Shashi Kapoor: The Actor and The Friend

Subscribe to read full article

This section is for paid subscribers only. Our subscription is only $37/- for one full year.

You get unlimited access to all paid section and features on the website with this subscription.

Not ready for a full subscription?

You can access this article for $2, and have it saved to your account for one year.

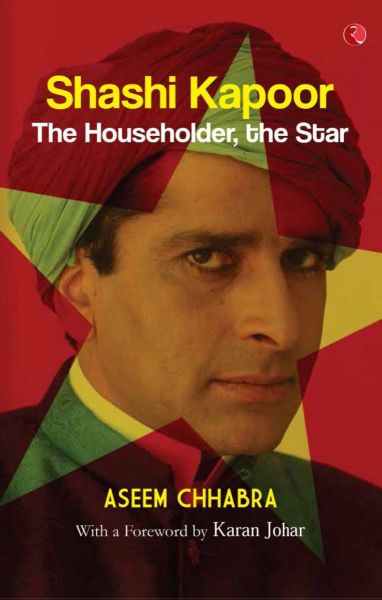

India’s first biography of Shashi Kapoor sheds light on one of the country’s most enigmatic personalities—an actor who straddles the worlds of commercial Hindi cinema, theatre and small-budget art movies; who is, at once, an earnest householder and a committed star.

In this rare book, we are offered glimpses of Shashi Kapoor, the family man—son of Prithviraj Kapoor, husband of Jennifer Kendal, and father to Kunal, Karan and Sanjna. We are led through Shashi Kapoor’s film career—his debut as a bright-eyed child-actor in Awara; his emergence, in the hectic 1970s, as India’s busiest performer—with a slew of hits including Deewaar and Trishul; and his rise to international prominence with Merchant–Ivory’s The Householder and a ‘trilogy’ of films on older men with fading pasts. Equally, we are provided with an astute analysis of Shashi Kapoor, the businessman—the proprietor of Film-Valas; the producer of Shyam Benegal films; and the distributor of Bobby.

With luminous and thus-far undisclosed stories by the actor’s family (Neetu Singh, Rishi, Sanjna and Kunal Kapoor), co-stars (Shabana Azmi, Simi Garewal, Sharmila Tagore), colleagues (Shyam Benegal, Govind Nihalani, James Ivory, Hanif Kureishi, Aparna Sen), and friends; a compelling foreword by Karan Johar; and stunning photographs from Merchant–Ivory’s archives, Shashi Kapoor, the biography—by one of India’s best-known film journalists—is as captivating as Shashi Kapoor, the star.

The following is an excerpt from Aseem Chhabra's Shashi Kapoor: The Householder, The Star.

On the recommendation of a Hollywood scriptwriter at MGM (Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer), Ismail had read a book written by the German writer, Ruth Prawar Jhabvala, who lived in Delhi with her Indian architect husband. Ismail was riveted by the story of The Householder and its ability to capture the nuances of Indian life. He passed on the book to James, who was equally captivated. Straightaway, the two contacted Ruth, who—known for her reluctance to talk to filmmakers—pretended on the phone to be her mother-in-law. Finally, though, the ruse collapsed, and after some hesitation, she agreed to meet them. One can only assume that Ismail and James charmed her with their persuasiveness, for—despite her husband's warning that the duo looked like fly-by-night operators—Ruth not only gave them permission to make a film based on her novel but also agreed to write the script.

Ismail and James, loath to let go of the dream star cast of Devgar, decided to involve Shashi, Leela and Durga once more, this time in the new project. But, before they could finalize the actors, Ruth expressed a concern. She thought Shashi was far too handsome to play the role of Prem Sagar, the hapless schoolteacher in The Householder. 'If you wanted to make a film about a poor, struggling tutor in some miserable school in Delhi, you probably would not cast someone like Shashi, who was so magnificent,' James tells me. 'He was a grand young man.'

Subsequently, when Shashi visited Ruth—his thick hair neatly cut, with a staid side parting—and spoke like the character he imagined Prem Sagar to be, Ruth could not help seeing him in a new light. 'So that's how I started [my association] with Merchant–Ivory Productions,' Shashi says."

It didn't take long for Shashi to grow close to James. 'I enjoyed working with Jim [as James was referred to by friends],' he says, `because he gave me the confidence [...] to do things my way, to use my talent, my intelligence, my sensibilities [to portray] characters in his films.

James, on his part, says that it was because Shashi was happy to immerse himself in a role, and allow his life experiences, susceptibilities and inclinations to interact with each part, that he enjoyed collaborating with the actor: 'Shashi was very easy to work with. He took direction well. And like any good actor, he sometimes offered me the choice of doing a scene another way—which I followed, if it made sense, if it fit in with my idea of the film and if it wasn't too violent a change in the dialogue. Shashi certainly, and all actors everywhere, fiddle with the dialogue—they think there is a slightly better way to say a line, or one word would be better than another—and I go along with that. Not always, but sometimes, yes.'

In the meanwhile, in Ismail, Shashi found a lifelong friend, and also a colleague he could at once admire and tease: 'Ismail Merchant, to me, is a hardworking, good producer. I don't think anybody can say that he is a bad producer. But he sometimes acts like a pigeon when he knows that he doesn't have money. [...] You know, when you point a gun at a pigeon [.. .] the pigeon closes its eyes, thinks that everything will pass away. So Ismail thinks and does things like a pigeon sometimes!' Shashi adds with a playful smile, 'So, when he has no money, he still makes the film. When he has no dates, he still gets the actors to work with him. It's amazing how he continues doing it!’

Even after three years in America I had never drunk wine and Shashi decided it was time I was introduced to the better things in life. 'If you have never tasted wine, then you have wasted your life,' Shashi told me. 'You must have a glass with me.' He corrupted me completely.

Shashi's rapport with Ismail, and his fondness for James, would have a direct bearing on his working relationship with them. They combined their immense talents for seven films made under the Merchant–Ivory Productions banner: The Householder, Shakespeare Wallah, Bombay Talkie, Heat and Dust—all directed by James Ivory—and three films by three other directors—The Deceivers, In Custody and Side Streets.

This has been reproduced from the book Shashi Kapoor: The Householder, The Star.

The banner image did not appear with the original publication and may not be reproduced without permission.

Tags

About the Author

Aseem Chhabra is a film journalist, freelance writer and film-festival programmer in New York City. He has been published in The New York Times, The Boston Globe, The Philadelphia Inquirer, Outlook, Mumbai Mirror, Rediff.com, has a regular colum in The Hindu; and has been a commentator on Indian cinema adn popular culture on NPR, CNN, BBC, as also ABC's Good Morning America, Associated Press and Reuters. Aseem is the festival director of the New York Indian Film Festival and the Silk Screen Asian American Film Festival in Pittsburgh. He is also the voice of Shadow Puppet #1 in director Nina Paley's award-winning animated film, Sita Sings the Blues.

Aseem is from Delhi, lives in New York, and visits India often. Ge can be followed on Twitter @chhabs.

.jpg)