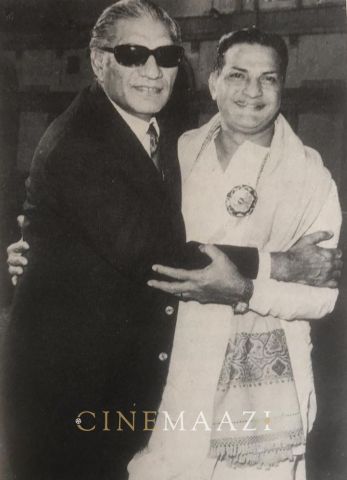

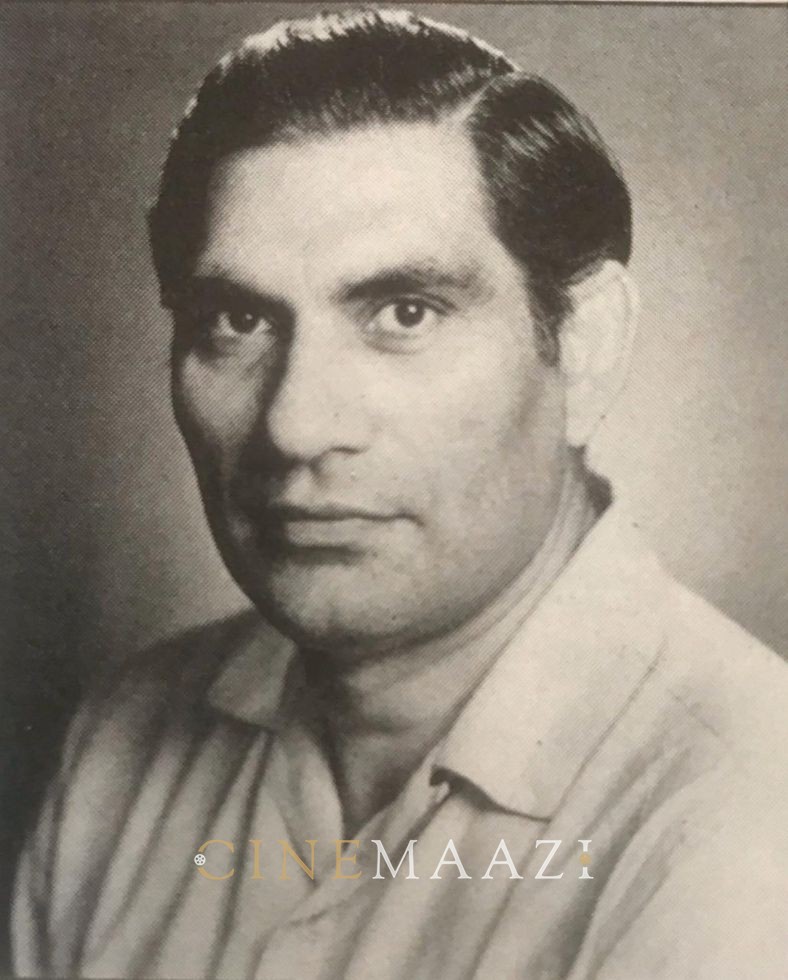

Journalist-turned producer-director B.R. CHOPRA, who has made several socially relevant movies, writes on the sorry state of producers in India today.

You really don’t have to search for an answer for the question posed. It is so obvious. In one sentence. We are not united and perhaps will never be.

You will now want to know the reason. That also is quite obvious and you don’t have to search far for it.

There is an-built weakness in the production sector because of its overall dependence upon everything and everybody else, particularly the temperamental and unpredictable human element, which goes into the making of movies.

An army of indisciplined soldiers cannot make for victory. The worst part is that the indiscipline seems part of the producer’s physiognomy. He cannot think freely. The very set-up around him makes him a slave, not a master. You will say, ‘But, sir, even slaves fight for freedom?’ No, it appears that after the struggle for independence, we have lost the zest for any further battle. And you will find this attitude of mental inertia in all walks of Indian life.

I do not know how united we were before Partition but I do know that there were no serious problems affecting the industry. We had only a dozen or so producers and each one of them turned out half a dozen or more movies. There was no star-system-at least in had not assumed the pernicious proportions it has today. By and large, artistes were attached to individual producers and worked on a permanent basis. And whenever an artiste appeared in the movie of another producer, he was loaned by courtesy of his/her studio.

Production in those days did not involve the hassles there are today. Punctuality and discipline were taken for granted and truancy was only exceptional. I remember how once Mazhar Khan, a busy star of yesteryear, arrived late on the set of Prabhat’s ‘Padosi’. Director V. Shantaram shouted, “Pack-up” and folded up for the day to teach the artiste a lesson, and to show him that coming on time was not a matter of choice, however big the artiste - it had to be respected as a routine.

The Brand that Counts

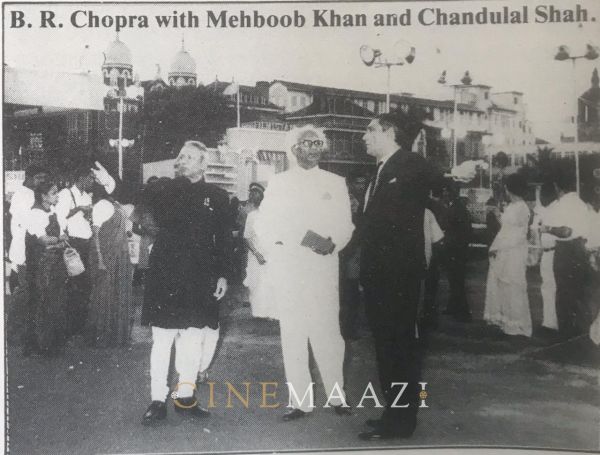

The producers and directors held a place of prestige and we seldom heard about a confrontation on the sets. I will not forget the incident when a popular director was called from Calcutta by Ranjit chief, Chandulal Shah; the director stated his price as one rupee higher than the highest-paid artiste. Those were the days when the directors were respected and the film’s quality was determined not so much by the star names as by the name of the brand.

On the business side also the relationship between the various branches was based largely on a mutual recognition of business ethics. By and large the production concerns had permanent distribution outlets and rarely did we hear about any internecine skirmishes. In fact, except for IMPPA, which was there to regulate production problems, if any, and which was there to regulate productions problems, if any, and which was there simply to announce annually the leader of the industry (which did to some extent import politics into the ranks of producers), there were no other associations. Perhaps there was no need for these, as both in the production and the distribution sectors, there was a sense of mutual respect and business was run according to traditionally accepted ethics. The long association of producers and distributors can be traced in practically all the institutions of those times ranging from Wadias to Prabhat and from New Theatres to Ranjit. It was only a rare C.M. Trivedi who, unable to fit into the pattern of things, struggled to introduce free-lancing in the ranks of directors and artistes. But and large, however, peaceful co-existence reigned between the various sections of the industry.

Even the exhibitor, who has a stranglehold monopoly today, had not discovered the middle-man at that time; it was a matter of personal pride to him to show good films to his clients. He was not merely a profit-making machine as he is today. He was deeply interested in the product he showed and just as the producers made pictures and provided the products, the exhibitor held himself responsible for the money and ploughed back earning into films thus completing the cycle of business. The producer distributor relationship was that of a manufacture-trade and often becomes a closely-knit unit. In some cases, even the exhibitor joined this unit when he acknowledges a preference for a particular brand or a couple of brands. Nishat, Lahore, for example carried the emblems of Ranjit, Bombay Talkies and New Theatres in the lobby and showed the pictures of these three brands on the basis of absolute priority.

The Government in those days had very little to do with films. Censorship was no problems and entertainment tax appeared only in the mid-forties-and that too only as a token levy. They did not have a Morarjee to think of an excise duty on prints because, in those days, the British rulers did not like to tax entertainment. It was left to free Indian to invent taxes on entertainment possibly because free Indian society has no right to free entertainment (according to some unmentioned mandate of Mahatma Gandhi).

Before and After

This then is the picture of the Indian film industry prior to independence and Partition. Organizational set ups had some kind of an in-built financial base which protected the producers against the vagaries of box-office and since they were harassed by the Government or a hostile Censor, they were able to devote time (which these days is consumed in wooing the Government) to improve the quality of their pictures. Most of these set-ups have left their mark in the history of the industry. Whether they were united or not really did not matter - they seemed to run their business comfortably, and the technicians and artistes seemed to work harmoniously together. We did not hear of two-hour shifts or stars absconding from sets.

Then artistes did not like to work in too many movies. Work in the studios progressed in an orderly fashion and there was no congestion in any department. People enjoyed working and they did not have to unite against any outside agency or any tendencies which created indiscipline. When I came to Bombay as a journalist in the year 1938, I found the film industry was just one big family. I repeated my visits almost every year and always this happy family atmosphere greeted me. There was a sense of healthy rivalry, which worked in the interest of quality. And even in the case of artistes who were the “selling points” in those days too there was a friendly give and take between them. Indiscipline was not tolerated by anybody and the producer was both respected and feared.

But after the War and the advent of free-lancing, the scene changed drastically.

During the war years, there was shortage of raw stock and rationing was introduced. There were, however, certain adventurers who managed to get hold of raw stock and made their unwelcome appearances as producers. For the first time in the history of Indian motion pictures, we saw the emergence of the so-called independent producers who had no studios nor any organization to back them up, and who, in a short while, brought about or encouraged free-lancing for the first time in the industry.

This movement of the independents gained momentum when the Partitioned ripped the country into two and gods of refugees crossed over from the North in search of livelihood. Some of those refugees spilled over into Bombay and some settled for a career in films. I was one of those refugees who had no qualification excepts the will to fight starvation. For the refugee producer on organizational set-up was not possible. Nor had they the resources of the old production concerns.

That the organizations did fade out under the pressure of the independents is true. The independents too have become victims in their own time. The Indian producers is accused of selling himself to the box-office and as such is an anti-social monster. He must make way for the new wave so that art may again find its place in the industry.

During the days of the organizations, quality was the main concern of the producers because they believed that a good picture was a good proposition. But now a good proposition comes before the picture. The main concern is to make the money before the release of picture. The emphasis on selling stars has made the producer a mere broker. And since we depend upon stars they are beyond our control. This has resulted in multi-assignments and gross indiscipline. The producer is rendered helpless and that’s why he needs to unite for strength. But, as I said, inherent weakness and lack of disciplined approach stand in the way.

United Front

In the year 1952 (or was it earlier?), the industry made the first attempt to regulate itself and present a United Front. A hug meeting of IMPPA was held at Taj. Stalwarts like Chandulal Shah, J. B. H. Wadia, Rai Bahadur Chunilal, Mehboob and Karder along with other important independents like Kishore Sahu, Jaimani Dewan, and other smaller fry like me too, attended the stormy meeting. A passionate piea was made for solidarity, “United we stand, divided we fall” - the saying was cheered by the distinguished assembly. As a first step, it was decided that there must be a ceiling or curb on the assignments of stars, for it was the only way a producer could come into his own make quality movies. it was unanimously decided that the ceiling would be fixed at two films. Applause. Signatures in blood. High hopes. That was the first meeting of the industry I had attended. And I was very happy to see the veterans taking such an enthusiastic stand. And in the right direction. But before the ink or shall I say the blood on the paper had dried, fissiparous tendencies made themselves apparent. The first positive step taken by the industry to bring about unity and sanity in the profession was nipped in the bud.

Some of the producers rebelled against the resolutions with the result that the stars stayed in their seats of power and the producer vacated his. From then on to this day the process of deterioration has been steady. While star assignments have sky-rocketed, the shifts of shooting have shrunk from eight hours to 80 minutes (it is 60 minutes but I am allowing 20 minutes for removing make up and leaving one shooting for another).

In the year 1951, the Government of India appointed a Film Enquiry Committee headed by the late S. K. Patil. Their findings were welcome by the industry but unfortunately the report proved an exercise in futility. Because, against all the recommendations of its own committee, the Government went ahead and burdened this industry with all kinds of taxation. Today, the film industry is the most highly taxed industry in the world. Why the Government has chosen to punish this industry with such back-breaking taxation is difficult to understand.

When we put this question to politicians and ministers, they have a ready answer, “You makes bad pictures”. With a view to teaching us how to make good picture, the Government of India set up a financing wing (FFC, and now NFDC) to promote talent and quality pictures. How far they have succeeded in their mission is something on which I won’t comment.

Perhaps the Government feels that the only way to improve the quality of films is to load producers with taxation, so that they will either die or leave the profession, making way for those chosen by the Government to make the movies at its expense. Since the Government refuses to listen, I will refrain from telling that too much of taxation has always resulted in deterioration of quality of both humans and materials.

When Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru was the Prime Minister of India, he wrote all his Chief Minister to see that the sweepers were provided larger size brooms so that they didn’t have bend while sweeping. This would not only increase efficiency, it would also promote the dignity of human. How I wish we had another Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru to write to Chief Ministers to say that burdening people does not improve their efficiency and even film producers are human beings.

Neither can the Indian producer turn to his Association for help.

The Association, after all. Derives its strength from individual members. The film industry, in main, is peopled by one- movie producers, who have to struggle for existence. His main interest is in the welfare of his own picture and to protect it against all odds, he loads it with all kinds of box-office ingredients, which he hopes, will fetch him finance and distributors. Now this man, whose own existence depends upon others, is too weak to implement any decision of his Association. And most producers belong to this one picture category. Perhaps the producer wants unity but unity calls for personal sacrifice.

Let us examine why we need unity:

Well, first of all, we need it to stand against the Government which has been crippling the industry with wanton and mindless taxation.

But you will, perhaps, say that in this the industry has always spoken with one voice - against the entertainment tax and excise levy and against unnecessary curbs on raw film. You are right. There has been a united stand in his sphere. We have been speaking with one voice - but the Government has not heeded that. Possibly because the Government knows that this is not the unity of strength. And the unity of weakness is ineffective.

Seconds, we need unity to regulate and discipline our working in and out of the studios. Here we have tried and failed. It is just not possible to have collective thinking.

It is really a shame - but undoubtedly a fact - that we have not been able to implement any resolution of our Association. Self-regulation and discipline are the crying needs of our industry, but these call unity which we do not have or we are not able to have.

This is a reproduction of the original published in Fifty Years Of Indian Talkies (1931-81).

.jpg)