Bimal Roy: A Daughter Remembers

Subscribe to read full article

This section is for paid subscribers only. Our subscription is only $37/- for one full year.

You get unlimited access to all paid section and features on the website with this subscription.

Not ready for a full subscription?

You can access this article for $2, and have it saved to your account for one year.

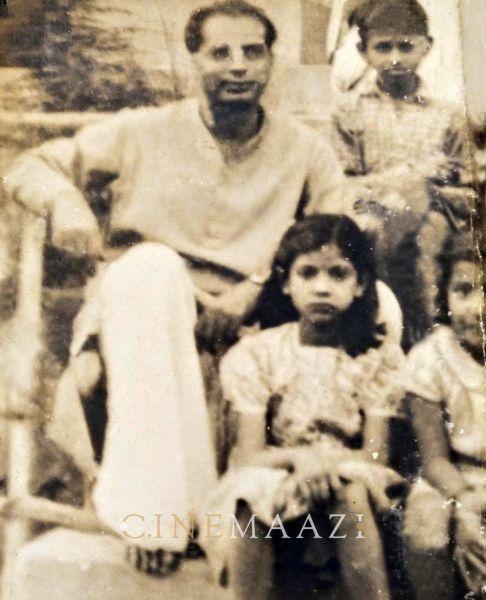

There is very little information available on my father, Bimal Roy. According to the Screen Yearbook 1956, my father's date of birth is 12 July 1909. Family elders argued but since no other record exists, we settled on that. Those who could share stories on the early chapters of his life have long ceased to be. Writing an elaborate biography, sadly, does not seem a remote possibility. Then there is the additional risk – writing the biography of one's parents may inevitably lead the writer into the realm of the autobiography.

Thinking of my father, what I immediately recall is the silent film he liked to watch. As if we are both caught in a timeless wrap, watching the film together, repeatedly. My earliest exposure to cinema was watching films at home. The projector's familiar whirr made us leave dinner midway, rush to the drawing room of our Calcutta home at P 92 Sardar Sankar Road. Meanwhile, Baba had returned home quietly. He was busy setting up the second-hand 16mm projector acquired from the Army disposable lot. The blank wall was a picture screen. We girls sat on the floor waiting excitedly for moving images to pour out from the whirring machine behind. The wall filled with images of a ship surrounded by a group of agitated sailors. Hoping to see fairies or Donald Duck, these mute images of angry sailors disappointed us as did Baba's choice of film. Sailors assembled before a hanging leg of meat crawling with maggots that sparked the October naval mutiny in Battleship Potemkin. For us children, it was a horrible movie. Baba watched Battleship Potemkin every other night with undivided attention! I concluded, naturally, that there was something wrong with my father to like such a horrific film. Decades later, after Baba had passed away, his fascination with the film struck a chord. His generation had learnt about the new medium of cinema by watching celebrated world maestros. Baba's meditative viewing sessions were a lesson in self-orientation. Without any overt effort on his part, he had managed to initiate us into the world of sound and picture.

What I also remember overhearing is that father was going to be adopted by his childless uncle Jogeshchandra Roy. Apparently, his formal adoption was stalled at my grandmother's request. One is not sure of the credentials of the adoption story. However, if a senior relative is to be believed, the Suapur zamindars lived the life of indolent feudal lords. 'There were at least a hundred people to feed daily,' boasted an uncle recalling our huge joint family.

The same uncle mentioned that most evenings in the Suapur estate were spent at the kotha baari adjacent to our house. Singers and nautch girls were hired to entertain the zamindars all night. The two brothers, Hemchandra and Jogeshchandra, were obviously fond of the good life. This included branded Scotch whisky flowing freely during nocturnal sessions. My father's strong aversion to alcohol may have originated from this. He never drank, and it was a taboo in our home to even mention it. The Bimal Roy home, in that sense, had the least filmy pretentions in the entire Bombay movie industry.

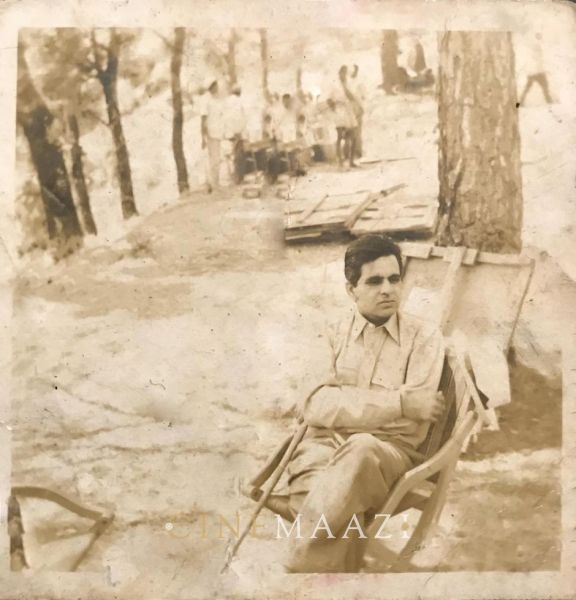

There was every bit of the ordinary Bengali bhadralok in Baba. He woke up early before the rest of our household even stirred. Made his cup of raw tea with a slice of lime. Took a leisurely walk in the garden. During the walk, he plucked seasonal vegetables from our patch. When we woke up, he would show off a cabbage, pumpkin or papaya beaming with paternal pride. His lifestyle was simple, regular and uncomplicated – even boring one may add – compared to the rich and famous homes of the big movie world.

.jpeg/WhatsApp%20Image%202020-05-12%20at%204_04_56%20PM%20(1)__523x600.jpeg)

Oddly enough, Baba's films throw up situations and characters easy to identify from his own life. The lush pastoral landscapes of village life is etched by evocative strokes as the camera dwells indulgently on mango groves casting long shadows across the land. The soundtrack picks up plaintive calls of mating cuckoos echoing love songs or the boatman's haunting melody that completes the rustic imagery.

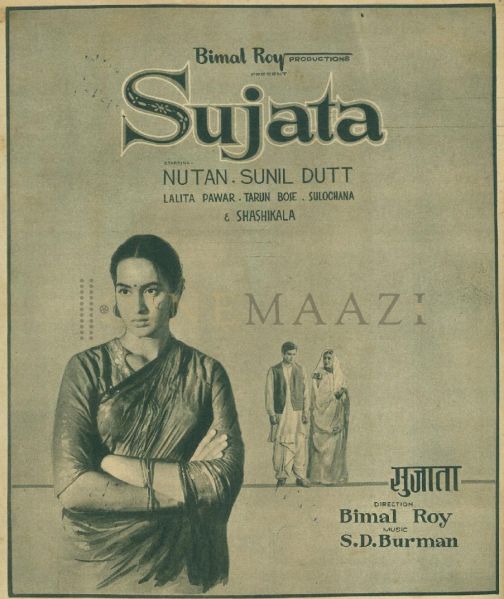

I have often thought it is not difficult to reconstruct Baba's life with scenes from his films. The genteel portrait of Sujata's affectionate foster father, Upen, for example, comes close to Baba. This is true of the postmaster father Nivaran (Parakh). His silent bonding with his daughter Seema is no empty gesture. Take the case of his decision to film Tagore's Kabuliwala. The latter's yearning for his little daughter in distant Afghanistan clearly establishes Baba's profound regard for enduring human relations, essentially, his faith in lasting family values.

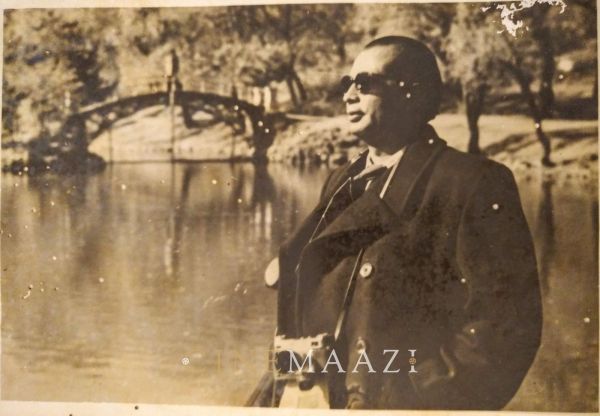

In every sphere of his life, it was evident that Baba was a proud Bengali ... his partiality to our traditional cuisine, his choice of wardrobe, theatre, his passion for football matches. Photographs from his Moscow trip in bitter winter show him in spotless dhuti kurta. Being an enthusiastic gourmet, Ma trained a retinue of chefs with fine dining skills. Home lunch was sent daily to Mohan Studio in Kurla. So popular were its contents that his tiffin carrier grew visibly larger.

Once, Dilip Kumar was invited home for dinner. He relished the feast greatly, complimenting Ma in chaste Urdu. Before leaving, he asked Ma her secret of filling the right amount of air into each puri! Ma almost fell down laughing and Dilip Kumar's query about the puri remained ma's favourite joke.

I am often asked how my parents met. Ma was studying for her matriculation in Ramnagar. Baba was working in Calcutta. The link came through Baba's sister, who was married to ma's uncle, a surgeon in Banaras. Baba would visit his sister who did not waste time to play matchmaker. The rest is history. My parents married in 1933. Their Calcutta reception was a star-studded affair. Indian cinema's royalty – P.C. Barua, Kanan Devi, Pankaj Mullick, K.L. Saigal, R.C. Boral, Nitin Bose – were present to bless the newly-weds, Mrs Nitin Bose proudly informed me.

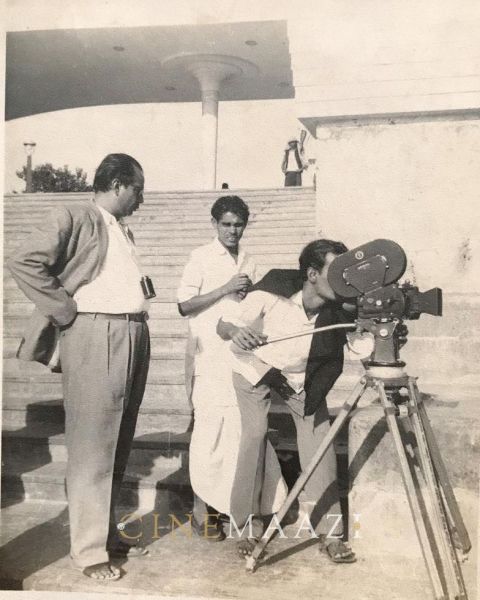

Rarely has any film banner displayed the name of a cinematographer on the billboard. This phenomenon happened with P.C. Barua's Mukti. Filmfare editor B.K. Karanjia observed: 'After a period of apprenticeship under Nitin Bose, a Dacca-born cinematographer, Bimal Roy, was put at the helm in Daku Mansoor (1934). A string of films followed, including Devdas, Manzil, Maya. But it was the evocative outdoor camerawork for Barua's Mukti that made Bimal Roy a star.' The name Bimal Roy twinkled amongst stars.

Baba's Bombay debut, Maa, starred the Bombay Talkies star Leela Chitnis with a host of unknowns like Shyama, Bharat Bhushan, Nazir Hussain. It was a Hindi adaptation of a Hollywood sentimental Over the Hills by William Fox. The loneliness of the elderly, the neglect they suffer and their dependence on the young was the main theme. Baba was preparing to pack his bags when Ashok Kumar signed him to make Saratchandra's Parineeta under his banner. The making of Parineeta and the First International Film Festival held in Bombay dramatically changed our destiny. It opened new vistas for the entire Bimal Roy team.

Do Bigha Zamin took the world by storm. Remember it was the first Indian film to secure a theatrical release at the Metro reserved only for overseas films. Arguably, Do Bigha Zamin is inspired by De Sica's Bicycle Thieves. The film ushered in neo-realism. But the story Baba made was written by Salil Chowdhury. Ritwik Ghatak had taken Baba to see a new Bengali film, Rickshawala, by director Satyen Bose written by Salil Chowdhury. The story appealed to Baba. On 14 August 1952, the day Salil Chowdhury was getting married, he received a telegram asking him to meet Bimal Roy in Bombay. An incident Mrs Jyoti Chowdhury recalls fondly even today. What happened after that is history.

Baba shot Do Bigha Zamin by night and Parineeta by day. He had the responsibility of the welfare of several families as his technicians had moved to Bombay. He was aware that his productions house had to bring prestige and succeed at the box office. Not all were to turn to box-office gold like Parineeta. In an industry where the success rate is 5 per cent, debacles wait to happen. The film Baap Beti, produced by a fly-by-night operator, Munshiji, was one such. He could not pay the technicians. In a rare burst of anger, Baba ordered his assistants to pick up the furniture from the sets of Baap Beti and furnish their homes.

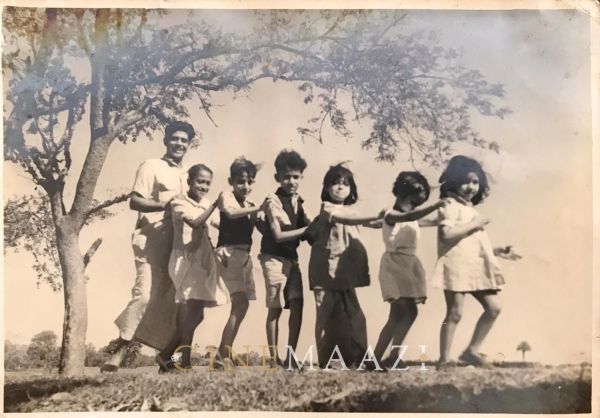

Looking back, our childhood appears enchanted, filled with radiance. One way to describe Baba would be as a contented householder. His concern for the family took priority. Fame, success never clouded his vision. On weekends, he took us to swim in Anderson's pool. By evening, we headed for treats to the Outram Ghat Café serving Calcutta's best chicken sandwich. He would plan my birthday a month ahead. We accompanied our parents to the finest cultural events – watched Uday Shankar dance with the ravishing Madam Simki, saw the Bolshoi Ballet performing Swan Lake, heard Ustad Ali Akbar's divine sarod. Thanks to him, we were exposed to the best. Family trips to the enchanting Nilgiris, to Darjeeling. Perhaps we were too young to savour the exquisite art of great artists or even appreciate the places we visited. But these images and sounds absorbed at an impressionable age enriched our life. The one thing I have lived to regret bitterly was rejecting Baba's generous offer to study at Oxford. In 1959, he took me on a trip to see colleges in Oxford. Being an adamant teenager, I had turned down this brilliant prospect.

My father's cinema was never the obvious boy-meets-girl-romance variety – they are layered with social legitimacy. What inspired him about maestros like Sergei Eisenstein, De Sica, Tagore, Chaplin – his kindred souls across the globe – was their profound regard for humanism and human dignity. And in turn, he inspired the younger generation of film-makers, Ray, Ghatak, Mrinal Sen, Tapan Sinha, Jahnu Barua, Ashutosh Gowarikar. This established my father as a pioneer par excellence. In his own words, in his jury address in Moscow, 1959 he concluded:, 'Cinema is an asset to promote understanding among people of different cultures. In our generation the world has grown smaller with distance conquered by technology, cinema is the most important medium to help man understand his responsibilities and potentials, to identify new areas of activity to enjoy the beauty of new relations amongst various people – for there exists an universal kinship.'

In a brief lifetime accorded to a human being, my father, Bimal Roy, was able to transform the profile of Indian cinema and touch the collective consciousness with his celluloid parables. He was a sage of cinema. One of his great admirers once told me, he is to cinema what Tagore was to literature. He truly was.

This feature is a modified and expanded version of an essay appearing in Bimal Roy: The Man Who Spoke in Pictures published by Penguin Group, 2009.

The original essay did not feature any of the images.

None of the information and/or images in the feature may be reprinted/replicated without the author's permission.

Tags

About the Author

Ms Rinki Roy Bhattacharya is a published author of Penguin/Random house, HarperCollins, and SAGE India, besides being a veteran journalist and documentary film maker. She has been a freelance journalist for reputed publications like Times of India and Indian Express. She has been the recipient of several prestigious scholarships including research fellowships & honorary doctorates. She has been invited on prestigious International and domestic Jurylike the Mumbai International Film Festival and Amsterdam Documentary Festival.. An acknowledged specialist on women and film studies, she is frequently invited to take master classes at reputed educational Institutions like Berkley, SOAS,TISS, NFAI, SNDT ,Sophia college amongst other places. She has been the Vice Chairperson of the Children's Film Society of India. She has been the recipient of multiple honours from the School of Oriental and African Studies in the U.K., TISS, Rotary Club and the Bangladesh government. She has co-directed the doucmentary Char Diwari and the short film Janani. She has edited multiple publications like Behind Closed Doors/Domestic Violence in India, Janani: Mothers, Daughters, Motherhood and Bimal Roy: The Man Who Spoke in Pictures and authored Bimal Roy, A Man of Silence, Bimal Roy's Madhumati: Tales From Behind The Scenes and Bengal Spices.

.jpg)