Cinema in India, from its inception, is considered a reservoir of stylistic iconography, fashion statements, cultural etiquette, and behavioral indicators. Films from Bombay held a massive influence on its audiences and thus, played an integral part in weaving the cultural fabric of the nation in the 20th century. Audiences used to hog theatre spaces to watch their favorite stars wearing designer costumes and speaking stylized dialogs in a language alien to everyday conversations, which they end up replicating in their personal lives. Thus, representation becomes key when discussing the medium of cinema, particularly Bombay cinema.

Courtesan films: A sub-genre of historical and social

Islamic culture or Islamic films is not strictly speaking religious films that propagate the Prophet’s teachings but instead, representing a cultural imaginary that is deep-rooted within the lived experiences of Muslim identity at a specific period of time.

If we look at the history of Bombay cinema, we get to witness the different influences and inspirations that went on to define and solidify Bombay cinema as an industry and a cultural monolith. From Hindu mythological tales, Parsi theatre tradition, Persian folk legends, Islamic culture, and Urdu language, Bombay cinema played an active part in telling a wide variety of stories and ways of living. One such representation is of Muslims and Islamic culture on the big screen which took over the aesthetics of Bombay cinema in a very unique way. Following Marshall Hodgson and Mukul Kesavan, it can be said that representing Islamic culture or Islamic films are not strictly speaking religious films that propagate the Prophet’s teachings but instead, represent a cultural imaginary that is deep-rooted within the lived experiences of Muslim identity at a specific period of time. Muslim identity are represented in different ways in films but, the most dominant of them is the genre of historical and social films.

Courtesans were prevalent as much in Hindu or, Indic tradition in the form of Raja Nartakis, Apsaras, Devadasis, as they were present in the Nawabi culture of Awadh in the form of tawaifs.

Muslim-historical depicted a period of history when India was ruled by the Mughals, Britishers and other political Islamic dominant regimes. Films like

Anarkali (1953),

Mughal-e-Azam (1960),

Taj Mahal (1963),

Humayun (1945) and many others are examples of Muslim historical. Muslim socials, on the other hand, confronted the problematics of Muslim socio-cultural life and acted as a voice for the Muslim identity. However, an interesting sub-genre emerged out of the confluence of these two genres – courtesan films.

A courtesan always appears as a marginal figure in Hindi films, an aberration to the smooth functioning of a society. She will only be accepted by the society once she is ready to leave her profession. Every courtesan figure in these films suffers from the societal shame thrown at them which ultimately makes them yearn for respectability.

Courtesan films represented a figure of a dancing woman in a court, mehfil, brothel, or, private gathering. But again, courtesan films become a broad term since they encompass the tradition and cultural imaginary that can transcend the socio-religious boundaries. Courtesans were prevalent as much in Hindu or, Indic tradition in the form of Raja Nartakis, Apsaras, Devadasis, as they were present in the Nawabi culture of Awadh in the form of tawaifs. Films like

Amrapali (1966),

Chitralekha (1964),

Utsav (1984) are some of the films which represented the courtesans coming from the Indic tradition and way of life but, the figure of tawaif became an object of obsession for most of the filmmakers and writers of the Bombay cinema in the 20th century which continues to exist even today. Muslim courtesan films, henceforth, became a phenomenon that pulled out the figure of courtesans deeply embedded within the forgotten mehfils of the eighteenth and nineteenth century Lucknow, Kanpur, and Delhi and projected them onto the big screen for the audiences to behold. Since, these films were looking back at a lost period in time and situate the courtesan or tawaif, as the central character, and their issues as the central conflict; they tend to blur the lines between the historical and social. Almost all of the films that have courtesans as the protagonists are contingent on the dramatic conflict surrounding the social perception around the profession.

Pakeezah (1972),

Umrao Jaan (1981),

Mughal-e-Azam (1960),

Tawaif (1985),

Sardari Begum (1996),

Mandi (1983), all of these films tell the stories of courtesans who are deemed unfit by the society and are therefore, relegated to the margins.

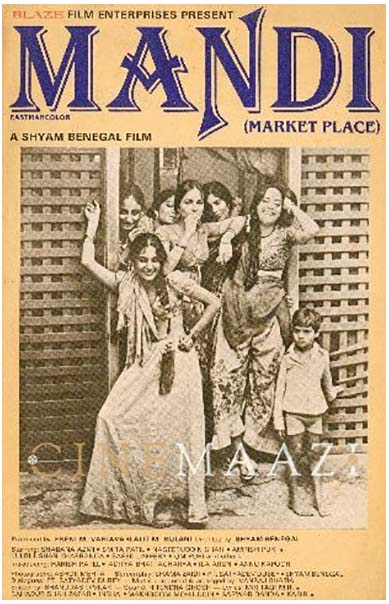

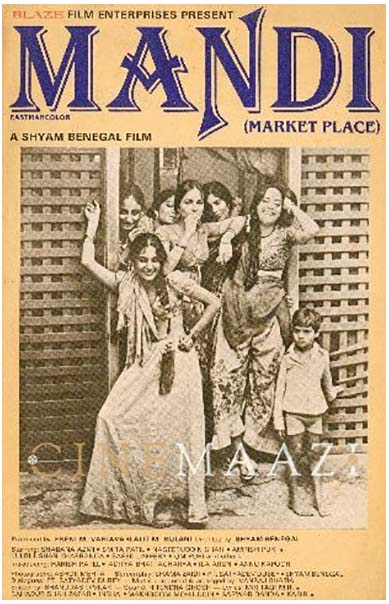

Shyam Benegal’s

Mandi (1983) perfectly depicts this reality by materializing it in the mise-en-scène where the brothel is shifted from the heart of the city to its outskirts.

"Mandi" (1983).

"Mandi" (1983).

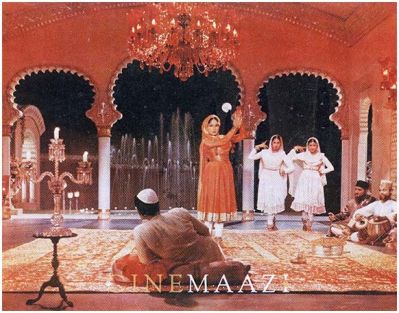

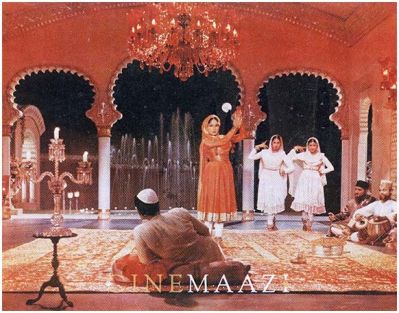

The performing space of the

mujra and the entire mehfil were central to the genre of Muslim courtesan films. Enclosed within an architectural idiom reminiscent of the Islamic/Oriental world, this space became the social space for the mehfil and performing stage for the courtesan. This space and its characteristics became a template and was shared by several films in this genre. It consists specifically of a rectangular space surrounded by curved or slightly multifoil arches, a collection of candelabras and chandeliers spread all across the space complemented with a lush velvety carpet spread out on the floor. The performer, in this case, the courtesan becomes the centerpiece as she performs for the onlookers seated around her. The craft of the courtesan form is dependent on the art of careful seduction and eroticism through the use of flowery language in the form of

ghazals,

sringara rasas, and virtuoso displays of classical dance forms. Through these several means, the courtesan claims an agency and leads the men in the audience through her gestures. Men become subservient and follow her lead. This subversion of the gender roles is reversed in the Muslim courtesan films.

"Pakeezah" (1972)

"Pakeezah" (1972)

A trip down the rabbit hole of history

A courtesan living in the eighteenth and nineteenth century Awadh for instance, is someone who held immense political and cultural capital. A figure like her was seen with utmost respect since she was considered the epitome of adab and tehzeeb (etiquettes and refined manners). ...However, it was the British who were responsible for the systemic decline of courtesans and their reputation. Veena Talwar Oldenburg in her research discovered important evidence which points to the British actions of penalizing and confiscating properties of Lucknavi courtesans for their instigation and aiding of the rebels during the 1857 rebellion.

But the picture is quite different when the pages of history are unfolded. A courtesan living in the eighteenth and nineteenth century Awadh for instance, is someone who held immense political and cultural capital. A figure like her was seen with utmost respect since she was considered the epitome of adab and tehzeeb (etiquettes and refined manners). Her formal training in language, poetry, music and performance was meant to display the opulence and highly cultured way of life in those times. Her place of dwelling which is referred to as kothas (brothels) was where she performed her mujra. ‘The sons of nobility were sent to these courtesans to learn etiquette and poetry, and probably the art of lovemaking,’ writes Rachel Dwyer (Dwyer, 2004). These brothels were supported by the patronage of the noble class and Nawabs who were frequent visitors to these places. However, it was the British who were responsible for the systemic decline of courtesans and their reputation. Veena Talwar Oldenburg in her research discovered important evidence which points to the British actions of penalizing and confiscating properties of Lucknavi courtesans for their instigation and aiding of the rebels during the 1857 rebellion. As an act of revenge, the courtesans faced heavy repression by the British regime through the passing of Cantonment Act of 1864 and Contagious Diseases Act of 1865, which made it official policy not only to relocate some of these courtesans to British cantonments, where they were made to sexually service European soldiers, but also to subject them to regular invasive medical check-ups to verify their disease-free status (Oldenburg, 1984). Further, courtesans faced successive repression in the years to come with the oncoming nationalist instincts and reforms. Their profession never thrived again. To make ends meet, several courtesans capitalized on their musical and dance training and shifted to radio and films for employment. What was once considered a respectable profession transformed into an immoral and deviant act by the time India became independent.

Bombay cinema in its post-independence era adopted a nationalist fervor that focused on inculcating values of social integration. In its nationalist framework, Bombay cinema preferred engendering a femininity that was selfless, sacrificial and always supportive of her husband and children. In due process, something that works in conflict with this accepted notion of femininity is always considered the ‘Other.’ The vamp in the 60s and 70s epitomized by

Helen, the femme fatale in the noir-inspired films,

tawaifs in Muslim courtesan films offered a different breed of femininity which became the selling point of these films. However, these representations were not immune to the meta-narrative setup by the all-encompassing nationalist and patriarchal forces. On looking closely, the vamps, femme fatales and courtesans by the end of the films are either made to comply with these narratives or else are killed or left abandoned, if chosen otherwise. Representation of courtesans in Bombay cinema, therefore, become an extension of the dominant nationalist discourse as discussed by Teresa Hubel (Hubel, 2012).

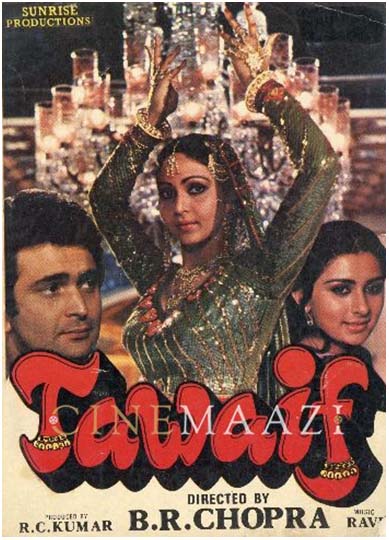

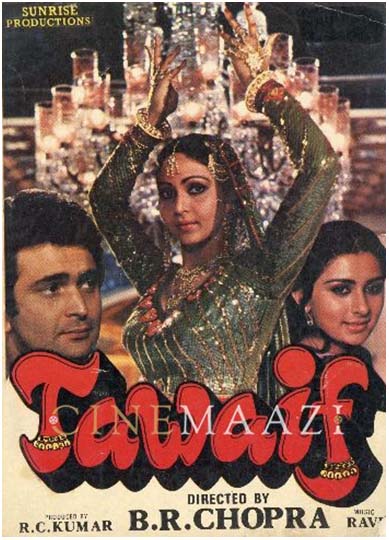

"Tawaif" (1985).

"Tawaif" (1985). as Sahibjaan performs

mujra for her lover Salim Ahmed Khan in

Pakeezah (1972). Throughout the film, Sahibjaan is conflicted and has a desire to leave her profession of a tawaif and get married to Salim. Her dramatic conflict lies in the fact that her profession will not be accepted by society and thus, she is unfit to enter into the heteronormative structure of marriage.

In

Umrao Jaan (1981),

Rekha as Umrao falls in love with Nawab Sultan making this romantic arc the central plot point of the entire narrative. Even in

J P Dutta’s

Umrao Jaan (2006), Umrao is portrayed as the suffering and jilted lover of Nawab Sultan. However, the source on which these films are based,

Mirza Hadi Ruswa’s novel

Umrao Jaan Ada (1905), presents Umrao as an intelligent, independent woman cultivated in both arts and seduction and is fully capable of looking after herself. Ira Bhaskar mentions in her book what Umrao declares at the end of the novel, ‘I am a woman of experience who has slaked her thirst at many a stream . . . I appear pliable and pretend to be molded by people when it is I who am molding them’ (Bhaskar, 2009). At the end of both of the adaptations, Umrao is left dejected and presented as a victim of social alienation which is very antithetical to the essence of the novel.

B R Chopra’s

Tawaif (1985) is another example of creating a narrative around the aspiration of a courtesan to enter the structure of marriage.

Rati Agnihotri’s Sultana is portrayed as a confident woman who always speaks her mind. But her accidental meeting with Dawood, played by

Rishi Kapoor, forces her to hide her identity. They both develop feelings for each other and because of some miscommunication, they are forced to play the masquerade of a pretend married couple in the society. A sudden shift in the behavior of Sultana takes over when she dons the persona of Dawood’s wife. She becomes an introverted, submissive and reserved woman.

...once considered a respectable profession, enjoyed by the nobility; the courtesans who held massive political influence and were gatekeepers of the refined culture, has witnessed a systemic attack over the period of time. Tawaif, etymologically comes from the Arabic word tauf or tawaf which means circling around and has zero derogatory connotations attached to it. But the term courtesan, tawaif, prostitute, dancing girls, sex-workers are used synonymously now.

What has happened is clearly a shift in the way Bombay cinema has chosen to represent courtesans on the big screen. What was once considered a respectable profession, enjoyed by the nobility; the courtesans who held massive political influence and were gatekeepers of the refined culture, has witnessed a systemic attack over the period of time. Tawaif, etymologically comes from the Arabic word tauf or tawaf which means circling around and has zero derogatory connotations attached to it. But the term courtesan, tawaif, prostitute, dancing girls, sex-workers are used synonymously now. The meanings and historicity of these different sets of words have been conflated into a single set. Bombay cinema in an obsession, fuelled by nostalgia, to recreate the lost time has resulted in further trapping the figure of the courtesan in a moral predicament. In an ironic fate, the rich heritage of song and dance in Hindi films which is outlandishly celebrated today, borrows its lineage from these women of culture who are now stripped of all their privileges and are living the life of systemic subjugation and exploitation.

Sources:

- Bhaskar, Ira, and Richard Allen. 2009. Islamicate Cultures of Bombay Cinema. Tulika Books.

- Hubel, Teresa. 2012. From Tawa'if to Wife? Making Sense of Bollywood's Courtesan Genre. Department of English Publications. Huron University College, Canada.

- Oldenburg, Veena Talwar. 1984. The Making of Colonial Lucknow, 1856-1877. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Dwyer, Rachel. 2004. Representing the Muslim: the “courtesan film” in Indian popular cinema. In Jews Muslims and Mass Media. Routledge Curzon. London.

.jpg)