Baburao Patel

Subscribe to read full article

This section is for paid subscribers only. Our subscription is only $37/- for one full year.

You get unlimited access to all paid section and features on the website with this subscription.

Not ready for a full subscription?

You can access this article for $2 , and have it saved to your account for one year.

- Real Name: Baba Patil

- Born: 4 March, 1904 (Maswan, Maharashtra, India)

- Died: 4 September, 1982 (Bombay, Maharashtra, India)

- Primary Cinema: Hindi

- Parents: Jamuna and Pandurang Vithal Patil

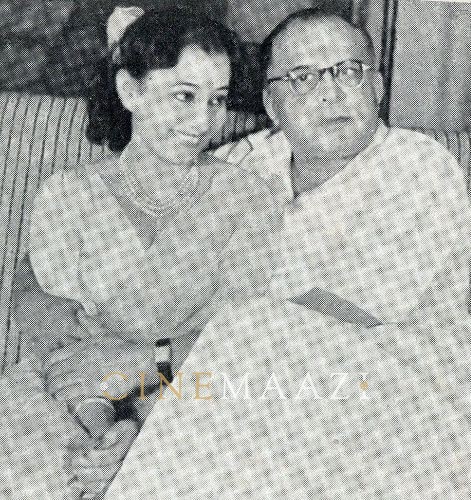

- Spouse: Shirin, Sushila Rani (nee Tombat)

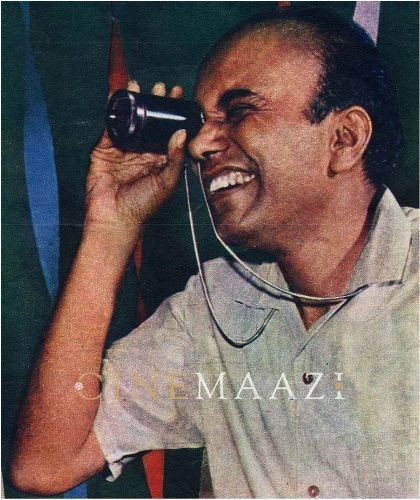

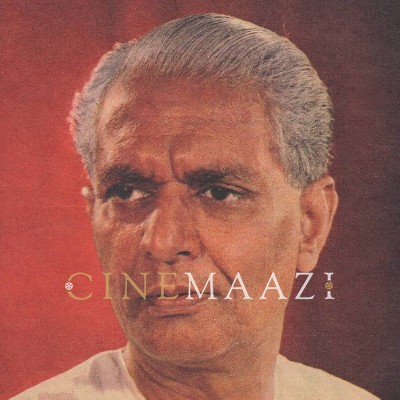

Film director and producer Baburao Patel is better known for being a pioneering film journalist, and co-founder-editor of the monthly magazine Filmindia, the most influential film magazine through the 1940s and 1950s, and which continued to be in publication right till the 1980s. Touted to be the most feared journalist in the Indian film industry, his comments in his columns, film reviews and popular Q and A section were widely followed by his fans. Its popularity spread far beyond Indian borders, finding subscribers even in distant places like Fiji and Africa. Known to receive thousands of letters from readers across the world, the connect he shared with his public was as strong as it was rare. No less a personage than Sadat Hassan Manto would say of him, “Baburao wrote with eloquence and power. He had a sharp and inimitable sense of humour, often barbed. There was a tough guy assertiveness about his writing. He could also be venomous in a way that no other writer of English in India has ever been able to match.” In 1960, with his magazine diverting from cinema commentary to politics, he rebranded it as Mother India. Even after his demise in 1982, his wife, Sushila Rani continued to publish the magazine until 1985, its 50th anniversary—apparently, the couple had decided on this before he died. Venturing into politics, he was elected to the Lok Sabha as the Jana Sangh candidate from Shajapur, Madhya Pradesh in 1967. His film directorials include the silent film Kismet (1932), Sati Mahananda (1933), Maharani (1934), Bala Joban (1934), Pardesi Saiyan (1935), Draupadi (1944), Gwalan (1946), and Matwali Meera (1947). He is also credited with producing Gwalan.

Born on 4 April, 1904 in the village of Maswan, around 100 kilometres from erstwhile Bombay, his father, Pandurang Vithal Patil, was one of the few lawyers from the Vanzara community in the village. Incidentally, the family name – Patil changed to Patel over the years, leading many to mistakenly believe that he was a Gujarati. The demise of his mother Jamuna, when he was just four years of age, saw him being brought up by his uncle and father, who had remarried. When the family moved to Bombay, he was admitted to St. Xavier’s school; however, he struggled with studies and quit school without completing his matriculation. Incidentally, this lack of formal education was to be a source of bother to him in later years. While he held intellectuals and scholars in high esteem, he also worked simultaneously on soaking in knowledge on a range of subjects, from Hindu philosophy and international politics to alternative medicine.

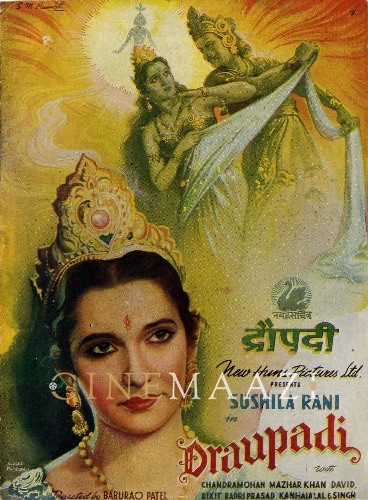

In order to earn a living, he took up various odd-jobs including peddling inexpensive miracle cures. His tryst with journalism started in 1926, when he joined Cinema Samachar, a new film magazine, which is believed to have been published in Hindi, English and Urdu. Gradually, he entered the burgeoning field of cinema, evolving as a scriptwriter and director. He made his directorial debut with the silent film Kismet (1932). It was followed by the Mubarak-starrer Sati Mahananda (1933), the action-drama Maharani (1934) starring Padmadevi, Raja Pandit, and Shirin Banu; and Gandharva Cine’s Bala Joban (1934) which featured Gulab, Shirin Banu, and Madhukar Gupta. His other directorials include Pardesi Saiyan (1935) with a star cast that comprised Azoorie, Shirin Banu, and Mubarak; Draupadi (1944) written by and starring Sushila Rani, Chandra Mohan, and Mazhar Khan; and Gwalan (1946) starring Trilok Kapoor, Madhuri, and Sushila Rani. His directorial Matwali Meera (1947) starred Mukhtar Begum, Nissar, and Ranjit Kumar.

His association with journalism endured—in 1935, along with the owner of New Jack Printing Press – D N Parker, he started the film magazine Filmindia. Launched as a monthly in April that year, it was printed on high-quality art paper. The cover flaunted a hand-painted image of actress and novelist Nalini Tarkhud, whose V Shantaram directed film Chandrasena (1935), was advertised within. The content included art plates of the stars of the time and film stills of latest releases.

As editor, he pointedly stated his desire “of supporting this industry by honest journalism and constructive criticism of men and things and aspire to create a taste in our readers for Indian pictures (that) are representative of Indian culture and traditions.” He also claimed to wish to uphold and promote Indian culture.

His blunt and brazen style of reviewing ruffled many feathers, yet he continued evidently without fear of offending advertisers, declaring that they were welcome to stop their ads if they wished. One brutal verdict of a film he reviewed went thus – ‘Most wretched, boring and amateurish hotch-potch’. In another instance, he likened the story of Ranjit Movietone’s Desh Dasi (1935) to “an old pair of trousers made serviceable by bright and coloured patches,” adding that the direction by Chandulal Shah had “certainly degenerated. An artiste at one time, in his hunt for money he has left his ideals far behind and in Desh Dasi we find him as the superintendent of the Mint rather than as a director.” In this, he had the support of his co-publisher Parker, who stood by him when Shah’s brother Dayarambhai informed them that no more ads would be forthcoming! In the review of the film Fashionable India (1935), he bluntly declared that one of the actresses - Johra Jan, had “no face, figure or voice”! He also didn’t hesitate to call Kalpana Kartik “pigeon chested”, Suraiya “ugly”, Dev Anand “effeminate”, and referred to Meena Kumari’s shape as an “inverted shuttlecock”.

His column ‘Bombay Calling’, under the pseudonym Judas, saw him lay bare the shenanigans of the film industry in an entertaining fashion. Commenting on the influx of Bengali filmmakers, he pointed out, “All these Bengalees have committed a great mistake in coming down to Bombay and create [sic] a new graft of culture in our industry. I do not think they have been received well and in fact some of them have been grossly insulted.” In blunt fashion, he castigated fighting stars, in-name-only film production companies, and dubious producers who tried to get over-familiar with heroines. Incidentally, Shiv Sena supremo Bal Thackeray was one of the cartoonists who contributed to Filmindia at Rs.10 per cartoon!

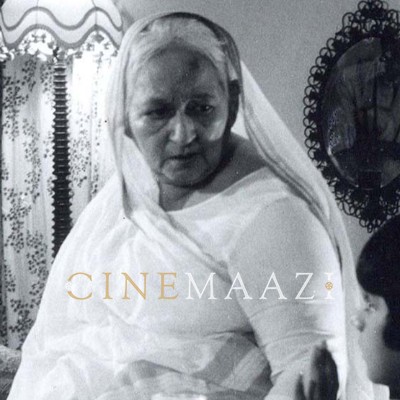

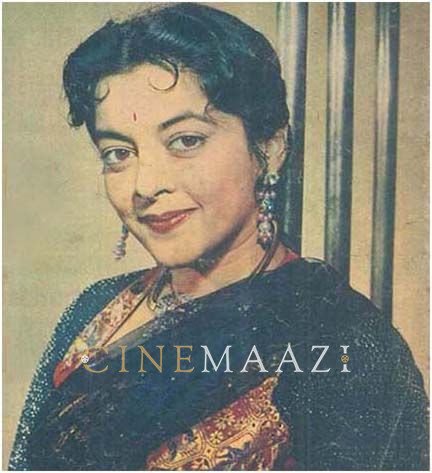

Interestingly, though Filmindia was a huge success, money was not exactly flowing his way. Apparently, he became the first person in his family in 500 years to go bankrupt! He thus, on the side, also accepted assignments to pen ad copy for films. He did, however, enjoy the good life along with ex-actress wife, Sushila Rani, who also worked alongside him in Filmindia. Apparently his third wife, he had initially directed her in a few films. Together, they made an extraordinary couple who were ‘loved, respected and feared by the film industry in equal measure’. Sidharth Bhatia’s well-produced book, The Patels of Filmindia: Pioneers of Indian Journalism, gives an insightful account of the movie magazine run by the couple for 50 years.

The books he has to his credit include The Rosary and the Lamp (1966), Burning Words: A Critical History of Nine Years of Nehru's Rule from 1947 to 1956 (1956), Grey Dust (1949), and A Blueprint of Our Defence (1962).

Baburao Patel passed away on 4 September 4, 1982 in Bombay.

References

Sources: https://scroll.in/article/733935/most-wretched-boring-and-amateurish-hotch-potch-meet-baburao-patel-pioneering-film-journalist

https://www.thequint.com/entertainment/meet-the-most-feared-journalist-in-the-film-industry#read-more

https://theprint.in/features/filmindia-baburao-patels-irreverent-magazine-that-could-make-or-break-a-movie/403749/

-

Filmography (4)

SortRole

-

Gwalan 1948

-

Draupadi 1944

-

Bala Joban 1934

-

Kismet 1931

-

.jpg)