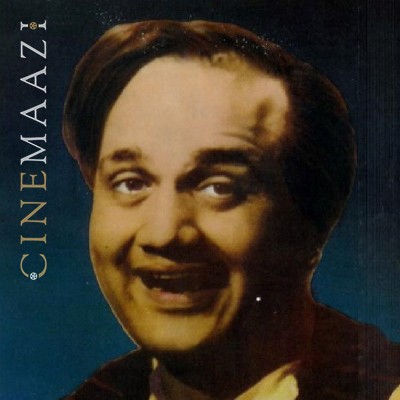

Peter Pereira

Subscribe to read full article

This section is for paid subscribers only. Our subscription is only $37/- for one full year.

You get unlimited access to all paid section and features on the website with this subscription.

Not ready for a full subscription?

You can access this article for $2 , and have it saved to your account for one year.

- Born: 1929

- Died: 10 January 2023

- Primary Cinema: Hindi

Veteran cinematographer and special effects expert, Peter Pereira has been described as “a figure at the cusp of the transition from old-fashioned mechanical illusions to the computer-generated special effects that define 21st-century cinematic spectacle.” (Scroll.in). Memorable for achieving the invisibility of ‘Mr India’ in the eponymous film of 1987, he worked on more than 30 films over five decades in the cinematography and special effects departments, including other fantasy films like Sheshnaag (1990) and Ajooba (1991), as well as multiple genre films such as Mahabharat (1965), Amar Akbar Anthony (1977), Yaarana (1981), Desh Premee (1982), Coolie (1983), Shahenshah (1988), Aaj Ka Arjun (1990), Dil Aashna Hai (1992), Lal Baadshah (1999), Vadh (2002), and Bhagmati (2005). In an interview, Pereira would later explain, “Obviously, the camera captures only natural things. Special effects are meant to create phenomena that exceed the natural.” He also appeared onscreen in a scene in Amar Akbar Anthony.

Born in Uttan in 1929, he grew up in Vasai, to the North of Bombay, where his parents’ house still exists. In 1970, he would move to an apartment in Juhu, where he would live permanently. His father worked in film distribution with MB Billimoria, a leading figure in the Bombay film industry of the 1940s, who was also a contemporary and collaborator of the well-known producer Homi Wadia, and would commute to Grant Road for his work. Despite growing up with a father who worked in the film business, he did not visit film sets regularly. When the time came for him to find employment, he joined the Homi Wadia-owned Basant Studio in Chembur. Here, he worked as an apprentice, doing odd jobs, setting up cameras and handling other menial tasks.

His interest in photography was sparked by his father, who was a photography enthusiast. He shared his father’s hobby and enjoyed photography from the very beginning, throughout his youth. He used the small Brownie camera he owned to take lots of pictures. During his time as an apprentice at Basant Studio, being in the whole environment in which films were being made, he also became attracted to motion pictures.

He worked with pioneering special effects specialist Babubhai Mistry, who was a trick photographer at Basant Studios. As Homi Wadia used to produce many mythological films, considerable trick photography was required for the unusual, fantastical scenes. As his assistant, Pereira learned a lot from the highly innovative Mistry.

Incidentally, in the 1930s and 1940s, since his father was a film distributor, his job was to take the film to the theatre, wait till the run was over and then get the tin back. He would accompany his father on these trips. While he enjoyed watching comedy films and specifically Charlie Chaplin, it was the Douglas Fairbanks film called The Corsican Brothers (1941), in which he played a double role, that inspired Pereira to make films.

Working with Basant Studios, which was known for producing mythological films which feature events that cannot occur in reality, he worked with the team on scenes which required trick photography, such as to show Hanuman flying. To achieve this, the make-up artist provided Hanuman with the mouth and tail, and then wires would be used to portray the flying. Working to create effects in times before computers, he employed unique techniques. For example, in his first film Parasmani (1960), the camera passes through a tunnel in which there is huge, 20-feet-long lizard. The lizard was crafted with rubber. In order to make its eyes open and close so that it looked more realistic, a smaller rubber lizard was used and plastic doll’s eyes inserted, which were controlled using a fine thread.

Shedding light on the Mistry film in which Hanuman had to fly, the actor was made to lie on his stomach atop poles that were painted black so that they couldn’t be seen. He would support himself on the poles and pretend to fly. It was shot against a white background to enable a cut-out of the scene. The sequence of cut-outs created the look like he was flying in the sky. In order to give the feeling of unsteadiness, clouds were superimposed onto the shot to create the effect of motion.

Pereira produced perhaps his most memorable work with Mr India, for which he achieved the ‘invisibility’ of the eponymous lead character. He would reveal in an interview, “Mr India was a totally different concept to what I had done before. This was about an invisible man. But we used traditional mechanical tricks, so it was actually all shot before the camera, unlike the digital post-production interventions used today. For example, the scene in which Mr India goes near Mogambo’s feet and picks up a bracelet: we tied the bracelet to a very fine black thread and pulled the thread out of frame so that it appears as though Mr India, the invisible man, was doing so.”

He shared that fine wires were tied behind objects and actors, which were used to make it look as though they were floating or being controlled by some unseen force. For instance, in a scene where a little boy is being twirled around by Mr India, a boom was used to balance him and hang the wires through which he could be moved in and out.

Pereira also used many in-camera tricks, explaining that “the disappearance/appearance shots were dissolves managed by the camera – basically you superimpose consecutive shots of the actor moving to make it look like he is vanishing and reappearing. For a shot in which the boy sees Mr India’s face and neck in red glass but the rest of his body was missing, we used the classic masking technique. We shot Mr India normally, with the lower half covered with black paper, and then again using a red filter on the lens. Then we combined the two separate images to create one image.”

For the scene in which Mr India leaves footprints on the mud and then on the floor, he used a stop motion technique in which one footprint after another was made as static images and then shot one frame at a time. When the frames are played in sequence, it appears as if an invisible person’s shoes are leaving footprints.

Calling it a “beautiful film,” he recalls his experience of working on Mr India as an easy, straight-forward experience, with director Shekhar Kapur telling him what he wanted, and he accomplishing it. He worked on the film on a per day basis. On the set, he didn’t work closely with the cinematography department, headed by cinematographer Baba Azmi, unless he wanted something changed. Apparently, for one scene in which he took one shot, Azmi came up and asked whether he was sure about the lighting. In response, Pereira asked him to bring him an egg and he would light it in 25 different ways! Interestingly, he never thought the film would become the mammoth hit it did.

The film “remains a classic for its special effects, a rare stab at science fiction in mainstream Hindi cinema.”

For the scene in Sheshnaag, which depicts the transformation between the snake and the woman, a dissolve was used. As he explains, analog cameras have an optical printer to perform a dissolve by turning a handle. An object is lit, the shutter is closed, and the second object, which it has transformed into, is lit when it is reopened.

In his opinion, the most fun effect he achieved in his career was for a Homi Wadia film titled Shri Ganesh Mahima (1950). It involved replacing the head of a child with an elephant’s, which is Ganesha’s story. Placing the camera at the bottom, he put the body of a four-year-old child with a black mask on his face. Then he exposed the child to the camera. Without moving the camera, he placed a plastic tusk above his body and removed his mask, and then exposed it again. The third time, he exposed him was when the child was getting up. Using these multiple exposures, he achieved a naturalistic look, as though the boy just grew a trunk. He also a small close-up of Parvati looking at him, thus achieving the effect of maintaining continuity.

Pereira also had the chance to go to Hollywood many years ago, where he met great cinematographers like Jack Cardiff, who was known for his work with Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger, and James Wong Howe, who was among the earliest cinematographers to use deep focus.

Speaking about the transition from practical effects to CGI, he reveals that it was time-consuming to do everything through physical processes, and eventually, when it started becoming possible, the effects business was transferred to laboratories, with Film Centre in Tardeo, Mumbai, being one of the first labs to make computer graphic-based effects. He admits that while many special effects artists understood the new technical aspect, many older people who didn’t have knowledge of computers and digital technologies left the line. Some even became editors, possibly due to the craft demanding a similar understanding of optical effects. Labs, in turn, went out of business with the coming of digital technology in the 1990s.

Enjoying a long and fruitful career, working from the 1960s through the new millennium, Pereira passed away on 10 January 2023. He was 93 and had lost his eyesight to glaucoma for more than 20 years. Sharing the news of Pereira’s demise, actor Abhishek Bachchan wrote in a tweet, “Our industry lost a legend today. #PeterPereira was a pioneer in cinematography in our films. One of the greatest!” He also added, “I remember him fondly from the sets of my father’s films that I visited as a child. Kind, loving, dignified and brilliant. Rest in peace, sir.”

Shekhar Kapur recalled Pereira as “a gentle genius. Patient. Always innovative. Constantly coming up with solutions,” adding, “Mr India still stands tall as a spectacular visual effects film. And that too from long before we had sophisticated digital visual effects. Remember the scene where the kid and Mr India first discover the invisibility bracelet? That scene required three passes of the film negative in the same frame! It was the most patient and careful work I’ve ever seen on camera.”

Pereira was last seen in filmmaker Hemant Chaturvedi's documentary, Chhayaankan, which profiled 14 cinematographers who worked in Hindi films between the 1950s and the 2000s. He was featured alongside Govind Nihalani, Jehangir Chowdhury, Pravin Bhatt, Kamalakar Rao, Ishwar Bidri, S M Anwar, Baba Azmi, A K Bir, Nadeem Khan, Barun Mukherjee, Dilip Dutta, RM Rao and Sunil Sharma. Chaturvedi acknowledged his passing on social media, writing, “The legend is no more. A career of over 60 years. Peter Pereira passed away today. Cinematographer & Special Effects genius. He went blind 20+ years ago and was conveniently forgotten by his fraternity, in the typically callous and selfish way in which our film industry functions. Other than his presence in my documentary film, there exists only one other interview of the man who spawned several generations of excellence. He is the star of my documentary and his effect on my life cannot be explained. It’s a sad reflection of the Bombay film industry and its abject selfishness and arrogance that is continuously appalling and grotesque. I wish Peter Uncle eternity and immortality. There will never be another one like him.”

.jpg)