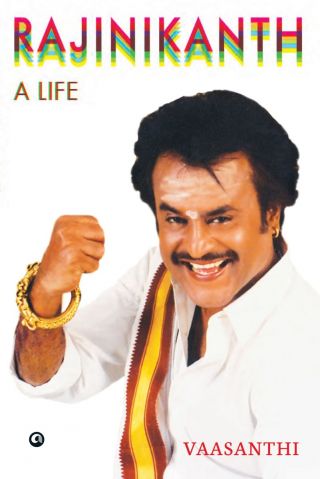

Superstar Rajinikanth defies all conventional analyses—no one has reigned supreme for as long as he has in the world of Indian cinema. With over 150 films under his belt, many of them blockbusters, he still plays the hero at seventy, and the devotion of his legions of fans has not waned during the forty-odd years of his stardom.

In a state that saw the Dravidian self-respect movement propagate atheism, fans worship his cut-outs and bathe them with milk and beer, as if he were their god. In a society famous for its pride in its language, it is curious that a Kannadiga whose family hails from Maharashtra, an outsider, should emerge as a 'thalaivar', or leader. With the death of the charismatic J. Jayalalithaa, a former actor, and M. Karunanidhi, who was a scriptwriter for films—leaders of the AIADMK and DMK respectively (the two main Dravidian political parties that have been ruling Tamil Nadu for more than sixty years)—Rajinikanth's fans believed there was a political vacuum that only he could fill. While the actor has been dabbling in politics, by making pronouncements on certain issues, including Jayalalithaa's policies, the Cauvery water sharing problem between Tamil Nadu and Karnataka, bomb attacks in the state and so on, it was only in 2017 that he promised to form his own party and contest all 234 seats in the 2021 assembly elections. For decades, his fans had been awaiting this moment, believing that he could solve all their problems and give them a life free from strife and governance free of corruption. His fan clubs went into high gear to turn themselves into the foundation of their thalaivar's political party, attracting more members and working on the ground all over the state.

For three years, every utterance of Rajinikanth's was analysed and debated even more vociferously than anything he has said in the past. Political opponents questioned his experience and pointed out that (even after forty years) he was an outsider who did not understand the undercurrents of Tamil Nadu politics; his detractors criticized the lack of a clear ideology behind his promise of 'spiritual politics'; political analysts who saw that Rajini was close to the BJP anticipated that he might enter into an alliance with them, allowing the right-wing party a foothold in the state. Ultimately, however, the seventy-year-old superstar withdrew from the political arena citing health concerns. The fans were hugely disappointed but understanding. With their continuing support and excitement for the next Rajini-starrer, he remains a giant in the field of entertainment.

Rajinikanth: A Life is the best account yet of the man who was born Shivaji Rao Gaekwad—once a coolie and a bus conductor in Bangalore and now virtually a god in Tamil Nadu.

Following is an excerpt from Rajnikanth: A Life by Vaasanthi.

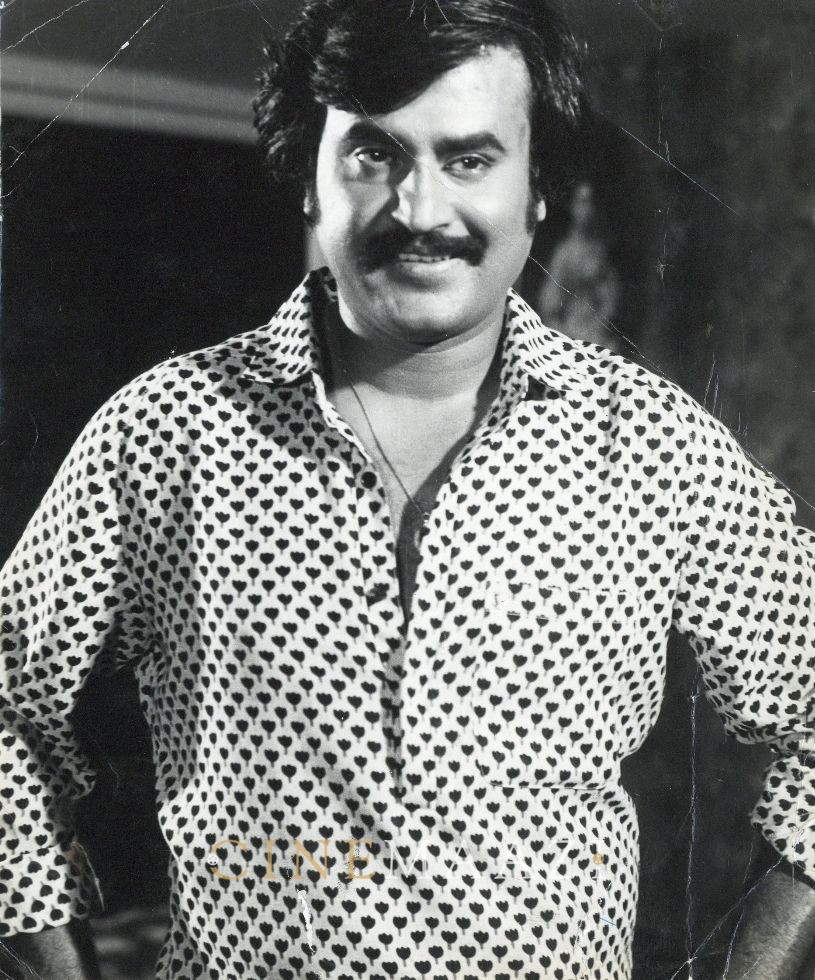

Shivaji played the role of Duryodhana in the play Kurukshetra, feeling a strange empathy with the character. He was moved by the love that Duryodhana developed for Karna, the underdog. Duryodhana was the bad guy in the story, but people noticed that so far no one had acted the part with such panache and style. Shivaji as Duryodhana lifted the mace with such nonchalance. Duryodhana would walk fast, deliver the dialogue with such speed and anger that he spit fire. He was kind, he embraced a friend who had been humiliated. He was generous, he was human. Duryodhana was not a villain. He became the hero. Shivaji became Duryodhana.

But Raj Bahadur had sown the seed in him. The lure of the silver screen became an obsession. ‘Don’t underestimate your talent,’ his good friend said. This became a mantra—whispering in his ears even in his dreams. He would wake up thinking: What is the harm in trying one’s luck? But he knew what his father’s reaction would be. He could visualize the scene. His father’s raging fury—‘Have you gone crazy? Have you looked at yourself in the mirror? Do you think people will spend their money to see such a face on the screen? This conductor’s job is a godsend. A man who is too avaricious, and a woman who is short of temper, can never live a good life, remember. Avarice will bring you down.’ Baba’s curses, verbal whiplashes—he is used to that. He is also aware that all the anger and frustration were a manifestation of the love Ranoji had for his youngest child—love that he did not know to demonstrate any other way. But Baba has a point. It is a crazy thought. Irresponsible, in fact.

But Raj Bahadur has faith…and a plan, ‘You don’t go there like a beggar, of course. You have to equip yourself for the job, you fool. Like a doctor or an engineer gets equipped to face their professions. Don’t you know that there is a new institute in Madras for film studies, acting, and other skills concerning cinema? You join the institute, get the training. Famous directors come there as guest lecturers. It is up to you to create a good impression. I have no doubts about your ability. They will notice you and give you a role.’ That was ingenious. Raj Bahadur was smart, a man of the world. Above all, he was a good friend.

This was perhaps too good to be true. But Bahadur didn’t indulge in idle words, he was a man of action. He got the application form and made Shivaji fill it up and even paid for the photographs that were needed to be attached to the form. Though the Kannada film industry was thriving, Madras was the epicentre for the South Indian film industry—even Hindi film producers and directors came there for technical assistance, sometimes. Shivaji was filled with doubts and apprehensions about the logistics. It was a two-year course—how was he going to pay the fees? And what would happen to his job? Raj Bahadur knew that was worrying Shivaji. He advised him to take casual leave from BTS, and then take leave without pay once the days of the casual leave were used up. That way he could hang onto the government job in case the plan to enter the world of cinema didn’t work.

Shivaji felt humbled by this turn of events. The steadfast love and generosity of Raj Bahadur, the magnanimous gesture of his brother—because of his stay in Madras the family may have to forego a meal daily—does he deserve all this? When he left for Madras, their encouraging words and hugs brought tears to his eyes. When he fell at his father’s feet, Ranoji mumbled, ‘Be blessed wherever you go. Let the gods be with you.’ Shivaji set off for this new world with hope and trepidation. Strange people. An unknown language. It was like plunging headlong into a dark tunnel.

This has been reproduced from the book Rajnikanth: A Life.

The banner image did not appear with the original publication and may not be reproduced without permission.

Tags

About the Author

Vaasanthi is a renowned author and journalist who writes in English and Tamil. She has been writing in Tamil for more than forty years and has published thirty novels, six short-story collections, four volumes of journalistic articles, and four travelogues. Her books in English include Cut-outs, Caste and Cine Stars: The World of Tamil Politics, Amma: Jayalalithaa's Journey from Movie Star to Political Queen, The Lone Empress: A Portrait of Jayalalithaa, and Karunanidhi: The Definitive Biography. She was the Editor of the Tamil edition of India Today for nearly ten years in Chennai. She now works as a freelance writer and journalist and lives in Delhi.

.jpg)