Winds of Change- Marathi Cinema

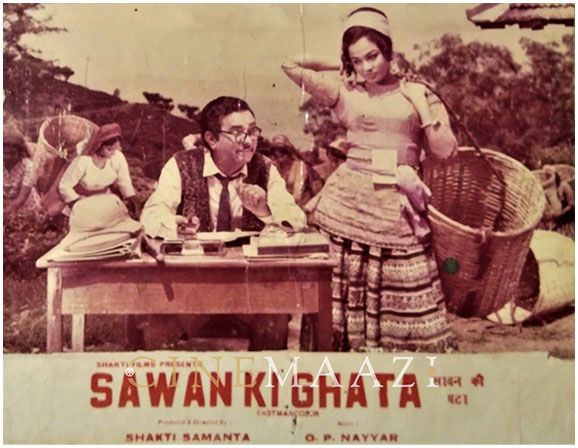

The year 1994 has not been the happiest of times for the Marathi film industry, industry, virtually fighting a grim battle for survival. The state Government of Maharashtra appreciated the plight of the filmmakers, and introduced certain concessions-reduction of Entertainment Tax on tickets by 50 percent, plus giving a kickback (not exceeding Rs. 16,00,000) to the producers from the Entertainment Tax collected. These concessions have failed to rescue the industry. During the year 1994, there was one solitary box office hit, Dada Kondke’s Sasarche Dhotar. The only other film to cover its production cost was Chikat Nawara (1994), which incidentally is a remake of a Tamil hit. All other films ended in the red; and if a film is not successful at the box office, then the entertainment Tax refund scheme becomes a mirage for its producer.

Realization has now dawned upon Marathi filmmakers that they must get out of the rut. It is necessary to take a brief look at the history of Marathi cinema to sense the winds of change that seem to be blowing.

Though quantitatively smaller than the regional cinema in south India and Bengal, the Marathi cinema is proud of its antecedents and its pioneering role in India, for it was in the state of Maharashtra that the Indian film was born. However, since independence, it has been all uphill, with the Hindi cinema, like Big Brother, monopolising most of the 1200 cinemas in the state, leaving a mere 200 halls to play Marathi films. In the 1960’s the once vibrant Marathi drama made a comeback, drawing away the educated classes from the cinemas. And then came the biggest blow-TV! Television was introduced in 1972 and rapidly made inroads into the rural areas where cinema had been able to hold its own. Within 10 years, 28 out of the 30 districts were covered by colour television.

With the rural audience as its backbone, over the past three decades three formulas evolved. These were family dramas, cheap comedies and stories with village backgrounds. Marathi producers were restricted by, virtually, shoe-string budgets, while the list of popular artists could be counted on the fingers of one hand. Of course, there were some sporadic efforts to break away from these formulas. Satyadev Dubey made Shantata ! Court Chalu Ahe (1971) on Tendulkar’s stageplay of the same name. This was in 1970, and the film was photographed by Govind Nihalani who later became a luminary in the Hindi parallel cinema. There were two other significant efforts in the early 80s, Dr. Jabbar Patel’s Umbartha (1982) and Amol Palekar’s Akriet (1981), but with indifferent box office reactions, these films did not establish a trend.

Unlike Hindi cinema, the gap between Marathi commercial cinema and the parallel cinema is not all that wide, but unfortunately the Marathi cinema has been unable to establish a link with international cinema. Even if results do not measure up to expectation, they have been noted. In 1994, despite being a bad year, we have seen wins of change inasmuch as out of 20 films, eight-show definite signs of having been influenced by the awareness brought about by the parallel cinema in India and abroad. For the first time, as many as six Marathi movies vied for places in the Indian Panorama section of the Indian Film Festival, whilst in the past no more than one or two producers promoted their films in this manner. The six films were Mukta, Bhasma, Warsa Laxmicha, Survanta, Mayechi Savali and Vazir. Of these, only the first named got the nod and was selected. Incidentally, Vazir was named Best Film of the year at the Maharashtra Government Film Festival, but the film, which Sanjay Rawal directed, did not gain any recognition in the National Film Awards and also failed to get into the Indian Panorama section this year.

The film from the Marathi film industry in Panorama is Mukta (‘Liberated Woman’) by Dr. Jabbar Patel. It deals with the relationship between a high caste girl and a Dalit boy and exposes a burning social problem. This film is certainly a telling cinematic experience.

Bhasma (‘Ashes’) directed by the successful commercial director Purshottam Berde, is based upon a popular novel by Uttam Bandhu Tupe. It deals with a downtrodden rural community. The family around which the narrative is woven lives in a crematorium, and the protagonist of the story is determined to break away from the shackles of the community to which he belongs, by giving his children a proper education so that they may hold their heads high in society. The theme of revolt against tradition has been powerfully portrayed and this effort is full of sincerity.

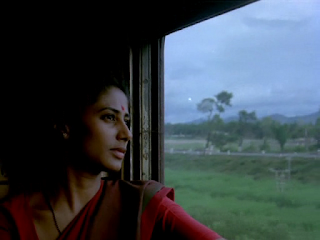

Ramdas Phutane established his credentials when he produced Samna (Confrontation, 1974) which was the official Indian entry at Berlin in 1976. His new directorial effort is Surwanta which depicts the trials and tribulations of womenfolk. These women are part of the seasonal workforce which works on the sugar plantations. Surwanta is one such woman. Ramdas Phutane has included songs in the film, a concession to the box office, but has cleverly utilized the medium to stress upon the plight of women in the neo-rich segments of Maharashtra society.

Trailer of Limited Manuski starring Rajit Kapoor and Gopika Sahani.

Bhagarwadi is also the name of a small hamlet occupied by a shepherd community in Western Maharashtra, and Amol Palekar returns to Marathi Cinema with this film. Steeped in the film society tradition right from his college days, Amol Palekar has been closely associated with experimental Marathi drama. He came to the Hindi cinema in the 1970s and appeared as an actor in films by Basu Chatterji and Hrishikesh Mukherji. He had nursed the ambition of directing his own films right from the beginning, and this dream of his became a reality in 1981 when he directed Akriet. Though his film brought Amol Palekar wide recognition as an accomplished filmmaker, it failed to make waves with the audience. Akriet was shown at the Indian Panorama section of our Festival in 1982 at Calcutta. It bagged an international award at the Nantes Film Festival, and received rave reviews from the American film critic Hobberman. Amol Palekar later tried his hand at Hindi cinema, making two films, Ankahee in 1984 and Thodasa Romani Ho Jaye in 1992, the first was awarded the National Best Music Award. Amol Palekar also dabbled with the small screen and has made a number of serials in both Hindi and Marathi.

His new Marathi film Bangarwadi is based upon a novel by the noted writer and Sahitya Akademi award-winner, Vyankatesh Madgulkar. The novel was published way back in 1955 and had caught the attention of the of the illustrious V. Shantaram. Shantaram acquires the film rights, but never made the film. The novel has also been translated and published in English under the title of Village Had No Walls. It is considered to be a classic in Marathi literature. As a writer, Madgulkar has a number of Marathi films to his credit, including the blockbuster Sangte Aika (1959) which ran for 132 weeks at one theatre, this being a Tamasha subject. He has also written the script and dialogue for Amol Palekar’s new film. The locale is the princely state of Satara during World War ll, the characters coming from the shepherd community. Amol Palekar has a cast of all-new talent, with the exception of the veteran Chandrakant Mandhare. The musical score comes from Vanraj Bhatia.

Directed by Sanjay Surkar, Kaif (Intoxication) deals with Maharashtra’s political scenario and is another new film to consider. It has been written by Vijay Kuwalekar, editor of the Pune daily Sakal. The other film that needs to be mentioned is Painjan (Anklet, 1995) which has been written by the noted actor Sadashiv Amrapurkar, and is in the suspense genre. Marathi cinema has not exactly arrived at the crossroads, but the fact that efforts are being made to produce films quite removed from the time-honoured ‘formulas’, augurs well for its future.

This article was originally published in Indian cinema's 1994 issue. The images used are taken from the original article and the internet.

Tags

About the Author

.jpg)