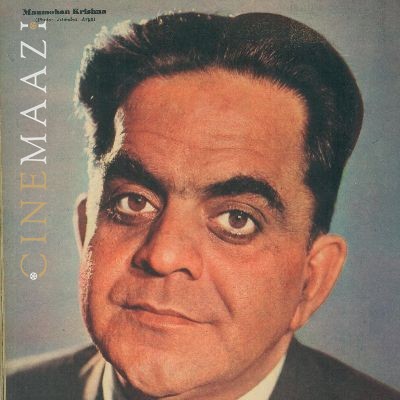

Mrinal Sen

Subscribe to read full article

This section is for paid subscribers only. Our subscription is only $37/- for one full year.

You get unlimited access to all paid section and features on the website with this subscription.

Not ready for a full subscription?

You can access this article for $2 , and have it saved to your account for one year.

- Born: 14/05/1923 (Faridpur, British India)

- Died: 30/12/2018 (Kolkata)

- Primary Cinema: Bengali

- Spouse: Gita Sen

Lending new meaning to politically committed filmmaking, Mrinal Sen was one of the filmmakers who ushered in the Indian New Wave. One of India’s most decorated and internationally renowned filmmakers, Sen primarily worked in Bengali cinema, but also dabbled in Hindi, Telugu and Oriya films. Sen’s Bhuvan Shome (1969) brought about a seismic shift in the Indian film landscape, often regarded as the starting point of the parallel cinema movement. Moving away from the naturalism and humanism that characterised filmmakers like Satyajit Ray, Sen’s cinema drew upon a range of influences – from Latin American Third Cinema to the works of European filmmakers like Francois Truffaut and Federico Fellini (alongside non-film influences like Augusto Boal’s Theatre of the Oppressed). Sen had described his intention was to shock the audience out of the conventions of mainstream cinema, which he found to be conformist.

Born on May 14, 1923 in the town of Faridpur (now in Bangladesh), Sen came to Calcutta after finishing high school to study physics. He was involved with the cultural wing of the Communist Party of India as a student. He was a member of the IPTA from 1943 to 1947. He later credited this atmosphere as shaping his political consciousness. At that time, he was not interested in cinema at all. After finishing his college in 1942, he became interested in sound recording and one day just walked into a studio and was hired in its maintenance department. Relegated to working with capacitors and condensers, Sen quickly grew weary of the job. He decided to study on his own to learn more about sound recording.

While conducting his studies at the Imperial Library, he came upon the book Film as Art by Rudolf Arnheim (the same book sparked off another New Wave stalwart Mani Kaul’s interest too). Realising that there is more to cinema than he thought, he started consuming whatever books on cinema he could find. He also started watching Russian films at the Friends of the Soviet Union organisation. He published his first essay, Film and The People at the organisation’s journal. His writings initiated debates among leftist intellectuals about the potential of cinema. He also attended screenings organised by the Calcutta Film Society.

Just after Independence, the political atmosphere turned turbulent with the Communist Party being banned. It was during this time he started toying with the idea of making a film and even wrote his first script. Unfortunately, the film did not pan out so he continued writing prolifically, including a book on Chaplin and translating the novel The Cheat by Karl Capek. In 1956, in an atmosphere which was encouraging to alternative filmmakers after the success of Satyajit Ray’s Pather Panchali, he found a producer for his first film. He made his debut with Raat Bhore (1956), but later distanced himself from it, calling it a disaster. Feeling discouraged, he was almost convinced to give up filmmaking when in 1959 he got the opportunity to make another film. Neel Akasher Nichey (1959) produced by the legendary composer Hemanta Mukherjee (Hemant Kumar) was a commercial success. Telling the story of an immigrant Chinese hawker in Calcutta, it attempted to link India’s freedom struggle with anti-imperialist struggles worldwide. The film also contained one of Mukherjee’s most famous compositions – O majhi re ekti kotha sudhai tomare. It also included documentary footage shot in China, a feature Sen would expand upon later in his career. But in the wake of the Sino-Indian war the film was banned, bizarrely after three years of its release. Although this film too later drew criticism from Sen himself, it went a long way in establishing him in the industry.

He felt differently about his third film Baishey Shravan (1960) based on the devastating effects of the famine of 1943 on a married couple’s lives. The film again ran into trouble with the censors, due to its title referring to Rabindranath Tagore’s death day despite having no apparent connection to it. Sen stood his ground and had the title approved. He wrote Ajoy Kar’s Kanch Kata Hirey (1966) and Ajit Lahiri’s Joradighir Choudhury Paribar (1966). and he continued making films namely Punascha (1961), Abasheshe (1963), Pratinidhi (1964); the French New Wave inspired Akash Kusum (1965) which sparked off a famous newspaper debate between Satyajit Ray and Sen over the effectiveness of such filmmaking; Matira Manisha (1966) which was his only Oriya film based on Kalindi Charan Panigrahi’s famous novel starring future Oriya stars Sarat Pujari and Prashanta Nanda; and a couple of short films for the Films Division until his major career breakthrough, Bhuvan Shome.

Made on a flimsy budget provided by the Film Finance Council, Sen’s satirical film about a bureaucrat’s encounter with a village girl (played by Utpal Duttand Suhasini Mulayrespectively) was a commercial success. Its unconventional editing and narrative structure would have a huge influence on future independent filmmakers. It also led to a change in the policy of the FFC which earlier would only grant money to those who could provide a guarantor. His Calcutta trilogy (Interview, 1970; Calcutta ’71, 1972; Padatik, 1973), set against the backdrop of the Naxalbari uprising and violent suppression of the student movements, became a political event of sorts. The films’ screenings were regularly raided by police as they became meeting places for leftist activists. The documentary footage of mass protests in Calcutta used in the films became an interesting intersection of public and private memory, as students spotted their friends and colleagues in them who had since ‘disappeared’ during the purge against student politics. In between he made Ek Adhuri Kahani (1971) which was based on the same Subodh Ghosh novel that inspired Bimal Roy’s Anjangarh (1948) and Sujata (1959).

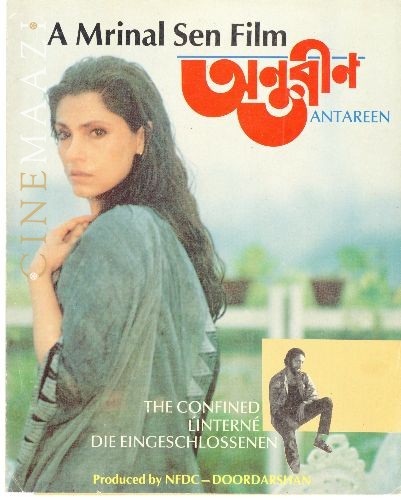

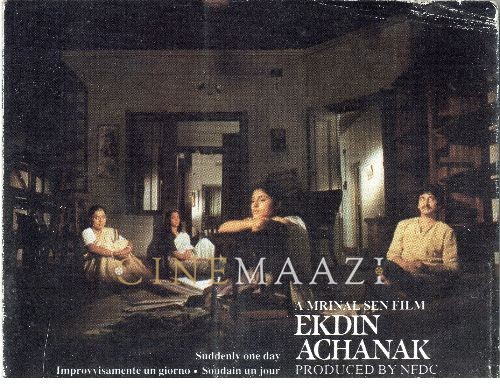

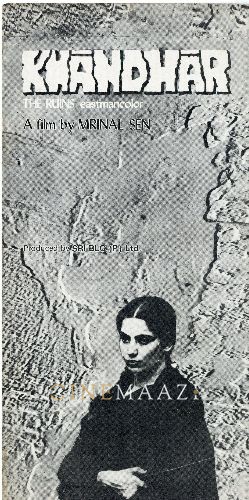

Playing upon the mythological form and mixing it with realism and avant garde techniques, Chorus (1974) presented Sen at the height of his experimental style. His next film, the allegorical tale of Mrigaya (1976) was a more restrained but focused effort, portraying the story of an adivasi who cruelly comes to realise the true nature of colonialism. Oka Oorie Katha (1978), a Telugu film, based on Munshi Premchand’s Kafan, was a bitter tale of poverty and patriarchal exploitation. Ek Din Pratidin (1979), made in the style of a thriller, began his exploration of middle-class life. Akaler Sandhaney (1980) returned to the setting of the famine of 1943 and shifted between two timeframes – 1943 and 1980. It won great acclaim, winning multiple National Awards. He followed it up with the comedy Chaalchitra (1981); the much darker portrayal of middle-class apathy inKharij (1982); the Robert Bresson inspired Khandhar (1983); a television film made for Doordarshan Tasveer Apni Apni (1984); the allegorical tale Genesis (1986); and the semi-autobiographical Ek Din Achanak (1988). His activity decreased in the 90s when he made only two feature films – Mahaprithibi (1991) and Antareen (1993). His last feature film was Amar Bhuvan (2002). After his book Chaplin, he also authored four more books – Views on Cinema (1977), Cinema, Adhunikata (1995), Montage (2002) and Always Being Born (2004). He also made 14 short films and five documentaries.

Sen remains one of the most decorated filmmakers of India, winning 18 National Awards and major honours at prestigious film festivals like Moscow, Karlovy Vary, Berlin, Cannes, Venice, Montreal and Cairo. He was awarded the Padma Bhushan in 1981, the Ordre des Arts et des Lettres in 1985, and the Dadashaheb Phalke Award in 2005. He was also a nominated Rajya Sabha MP from 1997 to 2003. The veteran filmmaker passed away on 30 December, 2018 at his Bhowanipore residence in Kolkata, leaving behind a most varied and unique body of work in Indian cinema.

References

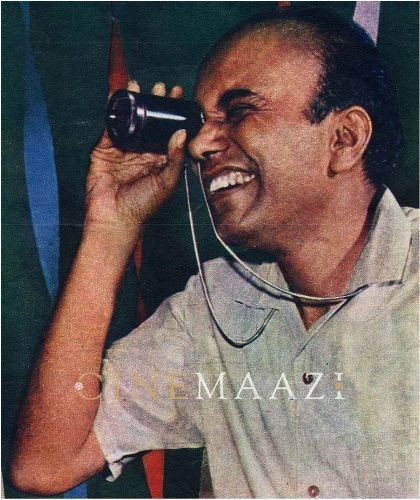

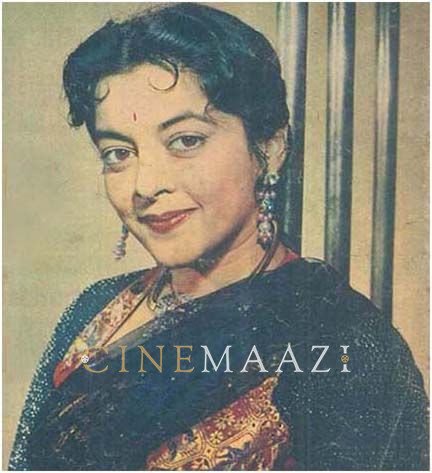

Image courtesy: mrinalsen.org

-

Filmography (32)

SortRole

-

Aamar Bhuban 2002

-

Amar Bhuvan 2002

-

Antareen 1993

-

Mahaprithivi 1991

-

Ek Din Achanak 1989

-

Genesis 1986

-

Khandhar 1984

-

Khandahar 1983

-

Kharij 1982

-

Chalchitra 1981

-

Akaler Shandhaney 1980

-

Ek Din Pratidin 1979

-

.jpg)