Dharam Veer Ram

Subscribe to read full article

This section is for paid subscribers only. Our subscription is only $37/- for one full year.

You get unlimited access to all paid section and features on the website with this subscription.

Not ready for a full subscription?

You can access this article for $2 , and have it saved to your account for one year.

- Real Name: Dharamveer Ram; Jerry Ram

- Primary Cinema: Hindi

Jerry Ram, better known by his original name Dharam Veer Ram, started as an extra and graduated to scriptwriting in the late 70s. Jerry was the name given to him by the Irish nurses at the hospital where he was born in Karachi. After Partition, the family moved to Nagpur where Jerry studied at the Bishop Cotton School. Always fond of dancing and being spectacularly good at it at a young age, Jerry never got the formal training he deserved. His father never liked the idea of Jerry becoming a dancer.

However, he continued to dance, his father’s objections notwithstanding. As a student of medicine in Delhi, he joined a cultural group and performed at various events. His dancing got him attention from the public and the seeds of the desire to pursue stardom had taken root. Abandoning his studies, 17-year-old Jerry moved to Bombay to achieve his dreams. Unable to find work, he returned to his home in Nagpur. However, he found living with his father challenging and chose to return to Bombay. He ended up doing odd jobs as a record-changer in Astoria Hotel, or as a store-keeper in a hardware shop opposite Central Studio.

One day he came across an advertisement that took Jerry to Delhi to meet Richard Maitland, who had come down from the USA to form a dance group. Jerry was happy to be recognized as a professional dancer for the first time. After training with Maitland for a while, Jerry got a job in the Premiere Hotel in Jammu. It was here that Jerry caught the attention of film producer Brij Katyal, who had come location hunting for Burma Road (1962). He offered Jerry a small role together with Mohan Choti.

After that, Dev Anand gave him a role in Tere Ghar Ke Samne (1963). Later he teamed up with Sharon to form a touring cabaret group called Jerry and Sherry. He also continued being part of the faceless chorus in films like Gul-e-Bakawali (1963), Ek Din Ka Badshah (1964), and Sangam (1964). In the latter, he danced with Tina Katkar, mother of actress Kimi Katkar, in the song Har dil jo pyar karega wo gaana gayega with the camera pulling away from their faces.

Even after these stints in films, 24-year-old Jerry was not happy as the future seemed hazy, and work in films was not always regular. Slowly his dreams seemed to be dissolving. At this stage, his father advised him to join his brother in Hong Kong in his export-import business. Jerry grabbed the offer and moved to Hong Kong. However, when Jerry enrolled himself in the Carol Bateman School of Dancing in Hong Kong, much to the disappointment of his family, he was again thrown out on the streets.

This time Jerry survived by dancing for the Indian community at Hotel Hilton. After a year of this, he had collected enough money to apply to the Rambert School of Ballet in London.

With £100 in his pocket and a renewed hope in his heart, Jerry landed in London. However, he soon learned that the school was expensive. To pay his fees he washed dishes from 6 pm to 1 am. This took a toll on his health and he had, again, no choice but to leave the school. As he struggled in the city, he joined a drama school and through the Oriental Casting Agency, he succeeded in getting the role of “the boy” in Zia Mohyeddin and Madhur Jaffrey’s The Guide in New York. But as luck would have it, the play didn’t do well and a heart-broken Jerry returned to London. For the next two years, he managed to get work on television, typecast as an Indian, always projected in a derogatory manner. He even had to put on a foul accent which he didn’t have. Tired of playing the bumbling Indian, Jerry found his way back to India in 1970. Unable to adjust to a life of an extra, he kept knocking on the doors of producers to get small roles in films, but only faced disappointment.

He did small roles in films like Bhoola Bhatka (1975), Kasme Vaade (1978), several of Basu Bhattacharya’s films, and Harjaee (1981). It was the latter that broke his heart. Jerry, who was 40 by now and still being treated worse than an extra, decided to give up acting. While he was experiencing a phase of mental turmoil, Jerry was asked to write a script by another Indian from London, Avtaar Bhogal for his film Videsh (1977). Jerry had helped him earlier with parts of Ek Hans Ka Joda (1975), in which he had also acted. Videsh, starring Mahendra Sandhu and Shoma Anand, was shot entirely in London. The film never got released but it did help Jerry to find a new career.

All his anger, frustration, and years of struggle found an outlet in screenwriting. He used his real name Dharam Veer Ram and as a screenwriter, wrote the screenplay for films like Cobra (1980), Manav Hatya (Madhuri Dixit’s first film, unreleased), Aaj Ke Angaarey (1988), Raat Ke Andhere Mein (1987), Gentleman (1989), Trinetra (1991), Sailaab (1990), Vishkanya (1991), Sainik (1993), Andhera (1994) and Dance Party (1995).

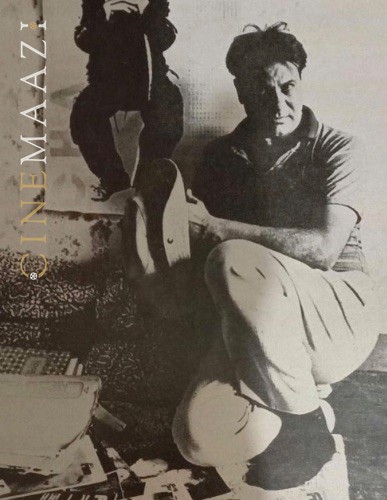

Interview of Dharam Veer Ram published in a magazine, June 10, 1990

Why does anyone opt to be a face in a crowd? A face that cannot be identified. And, yet is. As an extra. What makes these faceless entities hang around an entire lifetime on the periphery of a world that is callously unaware of their existence?

Hope. Perhaps? Hope that one day the camera will zoom in on their face instead of sweeping past it. Mumtaz and Mithun Chakraborty, too after all started out as nobodies in a crowd, didn’t they? Inspired by such tales, the film industry’s lesser children are happy being part of the background of painted props and cardboard cut-outs. With the majority of them have run away from their homes to become stars in tinsel town, they have little choice, anyway. Fear of ridicule prevents them from returning to their roots as mere mortals and failure. So they pull along in an industry that has condescendingly agreed to recognize them as ‘junior artistes’ but, in effect, continues to treat them as extras.

The story of Jerry Ram is the story of one such extra. However, this story has a slight twist. Today, Jerry is no longer an extra. He has graduated from an extra to scriptwriting and is now known by his original name, Dharamveer Ram.

Jerry was the nickname given to him by the Irish nurses at the hospital where he was born in Karachi. After Partition, the family moved to Nagpur where he studied at the Bishops Cotton School. His earliest memories of this age are those of his aunts sitting around on charpais, coaxing him to dance. ‘Dance, Jerry, dance!’ They would say and the little boy would promptly oblige with a perfect rendering of a Cuckoo number. Only to be later beaten up black and blue by a disapproving father.

“If my father had encouraged me to do what I had a natural aptitude for, I might have been a Gopi Krishna today. Had I received formal training at that age I would have had the world at my feet,” says Jerry bitterly in an interview, never having forgiven his father for having failed to understand him.

But Jerry continued to dance, his father’s objections notwithstanding. As a student of medicine in Delhi, he became a member of a cultural group. To cries of ‘Encore’, Jerry twirled and twisted, enjoying every moment of his new-found glory. “I discovered dancing got me attention,” he recalls. The seeds of a desire for stardom had taken root. Much to the chagrin of the senior Ram, an army man.

Finally, unable to tolerate his son’s penchant for doing the ramba-samba any more he gave Jerry an ultimatum- ‘Go to Bombay if dance you must’, So, abandoning his studies, the 17 years old Jerry packed his bags and arrived in the city of glitz.

But, like thousands before him, this star-aspirant discovered Bombay was not just glamour. Walking the mean streets of the demanding city, for the first time, Jerry realized life was no song. Unable to get a job even as an office-boy, the young lad returned to his father’s home. “But, three months of claustrophobia with him made me return to Bombay. The hardships of this city were preferable to the comforts of my father’s house.

This time he was luckier. Doing odd jobs, a record-changer in Astoria hotel as a store-keeper in a hardware shop opposite Central Studios where his heart lay, Jerry was able to survive. Then one day, an advertisement in the Papers had him taking the train to Delhi to meet Richard Maitland who had come down from the USA to form a dance troupe.

“I met him at the Ashoka hotel. He thought I had the potential! For the first time, I was being recognized as a professional dancer! I began to feel clean and good once again,” Remembers Jerry, his face glowing even now as he speaks of that event. “I also had my first brush with homosexuality, but I wouldn’t say I found the experience unpleasant. I remember he smelt very good. Yes, I too had to sleep for a role,” says Jerry candidly.

After training with Maitland for a while Jerry got a job in Premiere hotel in Jammu. By a strange quirk of fate, his father happened to be posted there at the same time and the manager of the hotel got a special thrill introducing his lead cabaret dancer as Colonel Ram’s son to a clientele that comprised mainly uniform men.

It was here that Jerry caught the attention of film producer Brij Katyal who had come location hunting for Burma Road. He offered Jerry a role of a sidekick together with Mohan Chhoti. Thus he managed to put his foot into the film industry.

After that Dev Anand gave him a role in Tere Ghar Ke Samne. “At lunch break one day,” relates Jerry, “I requested the film director, Vijay Anand, to let me dance for them. He let me do so, and I danced, putting everything into my performance. Not realizing that nobody was impressed or interested.”

According to Jerry. “In India being a dancer means being an extra. You are not a human being-just part of a herd of cattle-humiliated by all and sundry. You have to keep quiet and swallow all the indignities heaped on you as your very survival depends on these rude, heartless men.”

Unable to create a ripple what the disappointed youth did do was team up with Sharon. As the Jerry and Sherry team, they toured the country doing cabaret numbers at hotels. He also continued being part of the faceless chorus in the film like Gule Bakawali, Ek Din Ka Badshah and Sangam. In the latter, he danced with Tina Katkar - Kimi Katkar’s mother-and the songs Jo ek din pyar karega who gaana Gayega started with the camera pulling away from their faces. A great moment for any chorus dancer.

But apart from such consolations, there was little to make the runaway feel happy with his choice of profession. “In India being a dancer means being an extra. You are not a human being - just part of a herd of cattle - humiliated by all and sundry. Even the suppliers don’t talk to you decently. You have to keep quiet and swallow all the indignities heaped on you as your very survival depends on these crude, heartless men, he reveals.

Twenty-four-years-old Jerry had no option. The future was a blur, living as he did from one working shift to another, his dreams totally shattered. At this stage his father came into his life once again, advising him to join his brother in Hong Kong in his import-export business. Shrewder as he had become by now, Jerry looked upon Hong Kong as a passport to America. He grabbed the offer.

But when he got himself enrolled at the Carol Bakeman School of Dancing in Hong Kong his family was predictably outraged and once again Jerry found himself out in the street. This time, Jerry survived by dancing for the Indian community at Hotel Hilton. After a year of this, he had collected enough money to apply to the Rambert School of Ballet in London.

With £100 in his pocket and renewed hope in his heart, Jerry landed in London. However, he soon learned that bullet was an expensive preoccupation. So after classes, he washed dishes from 6 pm to 1 am. But daily dishwashing played havoc on his muscles. “You either be a waiter or dancer.” Warned the doctor. And Jerry chose to be a waiter. For that brought him £5 a night as tips. For the first, he had money to splurge. “I even began behaving like an Englishman, visiting pubs, etc,” says Jerry with an Ironical tinge of pride.

After that, he joined a drama school and through the Oriental Casting Agency, he succeeded in getting the role of ‘the boy’ in Zia Moihuddi and Madhur Jaffrey’s The Guide in New York. “For the first time, I got a script in hand!” But, as luck would have it, the play didn’t do well. Totally dejected, his hopes of becoming another Babu shattered, Jerry returned to London. With the words of a co-star ringing in his ears. “Don’t pray for success. Pray for work.”

The next two years, in fact, did see him getting a lot of work, mainly on television. “But, I began to feel like the scum of the earth, type caste as an Indian always projected in a derogatory manner. They never showed Indians well-dressed or articulate. I represented my country in the worst light. I even had to put on a foul accent which I didn’t have.” Explains a man who cannot take humiliation for long.

Tired of playing the bumbling Indian, Jerry returned to India in 1970. To start all over again, knocking at producer’s doors for two-minute roles. What followed were years of agony. He was a total misfit, unable to adjust to the life of an extra. “I was unhappy about being merely part of the background. I couldn’t identify with my peer group. Nor could I suck up to the heroes and live off the benefits of being part of star cutlery,” says Jerry, shuddering even now when he thinks of his life then.

But for 11 long years, the middle-aged dancer persisted, doing the two-bit roles in films like Bhoola Bhatka, Kasme Vaade (“you’d need a magnifying glass to spot me in this one”). Several of Basu Bhattacharya’s films and Harjaae. It was the last film that really broke his heart. “I was 40 years old and still being treated worse than an extra. That’s when I decided I couldn’t continue trying to be an actor. If becoming an actor meant so much of humiliation, then I didn’t want to be one.

“For six months after my decision, I experienced acute mental torture. I had cut off links with my family. I had tried my luck in the West, I couldn’t take Bombay on its terms - I just didn’t know what to do. I had touched the rock bottom of my existence.”

It was at this time that another Indian from London, Avtaar Bhogal, asked him to script his film, Videsh, Jerry had helped him earlier with parts of Ek Hans ka Joda in which he had also acted. Videsh was shot entirely in London.

The film never got released. But it served to help Jerry change tracks. All his years of struggle, his pent-up emotions of found an outlet. In scriptwriting. Videsh was followed by Manav Hatya (Madhuri Dixit’s film, also unreleased). Some more films followed. But none of them did well. “I am a working writer today but I have yet to taste success,” states the writer of Trinetra (a Mithun starrer). Sailaab (with Madhuri Dixit as the leading lady), Vishkanya, and several others, frankly. What keeps him going is what has kept him going for 50 years-hope. “Maybe one of these films will do well and I’ll finally be accorded my valid place in this industry,” he says wistfully, trying not to sound too pessimistic.

Looking back upon it all, how does he feel? “So many of us have left our homes thinking we well get artistic satisfaction working in films,” he points out. “Only to discover that this work is no different from other professions. Film-making is a business like any other and to succeed here you have to be hard and unscrupulous.”

But in all these decades if there is a man for whom he has undiluted praise it is Raj Kapoor. “He was lavish in every sense. A true film-maker, it was Raj Kapoor who put us on the world map. He was the only genuine film-maker I have worked with, the only human being who treated all other human beings as equals.”

And finally, any advice for the numerous strugglers, the other Jerrys of the industry? “I would say that if you don’t have a fierce ambition to make it as a star, go back. Or else you will be reduced to playing a shadow all your life. It’s all right for those from poor families who are not qualified to be anything else, to work as daily wage laborers. But if you have an alternative there is no reason to stick around here like living corpses.”

- contributed by Mr. Sudarshan Talwar

-

Filmography (1)

SortRole

-

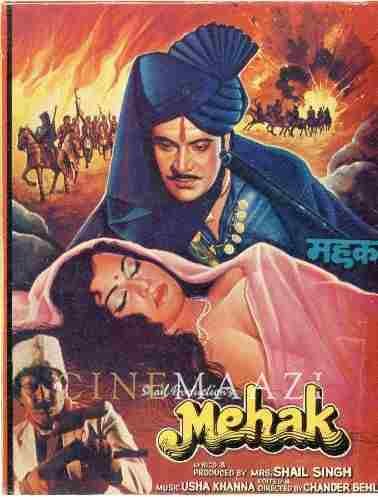

Mehak 1985

-

.jpg)