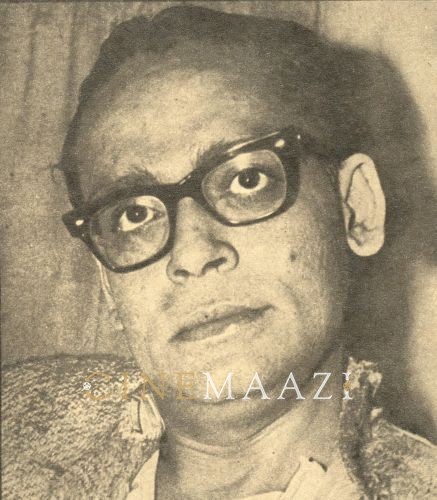

Ritwik Ghatak

Subscribe to read full article

This section is for paid subscribers only. Our subscription is only $37/- for one full year.

You get unlimited access to all paid section and features on the website with this subscription.

Not ready for a full subscription?

You can access this article for $2 , and have it saved to your account for one year.

- Born: 04/11/1925 (Dhaka, British India)

- Died: 06/02/1976 (Calcutta, West Bengal)

- Primary Cinema: Bengali

- Spouse: Surama Ghatak

- Children: Samhita Ghatak, Ritaban Ghatak,Suchismita Ghatak

A cornerstone of the Bengali cultural psyche, and arguably the most important Indian filmmaker of the twentieth century, Ritwik Ghatak’s story is often told as that of the tragic genius. His brilliance was always accompanied by erratic behaviour, a perennial restlessness and alcoholism, which resulted in his relatively sparse output over his two-and-a half decade-long film career. To be fair, it is as easy to paint Ghatak as the wastrel genius, as a story of what-could-have-been, as it is infinitely difficult to fathom the power of the few films he left behind which have become timeless classics.

Born on 4 November, 1925 in Dhaka, he migrated to Calcutta with his family at a young age. His father was a magistrate and his brother Manish was a poet. Witnessing the horror of the Partition and the famine of 1943, Ghatak carried its trauma with him all his life. He became politically active in Calcutta, and joined the Indian People’s Theatre Association in 1948. He wrote his first play Kalo Sayar the same year and also participated in a performance of Bijon Bhattacharya’s seminal play Nabanna. He subsequently wrote plays like Jwala (1950) and Officer (1952). He formed the Natyachakra Theatre Group, before joining Shombhu Mitra’s Bohurupee group. He was voted the best theatre actor and director at an all-India IPTA conference held in Bombay in 1953. But soon ideological differences led to his departure both from the IPTA (1954) and the Communist Party of India (1955). He set up his own theatre troupe in 1954 inspired by Stanislavski’s methods.

His foray into cinema began with an assistant director’s position in Manoj Bhattaacharya’s Tathapi(1950). He acted in Nemai Ghosh’s landmark Chinnamul (1951) and followed it up with his own directorial debut in Nagarik (1952). The film remains his most explicitly political film, detailing the struggles of a North Calcutta family with poverty and their gradual political awakening. The film is marked by Ghatak’s signature use of the wide-angle lens and the tensions between melodrama and realism that characterised his films. The film was unable to find a release during his lifetime and only saw the light of day in 1977.

In 1955, he shifted to Bombay taking up the job of a scenarist for Filmistan Studios. Ghatak struggled to adjust in the city, with his experimental filmmaking sensibilities clashing with the more commercial demands of the producer Sashadhar Mukherjee. Still, Ghatak left his mark in Hindi cinema, writing the story for Bimal Roy’s superhit Madhumati(1958). He was also credited as a scriptwriter for Hrishikesh Mukherjee’s directorial debut Musafir (1957). He made several documentaries in the meantime like Adivasiyon Ka Jeevan Srot (1955).

His return to Calcutta sparked off the most sustained period of creative output of his life. Films like Ajantrik (1957), Bari Theke Paliye (1958), Meghe Dhaka Tara (1960), Komal Gandhar(1961) and Subarnarekha (1962) were produced during this time. Ajantrik, Meghe Dhaka Tara and Subarnarekha are widely counted as among the greatest films ever made. A striking aspect of these films was his attention to the folk traditions of rural Bengal, introducing a never-before-seen idiom in Bengali cinema. Despite being rooted in the local, his films made broader political statements about the refugee condition of the world, critiquing the cultural fragmentation suffered through the Partition. Despite being a committed Marxist, he would deviate from the mandated social realist form to utilise melodramatic tropes, that gave his films a particularly forceful emotional charge. One of the first filmmakers to directly address the Partition in post-Independence cinema, Ghatak’s films would investigate the many layers of social upheaval that ensued from it. These films also represented his experimentation with the epic form. The Partition trilogy (Meghe Dhaka Tara, Komal Gandhar and Subarnarekha) contain his most stringent critiques of the failures of the Indian state in addressing those who were marginalised by the cataclysmic event. Komal Gandhar, based around a musical troupe, was also semi-autobiographical in nature.

During this time, he also scripted films like Swaralipi (1961), Kumari Mon (1962), Der Nam Tiya Rangwip (1962), and Raj Kanya (1965). He was invited to be a guest lecturer at the Film and Television Institute of India. He was later appointed as the institute’s director in 1966. Despite the unpredictability of his actions, he cut a charismatic figure. He exerted a tremendous influence on his students at the FTII, withl, Mani Kaul, John Abraham and Kumar Shahani later emerging as his most famous pupils. Even an out and out commercial filmmaker like Subhash Ghai was deeply affected by his teachings. Filmmakers like Saeed Akhtar Mirza were inspired by his presence to challenge the commercial style of the industry. He would famously hold his lectures under the Wisdom Tree on the campus, often inebriated, yet holding his audience captive. His stint in the institute was over by 1967, as abruptly as it had begun. Ghatak was both elated in his role as teacher, but also felt ill-at-ease and claustrophobic as revealed in letters written to his wife Surama.

He continued making documentaries and writing screenplays during this time. He wrote the screenplay for Heerer Prajapati (1968) and directed the short film Amar Lenin (1970). His struggles with alcoholism were catching up with him though, even leading him to spend time at a mental asylum. Even incarcerated, he wrote the play Sei Meye and performed it with his inmates at the asylum. He directed the short film Durbargati Padma for the Films Division in 1971. His next fiction feature, Titas Ekti Nadir Naam (1973), based in the Malo fishing community along the Titas river, masterfully captured the dread of inevitable industrialisation. It was made in collaboration with a Bangladeshi producer, reportedly inspired by the sight of the river Padma witnessed from a plane by Ghatak and was based on a novel by Adwaita Mallabarman. For many this film was his masterpiece, using mythical allusions to open up the history of the class divisions of Bengal. His last film Jukti Takko Aar Gappo (1974) famously starred himself as the acerbic intellectual Neelkantha in his most cynical film. Ghatak passed away on 6 February, 1976, before his last film could find its official release. He left behind an unfinished documentary on the sculptor Ramkinkar Baij which was later finished by his son Ritaban. In 2013, he was the subject of a biopic, which borrowed its name from his most famous film, Meghe Dhaka Tara.

Ghatak was uncompromising and confrontational, never satisfied within any institutional framework, inevitably finding them to be dogmatic. He was deeply committed to the art of political cinema, yet never wanted to make propaganda as was mandated by the Party. A keen student of history and mythology, his films often explored the entangled caste and class relationships that shaped Bengali society, never making for easy viewing. Barring Meghe Dhaka Tara, none of his films touched commercial success, yet his name is universally known in Bengal today, his films only increasing in relevance with time. Perhaps Ghatak’s life can be best encapsulated by the last words uttered by Neeta, his protagonist from Meghe Dhaka Tara – ‘Ami bachte chai’. I wish to live – the indomitable desire to live beyond all frontiers.

References:

https://www.nybooks.com/daily/2020/01/25/a-new-look-at-ritwik-ghataks-bengal/

Encyclopaedia of Indian Cinema. Ed. Ashish Rajadhyaksha and Paul Willemen. New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1998.

-

Filmography (9)

SortRole

-

Subarnarekha 1965

-

Suvarna Rekha 1962

-

Komal Gandhar 1961

-

Meghe Dhaka Tara 1960

-

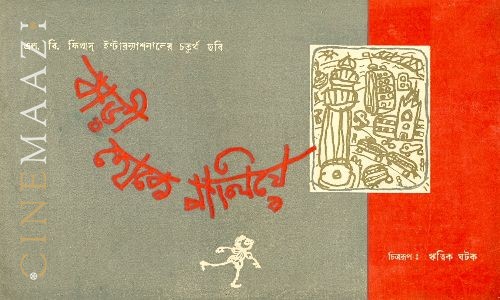

Bari Theke Paliye 1959

-

Ajantrik 1958

-

Nagarik 1952

-

Awards (1)

National Film Awards, 1974

Best Story: Jukti Takko Aar Gappo (1974)

.jpg)