When Melody Ruled the Day

The Hindustani Film Song is a twentieth-century musical phenomenon. No other modern musical form from any part of the globe, including jazz, can boast of such diversity, richness, subtlety and reach. It is the Hindustani or Hindi (inclusive of dialects like Avadhi, Bundelkhandi, Bhojpuri, Deccani, amongst others, that have enriched the Urdu language) film song that has cut through all the language barriers in India to engage in lively communication with a nation where more than twenty languages are spoken and, despite the havoc wrought by the forces of progress, scores of dialects still exist.

What makes the Hindi film song unique is that it exists solely because it has been commissioned to fulfil certain demands made by the script and the finished film. The song has myriad functions in a commercial film especially those produced in Bombay. Indeed in a cinema that has had scant regard for script-writing since its inception, the spoken word (dialogue) - and especially the song - are the two devices available to make the film come alive memorably if only for a few minutes, thus giving credence to the observation made in another context by the great Dadaist Man Ray that even the dullest of films has five very interesting minutes in it!

This snide digression notwithstanding, it would be safe to say that the song had played a pivotal role in Indian cinema in general and the Hindustani or Hindi cinema in particular since the talkies came to India in 1931. How is it that only Indian films had many songs in them regardless of the genre they belonged to? It did not matter whether a social drama, historical adventure, comedy or mythological was being produced, songs were bound to be an organic part of the finished film. No other cinema in the world had this peculiar characteristic.

In Hollywood, with the coming of sound the musical was discovered - partly from looking back upon the spectacular song and dance stage entertainments produced by such moguls as Florence Zeigfield and Errol White and adapting many aesthetic ideas from them, including those related to choreography. However, the American musical was an autonomous cinematic form which, in the hands of a master, could achieve or uncover the truth despite the patently artificial means used in the search. This was one of the many genres of filmmaking in vogue in Hollywood through the '30s into the early '60s. The average film there did not have songs in them. The Chinese also produced musicals as an independent genre and based their productions on the triumphs of the Peking Opera. On the other hand, the Japanese drew inspiration from American films and the full-tonal scale of European music to augment their own five-tone system and produced musicals with a distinctly local flavour. But in Japan too, other genres of filmmaking flourished without songs. Only in India did vocal music wield such overwhelming power in every kind of film. The western-educated Wogs (Westernised Oriental Gentlemen) regarded this influence as pernicious without even understanding the phenomenon.

Long before the cinema came to India an active musical theatre had come into being. The plots during British rule in the second half of the last century dealt mainly with mythological tales or historical ones. The message, so to say, a patriotic one of overcoming the foreign oppressers, was concealed in the medium! Since India already had such a vast, varied and rich musical tradition, songs based on classical ragas and folk melodies became the energising force of such theatrical forays into the world of socio-political reality. By the time sound came to Indian films, musical-theatre was a very popular source of entertainment in Maharashtra, Gujarat, Bengal, Karnataka, the Madras Presidency (Tamil Nadu) and Northern India stretching from undivided Punjab to United Provinces (Uttar Pradesh) and Bihar. Vocal music had become a part of the Indian psyche. It would not be an exaggeration to say that the Indian genius expressed itself best through song. Are not the lyrics of Vidyapati, Kabir, Meera and hundreds of other anonymous bards proof enough? It was, therefore, only natural that the song becomes an integral part of the Indian sound film and the Hindustani or Hindi productions form Calcutta, Lahore, Bombay and Pune immediately accepted it much to their benefit.

The Second World War was still a few years away, as was the technological revolution that came in its wake, especially in communications, that once and for all robbed protected cultures like ours of all privacy and made them prey to all kinds of socio-political influences from the Occidental world and not necessarily for the best. The radio and the newspaper made this possible.

First Phase

In its phase (1931-45) the Hindi film song, like its counterpart throughout the country, was a judicious mixture of well-known classical ragas and folk tunes of overtly religious and directly spiritual overtones. Sometimes a composer used either form of music independently to great effect - most of them came from a classical background. In Calcutta, Raichand Boral and Timir Baran Bhattacharya were established Hindustani musicians. Boral was an accomplished tabla player and Bhattacharya a sarod player of immense promise. Pankaj Mullick too was not unfamiliar with ragas although he won fame for his more eclectic song compositions and his orchestral adaptations of English military bands as backgrounds to them.

In far-off Bombay a court musician Ustad Jhande Khan, bypassed by history and science, was trying to earn an honourable living as a composer of film songs. A master of khayal singing, Ustad Mushtaq Hussain Khan Bariellywale, was making similar efforts in Calcutta and Bombay. Madhu Master, Anil Biswas and Sajjad Hussain were accepting the emerging film song as a new form of expression and contributing to its evolution. In nearby Pune, Master Krishna Rao and Keshav Rao Bhole, not to forget the cherubic boy wonder Vasant Desai, were trying to create lovely new melodies out of the old repertoire of Marathi Natya Sangeet or music of the (now urban) fold theatre that was so successful in small town s and cities. But none of the Bombay-Pune composers could fully realise their dreams for they never had really versatile singers at their disposal. True that in Bombay artists like Master Nissar, Jahanara Kajjan and Farhad Jahan Bibbo (who later married one of the late Pakistani President Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto's uncles) were there and in Pune was the gifted Shanta Apte. But they were by training and temperament classical singers.

The song Do naina matware from Meri Bahen (1944) was sung and performed by K L Saigal

End of the Age of Innocence

With the passing of Saigal the age of innocence came to an end. Even able colleagues like Pankaj Mullick (despite the military bandmaster's phrasing in his singing), the slightly coy but very capable Kanan Bala and, of course, the consistently competent Uma Shashi, had to concede ground to new artists who were more in tune with the times. The Second World War had made some major changes in people's perceptions of the world around them and with that the music that was emerging from major social and psychological changes that were coming about.

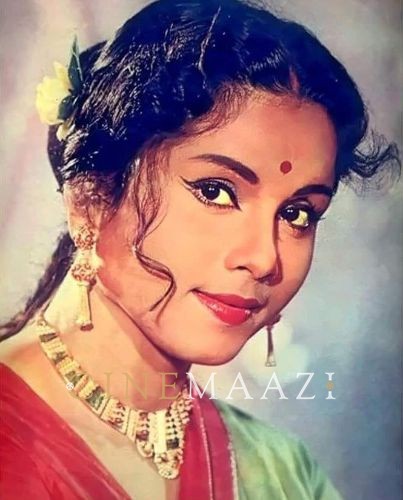

The film song which had till then been a vehicle of tempered, civilised emotions in a distinctly literary grab, suddenly found itself accommodating the needs of the times. The musings of Wali Saheb, Dr. Safdar Aah, Pandit Indra, Arzoo Lucknawi, D.N. Madhok and Zia Sarhady (to become within the next few years the torch-bearer of the left-wing tradition of filmmaking with works like Hum Log (1951), Foot Path (1953)) were per force making way for a more open appraisal of life. In a 1950 film called Samadhi, the dual nature of Nalini Jaywant's screen personality suddenly became evident. Her innocence came through very naturally, laced with potent sexuality as she sang (to the young Lata Mangeshkar's playback) Gore gore o banke chore, kabhi meri gali ayaa karo (Do come by where I live, fair and sprightly boy).

Nine years earlier in 1941 Dalsukh M. Pancholi produced a serio-comedy in Lahore called Khazanchi. It became a huge hit because of the music composed by a former dentist called Master Ghulam Haider, who came from a family of traditional musicians called Mirasis who had in earlier times sung raga-based shabadh kirtans from Guru Granth Sahib as ragis in Gurdwaras. Haider had sung a duet in the film with a young singer he had discovered - Shamshad Begum. She had a voice that was strong, transparent, melodious and earthy. The song Sawan k nazaren hain (Behold! The scene of the monsoon) became a rage, as did others like Diwali phiraa gayi sajni (Diwali is here again, beloved); Man dhire dhire rona (Cry slowly dear heart).

In a career that lasted less than ten years in India (he left a year after the partition in 1947) he changed the conception of the Hindustani film son. He wedded strong assertive melodic lines with an articulate beat usually derived from the store-house of pulsating, Punjabi rhythms. A lesson that was so profitably imbibed by a young Lahori prodigy called O.P. (Onkar Prasad) Nayyar who came into the limelight with his very first film Aasmaan in 1952.

Haider had, without intending to, become the leader of the Lahore school of film composers. Apart from his star pupil Shyam Sundar (who died so young), there were talented musicians like Husnlal Bhagatram, their elder brother Pandit Govindram, Rafiq Ghaznavi, Salim Iqbal, Feroze Nizami, and Jnan Dutt. They, like their master, employed a wholly indigenous technique of composition with tricky and sinuous melodies and captivating background scoring even when they used Western instruments and orchestral colouring they did it with freshness and originality. There are many who believed that the Lahore school created a body of work that would stand the test of time more readily than the efforts of composers who came after them. Another great service that Ghulam Haider had rendered to the film song was to discover Noorjahan, arguably the most expressive and most powerful female in the history of Hindi film music. Those who remember Ankh micholi khelenge (Hide and seek! We shall play), Umange dil ki machli (Heart's desires soared), Awaz de kahanhai (Call out to me, beloved), Kya ye tera pyaar thaa (So this was your love, was it?) will heartily agree.

The holocaust that resulted in the partition also brought about a need for chastity and purity in people's lives. This view was reinforced by the proponents of the Arya Samaj who had migrated to India from East Punjab. Many of them had found employment in the Bombay film industry and soon made a name there. Among them were Ramanand Sagar, B.R. Chopra, Devendra Goyal, Raj Kapoor, and others. They very quietly and effectively launched the cult of virgin worship. The heroine, regardless of her outer trappings of sensuality, had to convey to the viewer her virginal purity; there was no question of her asserting her sexuality. In its most open and healthy form, sex in films was taboo and could only be smuggled in as a necessary evil - like the hot water bottle. Seen in this context the phenomenal rise of Lata Mangeskar must also be attributed to an extra-musical reason.

The Phenomenal Lata

The daughter of Master Dinanath Mangeshkar, one of the really fine exponents of Marathi Natya Sangeet, Lata had to begin very early (at thirteen) in order to support family impoverished by the sudden demise of her father. Despite many hardships, she learnt classical music from such as Anjani Bai Malpekar, and Professor Amanat Khan (brilliant pupil of the venerable master Rajab Ali Khan Saheb of Dewas) while pursuing a career as a playback singer in films. Her voice retained its exquisite sweetness and malleability over a period of ten years - from 1948 to 1958 and had such tonal purity that you could dune an instrument by it.

.jpg/1%20(8)__544x480.jpg)

Perhaps an early exposure to the duplicity and moral degradation within the film industry made her turn away from the worldliness and seek emotional sustenance in a less troubled private world. The result of this experience was startling: her singing had an innocence and naiveté that was completely at odds with the trying world she had lived in. Thus when she sang (playback) for adult heroines in films her songs, in retrospect, were a surreal counterpoint to the amorous desires of the actresses concerned. This Hegelian accident of intention and execution involuntarily helped perpetuate the myth of the screen heroine as a snow-white virgin - made necessary by people who had lived through (and in many cases taken part in) the carnage of the partition and needed all the hope in the world to face life again and seek expiation for their real and imagined sins.

Lata Mangeshkar became the richest and most popular playback singer in the history of Indian films and also an extremely influential figure within the Bombay film industry. Her rendering, despite astonishing technical skill, lacked for the most part a sense of (adult) truth. But once in a while when this gap was bridged then the results were truly remarkable. Examples are here rendering of Bedard tere dard ko seene se laga ke (Heartless one! I cling to your memory) for her mentor Ghulam Haider; Chanda re jaare.. (Keep my secret, dear moon) composed with great delicacy by Khemchand Prakash; Tum naa jaane kis jahan mein kho gaye (Where did you lose yourself, love), a cry from the heart by Sachin Dev Burman; Mitti se khelte ho baarbaar kis liye (Why must you play incessantly with mortal clay?); The duo Shankar-Jaikishan's tribute to her musicality and Muhabbat aisi dhadkan hai (Love is a heart beat...) by the exceptionally gifted C. Ramchandra.

Heroines and Singers

The song, to state the obvious, was the most important component of the Bombay film. In its kernel was hidden the film's message: the director's true intentions. Since the stories had a monotonous sameness about them, without the élan or creative vitality evident in the folk theatre, it was left to the director to bring a measure of elegance, sophistication and artistic integrity to his work through the songs. A lot of attention was paid to the lyrics, the tune, the singing and finally the picturisation so that it appeared to be a film within afilm, a testimony to the filmmaker's artistic credo. The singer was chosen with great care in most productions regardless of the budget available.

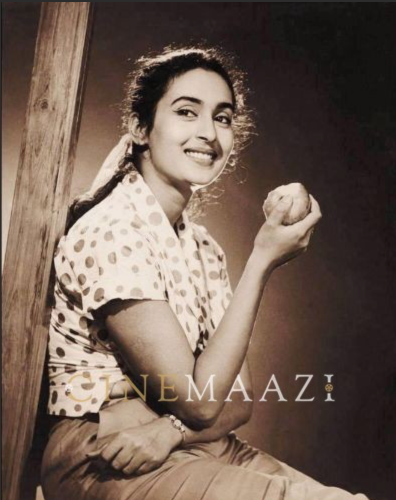

The women singers in the pre-Lata era were from the professional singing classes. Most of them were classically trained and sang their songs in a full-blooded manner highlighting the emotional content of the song including the sexual and sensual elements. Amongst them were Khursheed and Noorjahn who, despite their youth, had a wide knowledge of the emotions that actually rule the thoughts and actions of men who run the world... with such perverseness and lack of sensitivity and intelligence. These two singers projected this awareness in their song with great ease. But the one singer who could not shrug off the injustices of the world with irony and insouciance was Raj Kumari whose songs had an overpowering intensity that could neither be confronted nor ignored. A case in point is Ghabrakejo hum sarko (In utter despite I bang my head) composed by Khemchand Prakash and written by Naqshab. Director Kamal Amrohi and composer Khemchand Prakash used her voice to underline the eternally tragic in the film Mahal (1949) and Lata Mangeshkar's to express the sad longing of youth. Both sang for the young heroine Madhubala whose screen persona simultaneously projected girlish innocence and womanly maturity.

The heroine was in reality a more important person in Bombay films than the hero, despite the fact the latter got paid more and hogged the best lines in the script and the marquee. What after all was a leading man like Raj Kapoor without Nargis, or for that matter Dilip Kumar without Nalini Jaywant or most of his heroines including Madhubala, Nargis, Meena Kumari and Vyjayanthimala. How effective would Dev Anand be without Geeta Bali in his early films or Nutan, Vyjayanthimala and Waheeda Rehman later on? The woman was never a foil to the man in Hindustani films, quite the contrary. Hence the role of the female playback singer was significant since the song was given so much importance in the very conception of the film. The heroines willed life into a film and their playback voices into them. The men, in keeping with the contrariness of the coding systems of this cinema, only appeared to be the keys to the scripts when in reality they were the locks!

Songs sung for the leading lady and occasionally other female characters in the film were vehicles for multi-layered thoughts and feelings. The one singer who could do this with exemplary emotional integrity was Geeta Dutt whose voice, sometimes under strain because of her physically demanding lifestyle and high-strung personality, could render a very wide range of emotions and had an inner fire that vindicated the song's existence. She could spiritualise a lyric and make it sensuous at one and the same time. A torch song like Suno gajar kya gaye... (My how time flies!) also becomes a perceptive comment on the passage of time; the pastoral Thandi hawa kali ghata... (Dark clouds and cool winds have arrived in a trance); Nanhi kali sone chali (The little bud is going to sleep), a lullaby worthy of Brahms, and Jaane kya tune kahi (What was it that you said...) an eternally feminine tease, speak volumes for her artistic range as a singer and make us mourn in memory of her life so sadly cut short through emotional damage.

Geeta Dutt's Jaane kya tune kahi picturised on Waheeda Rehman from Guru Dutt's masterpiece Pyaasa (1957) was instrumental in the narrative to introduce the lead characters.

The Men: Rafi, Talat, Mukesh

Among the male playback singers the most popular, versatile and happy-go-lucky was classically trained Mohammed Rafi. Under the loving tutelage of the famous Ustad Behre Waheed Khan of Kirana he quickly became a very able khayal singer but like Lata Mangeshkar, he had to give it up because of demanding family responsibilities. His generous, easy-going nature made him well-loved; he could only respond fully to farcical songs sung for comedians. With other material his attitude was scrupulously correct and tuneful, though not always inspired. Despite enormous success in film music he seemed to secretly mourn the loss of a career in classical music. He could when pushed be heard to advantage in songs like Suhani raat dhal chuki (The velvety night has descended); Hum bekhudi mein tumko... (In a trance I call out to you); Aye na baalam... (The beloved comes not...) and Isharon isharon mein dil lene wale (You who capture my heart with a glance).

Since the lyric was all-important as it carried vital information about the characters and situations in the story it had to be interpreted with the greatest care. Two of the best exponents were the Urdu-speaking representatives of the Gung-O-Jaman civilisation - Talat Mahmood from Lucknow's Marris College of Music, and Mukesh Chand Mathur from Old Delhi. Both were detectives-of-the-soul. If Talat worked with a Sherlock Holmes-like precision in uncovering the mysteries of the human heart in song, Mukesh went a step further and probed even more lucidly in the manner of Holmes' almost clairvoyant elder brother Mycroft! Both had problems with their voices, but of a different nature.

Talat, in the beginning, had a powerful melodious tenor voice; evidence of which is still available on tape and disc. That voice, however, disappeared by 1951-52. When Amiya Chakraborty's Daag was made in 1953, Talat sang for it in his new avatar. His voice was not soft, sweet... pianissimo. His silken legato enabled him to go up and down the vocal register with unbelievable ease. But such a voice needed a great deal of looking after and Talat the gourmet and heavy smoker ignored the possibility of disaster. Over a period of fifteen years his voice gradually grew darker and by degrees disappeared. He sang hundreds of memorable songs in his prime and after. How can one forget Sham-e-gham ki kasam (I think of you in the palpable sadness of evening), Aye mere dil kahin.. (Let's go elsewhere restless heart), Jayen to jayen kahan (Where does one go from here), Ana hi parega (You'll have to come dearest), Pyar par bus to nainhaye... (I know not my fate in love). Talat's singing like his personality was mellifluous and changing trends in cinema and society finally bypassed him as singers were phased out in favour of howlers!

Mukesh was a survivor. Without making too many compromises he tailored his songs to suit the times. Fond as he was of the good things of life he did not abuse his highly expressive but not too flexible light baritone voice that needed a couple of hours to warm p and get into tune. As an interpreter of song he was supreme. Like a seismographer alert to the slightest tremor in the bowels of the earth so was Mukesh sensitive to the hidden nuances in the lyric. Amongst a host of masterpieces are pieces like Dil, jalta hai, to jalne de, Awaara hoon..., Choti si yeh zindagi re (The small woeful tale that is life), Hamein aye dil kahin le chal (Take me dear heart far far away), Mera juta hai Japani, woh subah kabhi to aye gi (The dawn shall come yet!), Phir na kije meri gustakh nigahi ka gila (Don't chide me then for my bold glances). Not all singers were lucky in finding the right composers or producers to put their talents to use. A prime example was and is Manna Dey, nephew of the legendary Krishna Chandra (K.C.) Dey, the blind kirtan singer and character actor from New Theatres, Calcutta. Probably because of his classical training, Manna Dey was slotted for a particular type of song. He was never allowed to show his versatility, despite being gainfully employed. His soul-stirring kirtan-like Chale Radhe Rani (In tears goes Radha, away from her beloved Krishna) will continue to move listeners over time.

The Composers

No song can come into being without a composer or lyricist. In Bombay the laws of creativity have followed a peculiar path. While the song writers were known Urdu or Hindi poets, composers were from many parts of India, including Bengal. Three of the finest - Anil Biswas, S.D. Burman and Salil Chowdhury - were from there and only Biswas knew the subtleties of the Hindustani language and its accompanying dialects. Yet all the three composed haunting melodies set to words that were not a part of their childhood psyche.

In the '40s and '50s, Bombay was teeming with music directors. Amongst them were the scintillating duo of Shanker-Jaikishan, Madan Mohan (Kohli), Roshanlal (Nagar), both introspective artists, the under-rated N. Dutta (Treya) and the dark horse from Patna, Chitragupta; not to forget Ghulam Mohammad, a talented tabla player of the Delhi gharana who also composed flowing film melodies. Between them they composed a body of work that was both varied and rich and could stand up in any company.

Sajjad Hussain made his debut in Bombay in the middle thirties but really came into his own about a decade later. He had by then developed a taste for intricate melody inspired by ragas and folk music coupled with a flair for western rhythms, particularly the beat of the waltz. That he managed to combine the two and create a new aesthetic in the film songs is in itself a considerable achievement. With Noorjahan he created Badnam muhabbat kaun kar (Who wishes to bring ill upon himself?) that had a most beguiling quality of sadness and defiance. Structurally it was novel, with the taans, murkis and khatkas in Noorjahan's resonant voice blending miraculously with the two/four rhythm, the flowing melody rendered even more exquisite by the staccato piano accompaniment. He took note of this musical adventure and used it later in a Lata-Talat duet in Sangdil (1952)- Dil mein sama gaye sajan (You've merged in my heart, beloved). This song, while deriving its outer structure from the older song, employed sparking, new harmonics and became a dynamic, fresh creation. One does not know if Sajjad had heard recordings of pre-18th century European orchestral music but he had somehow imbibed it. It is quite possible that he and later O.P. Nayyar, heard them from their Goan arrangers, many of whom were schooled in Western classical music.

Sajjad used these valuable lessons with great tact in his own compositions, for instance, in the Geeta Dutt-Asha Bhosle duet in Sangdil - Aja basane naya sansar, aja (Come with me to a new world) he uses the call and response technique of old European (Spanish/Moorish?) music in a song with metaphysical resonances. In Sangdil again is his completely original treatment of Mirabai's timeless bhajan - Darshan pyaasi aayee daasi (Your slave's eyes thirst for a glimpse of you, lord). The voice and the instrumentation merge into a crystalline whole, imbuing the song with tremendous pathos. His career was relatively short because of his perfectionism and mercurial nature. He never had any intentions of adapting to changing market trends and rather regally wanted the market to accept him as he was and celebrate his music. Had that been so then masterpieces like Loota dil mera haay abaad to kar (Having ruined me), Aaj mere naseeb ne mujhko rula rula diya (My fate made me cry...) from Hulchul (1951) and the Sangdil gems: Kahan ho kahan ho (Where art thou, maker of this universe?), Woh to chale gaye aye dil (The loved one has gone, dear heart), would have become a part of our national musical heritage instead of fuel for conversation amongst connoisseurs.

O.P. Nayyar, like Sajjad Hussain, was/is acutely aware of melodic structures and rhythmic patterns. His compositions, the best of them (and there are many examples) for all their spontaneity are mathematically precise. He too is secretly obsessed with correctness although his own life has been, to put it euphemistically, volatile and lacking in logic. His knowledge of Punjabi folk music, organic structures of certain elemental ragas and openness to outside influences, particularly to that of Latin America music, has made him at his best a scintillating composer and at his worst a fair one. He has been accused of being too versatile for his own good and a purveyor of formula music. Both the charges have some truth in them, but Nayyar at his best is something else altogether.

Compositions like Main soya ankhiyan meeche (In a reverie I lay); Chota saa baalama (My little darling) ... Jaaeye aap kahan jayenge (Go where you will), Piya mein hun patang to dore (I am your kite sweetie and you are my string); Mujhe dekhiye hasrat ki tasveer hun main (Look at me I am the very picture of hope); Isharon, isharon mein..., (Beckoning with your eyes); Yeh lo mein hari saiyyan (You win, sweetheart); Puchho na hamein hum unke liya... (A present for you - Don't ask me what Bekasi hadh se gar guzar jaye (when the cup of sorrow spills over); Jaaeye aap kahan jayenge (Go where you will) speak for his stature as a composer; his ability to unite all the elements in his song and fuse them into a thing of musical beauty put him in the same league as Jelly Roll Morton and Sidney Bechet - great men of classical jazz and masters of form.

O P Nayyar's composition voiced by Asha Bhosle and Mohammed Rafi for the film Kashmir Ki Kali (1964)

Lyricists were either poets like Majrooh, Jan Nissar Akhtar, Sahir Ludhianvi and Shakeel Badayuni, Raja Mehdi Ali Khan, Kaifi Azmi or just song-writers like Rajendra Krishan, P. L. Santoshi and Shailendra. More often than not they had to write words to an already composed tune, relying on their native talent to fathom the necessary poet, psychological, social insights into the character or characters singing the song. Since it was also to be picturised the lyricist had to work a shade harder than the director or cameraman to ensure that his words actually worked visually as well as musically.

Usually song writers worked in tandem with the composer: Shakeel and Naushad, Shailendra and Hasrat with Shankar-Jaikishan, Majrooh with S.D. Burman and O.P. Nayyar in mid-career, then, as in the beginning, with a host of music directors. The two giants of this profession are no doubt Majrooh and the late Shailendra. Majrooh, a major Urdu/Hindwi poet and also a prolific song-writer who has written to order four thousand songs for three hundred and thirty films over the last fifty years, is difficult to approach for consistency and quality. Four hundred of his songs shall surely live and in their range and scope equal the surprising efforts of Hugo Wolfe, the great German song (Lieder) writer. It is all the more remarkable that his songs have all been written at the behest of others.

Shailendra, who died in 1966, had an exceptional ear for turns of everyday speech and the poetry of the Hindwi dialects. He could with seeming lack of effort turn a simple proverb or figure of speech into a song. His Dil ka haal sune dilwala sedhe si baat na mirch masala or Ramaiyya vasta vaiyya meine dil tujhko diya can never be translated into any western language because of their indigenous rootedness. Majrooh's Hum hain rahi pyar ke, hum se kuchna boliye and Hum aaj kahin dil kho baithe too, cannot be translated for identical reasons. The best works of these two masters are models for would-be lyricists who wish to achieve a perfect blend of clarity and economy in their work.

The Hindustani film song in its golden period embraced vast areas of human emotions and experience and became an independent art form that enriched while it entertained. Its mesmeric pull can still be experienced after nearly thirty years. It is quite likely that it may well survive into the next century and later.

This essay was originally published in the book Frames Of Mind- Reflections Of Indian Cinema edited by Aruna Vasudev. The images used were taken from Cinemaazi archive, the original essay and the internet.

Tags

About the Author

.jpg)