Partition desperately needs:

Meri awaaz suno, pyaar ka saaz suno...

Kyun sajaii hai yeh chandan ki chita mere liye

Mai koi jism nahiin hoon ke jala dogey mujhey

Raakh ke saath bikhar jaaoonga main duniya mein

Tum jahaan khaaoge thokar wahiin paogey mujhey

It is this kind of writing that bridges the gap between poetry and lyric, that blurs the distinction between ‘high’ and ‘low’ literature, and ‘popular’ and ‘pedestrian’, that limns wisdom with empathy that is the progressives most valuable gift to Hindi cinema.

Tags

About the Author

Dr Rakhshanda Jalil is a translator, writer and literary historian. She has published over twenty-five books and written over fifty academic papers and essays. Her book on the lesser-known monuments of Delhi, Invisible City, continues to be a bestseller. Her recent works include Liking Progress, Loving Change: A Literary History of the Progressive Writers Movement in Urdu (OUP, 2014); a biography of Urdu feminist writer Dr Rashid Jahan, A Rebel and her Cause(Women Unlimited, 2014); a translation of Intizar Husain’s seminal novel, Aage Samandar Hai, on Karachi, The Sea Lies Ahead (HarperCollins, 2015) and Krishan Chander’s partition novel Ghaddar (Westland, 2017); an edited volume of critical writings on Ismat called An Uncivil Woman (Oxford University Press, 2017); and in the past year a literary biography of the Urdu poet Shahryar for HarperCollins; The Great War: Indian Writings on the First World War (Bloomsbury); Preeto & Other Stories: The Male Gaze in Urdu (Niyogi) and Kaifiyat, a translation of Kaifi Azmi’s poems for Penguin Random House and Jallianwala Bagh: Literary Responses in Prose &Poetry (Niyogi Books). Her latest book is But You Don’t Look Like a Muslim (HarperCollins), a collection of forty essays on religion, culture, literature and identity. She runs an organization called Hindustani Awaaz, devoted to the popularization of Hindi–Urdu literature and culture. Her debut collection of fiction, Release & Other Stories, was published by HarperCollins in 2011, and received critical acclaim. She has received the Kaifi Azmi Award for her contribution to Urdu and the First Jawad Memorial Prize for Urdu–Hindi Translation. She writes regularly for major newspapers such as Hindustan Times, Indian Express, The Hindu as well as magazines such as Outlook, Scroll, The Wire, etc. She is the editor of the Taj magazine, a biannual book-length journal of the Taj group of hotels.

.jpg)