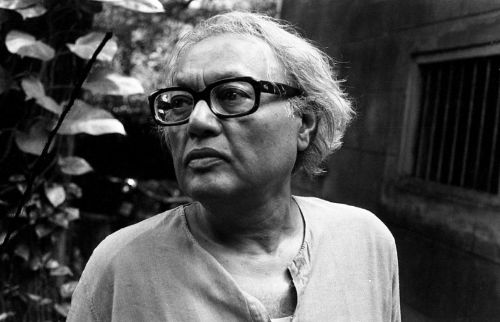

Subrata Mitra

Subscribe to read full article

This section is for paid subscribers only. Our subscription is only $37/- for one full year.

You get unlimited access to all paid section and features on the website with this subscription.

Not ready for a full subscription?

You can access this article for $2 , and have it saved to your account for one year.

- Born: 12/10/1930 (Calcutta)

- Died: 07/12/2001 (Kolkata)

- Primary Cinema: Bengali

- Parents: Shanti Mitra, Shudhangshu Bhushan Mitra

One of the most renowned and influential cinematographers of the twentieth century, Subrata Mitra left an indelible mark on the progression of Indian cinema’s aesthetics. Known primarily for his ground-breaking work on Satyajit Ray’s Apu Trilogy, Mitra was also a mentor figure for many young filmmakers and cinematographers who followed in his footsteps.

He was born on October 12, 1930 in Calcutta to Shanti and Shudhangshu Bhushan Mitra. His father worked in the India Equitable Insurance Company, dabbled in scientific research and was arguable one of the first Indians to earn an M.B. degree from London. Subrata Mitra passes his matriculation from Ballygunge Government High School (the same school Satyajit Ray studied in) and later obtained an I.Sc. from St. Xavier’s College. By this time, he was quite interested in cinematography. He was disillusioned with the prevailing cinematographic practices of Indian cinema and Hollywood, but admired the work of James Wong Howe, Boris Kauffman, Guy Green and Robert Burkes. He was also influenced by the naturalism of Henri Cartier-Bresson’s photography. He started looking for opportunities for an apprenticeship with an established cinematographer, but his prospects looked bleak. In his despair, a ray of light pierced through in the form of Jean Renoir’s visit to Calcutta.

Renoir’s visit to shoot The River proved influential on many counts – one of which was that it brought Satyajt Ray and Subrata Mitra together for the first time. Renoir encouraged Mitra in his pursuit of becoming a cinematographer and also let him join his crew as a production assistant. Ray, who used to visit the sets of the film looking for similar inspiration from Renoir, met Mitra and made his desire to make a film known to him. Mitra’s contribution to The River was not only as an assistant though. Being a trained sitar player, he played the film’s title theme. Some of his photographs were also used by the film’s production company as publicity material.

Ray originally wanted the veteran Nemai Ghosh (of Chinnamul fame) to do the cinematography of Pather Panchali. But when Ghosh had to back out due to his commitments down south, Ray asked Mitra to take up the baton. Although Mitra by that time had mastered still photography, he had never worked with a movie camera before. Nervous at undertaking such a monumental project with little to no experience, Mitra nevertheless agreed. He later said in an interview to Filmfare, “I still do not know who was more reckless – Mr. Ray in making the offer or I in accepting it.”

Pather Panchali had to be shot in bits between 1951 and 1954, due to severe financial constraints. But Ray and his committed crew persevered, in the process altering the course of Indian cinema forever. Needless to say, the film was a monumental success, widely regarded as the most significant Indian film of the twentieth century. Mitra’s outdoor camerawork with the Arriflex, brought a genuine neo-realist flavour to the film’s aesthetics. It also dispelled many pre-conceived prejudices against outdoor shooting and the use of natural light. But the innovation that Mitra is known for – ‘bounce lighting’ – came during the shooting of the second part of the trilogy Aparajito (1956).

Ray initially wanted an outdoors set for the shooting, but the possibility of the onset of monsoons convinced the art director Bansi Chandragupta to move the set to a studio. Fully aware that the diffused effect of natural light is impossible to recreate with direct artificial lights, Mitra came up with a solution. He stretched layers of white cloth on the ceiling, trained his lights on them and shot the film in the reflected light. This technique came to be known as ‘bounce lighting’. Years later, Sven Nykvist, the cinematographer for Ingmar Bergman claimed to have invented the technique. But by that time the technique was already common knowledge in Indian cinema, thanks to Mitra’s ingenuity.

The Ray-Mitra partnership gave many more unforgettable classics over the next few decades – Paras Pathar (1958), Apur Sansar (1959), Devi (1960), Kanchenjungha (1962), Charulata (1964) and Nayak (1966). He enjoyed the challenge of shifting to colour in Kanchenjungha, approaching it with the same intrepid determination as he had done in Pather Panchali. Astonishingly the film only consumed 29 rolls of colour negative whereas an average Hindi film would take up to 350 rolls. Among the other Ray films, both Charulata and Nayak remain all-time great achievements in composition of mise-en-scene.

Mitra was also influential to the early works of Merchant-Ivory. At the time of shooting for his first film The Householder (1963), James Ivory had little experience in making a feature film. It was Mitra’s guidance which helped him through the process. He shot most of the film with six photoflood lamps. He shot the Merchant-Ivory film The Guru (1969) entirely with halogen lamps, making it a first for Indian cinema. He also dabbled in Hindi cinema occasionally. He was the cinematographer for Basu Bhattacharya’s underrated classic Teesri Kasam (1966) and Ramesh Sharma’s taut political thriller New Delhi Times (1985).

The man responsible for transforming the way we see cinema dealt with eye-related problems his whole life. He had a damaged left eye from a tennis injury in childhood. During the filming of Devi (1960), the retina of his right eye came detached. But even such handicaps could not stop him from returning to the camera. He married in 1958 and his wife was a schoolteacher. In 1997 he became Professor Emeritus of Cinematography at the Satyajit Ray Film and Television Institute in Kolkata. He won the 1986 National Film Award for Best Cinematography for New Delhi Times. He was awarded with the Padma Shri by the Government of India in 1986. He passed away on 7 December, 2001 in Kolkata.

Speaking of a meeting with Mitra, Dev Benegal once said, “‘What is the language of light?’ he asked me once. Looking at my blank face he answered, ‘It’s music.’” Indian cinema would be forever enriched by the musical notes of light Subrata Mitra had gifted.

References

Image Courtesy: upperstall.com

.jpg)