The First Two Decades of Bengali Film Music: The Silent Era

Let’s reconstruct a music session of Bengali silent cinema. The sources of information used here are the memories – set in social and historical contexts – of a number of people keenly associated with Bengali culture. The family of Salil Chowdhury, the iconic film-composer, is a treasure trove of reminiscences of the music used in silent Bengali cinema. Nikhil Chowdhury, the elder brother of Salil Chowdhury, was a regular participant in the live concerts played for it. Salil, at times, played a couple of notes on the piano during live music sessions in movie theatres. ‘Milon Parishad’, Nikhil Chowdhury’s band, had a contract with Chhaya, a north Calcutta movie theatre, for regularly playing live music during the screenings of silent cinema. The elder brother – who died young and unsung – sowed the seeds of film music into young Salil’s fertile mind and, thus, enriched Indian film-music as a whole.

The rule was broken only when a theatre could tempt a famous musician to come to a screening. In that case, the musician was presented as a star. The spectators would also come to see him, along with the movie stars on the screen. Byron Hopper, who played an instrument called ‘cinema organ’ at Madan Cinema (Palace of Varieties), was one such star. Madan used to release daily advertisements in The Statesman declaring the music he would play ‘today’. But, as Salil Chowdhury said, Bengali musicians were not that privileged.

The ornamental pieces, however, were not long enough to fill the entire length of a silent Bengali film. In short, the music was never complete. We can easily understand the meaning of ‘complete music’ if we remember operas like Magic Flute (Mozart) and Chitrangada (Tagore). Not even a stretch of 10 seconds was left silent. The music of Battleship Potemkin, Metropolis and Modern Times – all silent films – still enthrall us. In Bengal, empty stretches were left between the pre-composed tunes. Those stretches were filled up with improvised musical effects, leaving little space for truly silent passages during the screenings.

Instruments like the sitars and the sarods were sparsely used for background music, as it was believed that Indian instruments were meant only to be played solo. Film-makers of the era generally preferred (though the numbers would vary):

• Three violins and one viola

• Two clarinets – b flat & a

• Two sets of large cymbals

• A set of wooden flutes

• A piano

• A cello (rarely)

• A double bass (rarely)

• Organ (not in all theatres)

An unusual fusion was often achieved when khol, a percussion used by the Vaishnava sect, replaced cymbals to make the accompanying music more suitable for mythological films.

Now we will attempt to explain the ‘tone colours’ (timbres) envisaged for the music of the silent Bengali films. And why were the chosen timbres indispensable.

First, one point should be taken into account in this context. The main rival of Bengali silent cinema was jatra (the folk drama of Bengal). It’s rather easy to understand why, if we study the themes chosen for silent Bengali films. Almost 70 per cent of the film themes – like jatra – were mythological. As such, both jatra and cinema were targeting the same audience.

To answer the question, we must try to identify the most dominant building block of the jatra. It was undeniably the long monologues and dialogues. Often composed in verses, the spoken lines of jatra melodiously danced on the three musical scales when recited by accomplished actors. It was the poetic dialogues – mostly written in an archaic Bengali in keeping with the mythological characters – that enthralled the audience for centuries. Thousands of villagers would happily spend entire nights watching jatras being performed on open fields in late autumn.

On the other hand, silent cinema was totally bereft of spoken words. This was a challenge that the film-makers had to contend with. How could they respond to this?

They decided to depend on the second dominant component of folk theatre, i.e., loud music. Three European/global instruments were profusely used in jatra to hold the attention of the audience. Why did these three dominate silent Bengali cinema?

Let’s go back to the roots.

With the arrival of Portuguese traders in the early sixteenth century, people in Bengal were getting acquainted with European music. Bengalis started to understand a few features of European music – the value of counterpoints, for instance.

The violin became popular in regions as disparate as Bandel (a small town on the bank of the Ganga) and Chittagong (a port on the shore of the Bay of Bengal). Churches as well as social gatherings of Portuguese settlements also played a part in popularizing the violin. Why was the violin readily accepted in Bengal? We can hint at two reasons.

1. The striking affinity of the tone colours between the violin and the sarinda, a folk instrument of Bengal.

2. The timbre of a solo violin could closely approximate human weeping, which was one of the main expressions of the collective subconscious of Bengal oppressed for centuries. That’s why death scenes in jatras, theatres and films – with a very few exceptions – have always been underlined by the cohesive outbursts of high-pitched violins. It has often been said that ‘Bengal weeps in the voice of violin’.

The second Western instrument popularized by circuses, jatras and rural bands was the clarinet. The timbre of the solo clarinet is a mysterious fusion of joy and sobbing of a forlorn and helpless orphan. It was, tragically, a familiar sound in rural Bengal due to the perpetual famines. Therefore, the clarinet started conveying the mind of the oppressed that made the bulk of the jatra audience.

The cymbal, used in the Buddhist monasteries of Sikkim and Chittagong as well as in the European operas popular in Calcutta, was also a popular instrument in jatras. Why?

Cymbals convey suddenness. They create a sound that underlines the impact of a specific historical incident imposed suddenly on an unprepared mass.

Therefore, the continuation of cymbals in the Bengali silent films was a fait accompli.

These three instruments were smoothly assimilated in the musical tradition of Bengal and were played in a style that was quintessentially Bengali. So the unsettling question of European hegemony didn’t bother Bengali composers working for jatra, theatre and silent cinema. Violins and clarinets were unabashedly played in the rallies organized by Rabindranath Tagore, on 5 October 1905, against the partition of Bengal.

Ironically, the style of music considered suitable for silent Bengali cinema persisted till the end of the twentieth century. Composing only a few short musical pieces for the entire film was the style discovered for Bengali silent films. Long and complete music was totally shunned. Here is a great example.

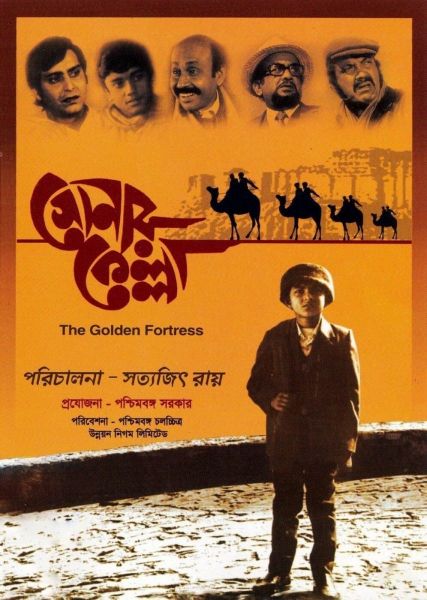

Satyajit Ray composed only four short musical pieces (ornamentations) for Sonar Kella! Only four! The ‘Camel and Train’ music was a legendary ornamentation composed for Sonar Kella.

Minimizing the number of musical pieces was a lesson learnt from Bengali silent cinema.

Tags

About the Author

Ujjal Chakraborty is a National Award winning writer, filmmaker, script-writer, artist and scholar who has been involed in various media fields for over 40 years. He studied Drawing, Painting, Designing and Communication/Commercial Art from Govt. College of Arts & Crafts, Kolkata. He studied Mass Communication, Animation and Modern Film Technology from Magica Institute in Rome, Italy. He has closely worked with Satyajit Ray for over twenty years. He is the author of The Director's Mind: On the Techniques of Filmmaking, Panchali Theke Oscar, Satyajit-Bhabna, Juddher Gyan, Satyajit Ray-er Chalachitrey Choritro-chitron and over 300 essays and research papers on cinema that have been published in various commercial magazines. He has held research positions in the National Film Development Corporation, Ford Foundation, Indian Institute of Chemical Biology and Asiatic Society. He is a regular faculty of Animation Films in the Indo-Italian Institue of Films & Mass Communication, Kolkata. He has also made five short films for the Govt. of Italy.

.jpg)