In any country that produces a relatively large number of films, the average production is more likely to be poor than otherwise. This is for the simple reason that a good film presupposes a measure of talent on the part of its makers, and talent happens to be a rare commodity at all times, in all the arts.

The average standard of films in India is, I believe, neither higher nor lower than, say, that in Japan, whose best films are, as we know, among the best anywhere.

The trouble with films from an artistic point of view is that while the laws of economics demand and create growth in the supply of films as a commodity, they do not at the same time ensure growth in the supply of gifted film-makers, which is conditioned by quite other factors.

More than those who pay to see them, I feel it is the people who make the films who are really responsible for their low average quality. Since the public is known, at various times, have taken to all kinds of films, good, bad and indifferent, it follows that if there were more good films than bad, the situation from an economic point of view would remain virtually unchanged. And, after all, there's never been a proclamation from the public that it is bad films they want and not good ones!

When I say good films, I don't exclude films made primarily for entertainment, provided they are made well and with good taste. The entertainment film is a separate and essential category which may or may not include films made by the true artist whose first concern, surely is to satisfy a creative urge. In this he is an artist like any other artist in any other creative medium. But as a general rule even the most serious film-makers, from Chaplin downwards, take into consideration the aspect of mass consumption, in their choice of subject as well as in its treatment. If they should choose to ignore this aspect and decide to make a highbrow film-a perfectly legitimate choice-they should also be prepared for smaller returns and plan their budget accordingly.

When a serious film-maker plans a film for wide consumption and it fails at the box-office, he will very probably discover and-if he is honest-admit, that the fault lies in a large measure with the film and not with the public. If he is objective enough about his own work, he may even spot the mistakes and learn a useful lesson from them.

The only way to find out whether public taste has deteriorated or not is to offer the public a larger proportion of wholesome film fare over a period of time and gauge the reactions. Since this is a hypothetical situation, it is pointless to dwell on it.

Personally, I strongly believe that a true revolution in the standards of film-making would find a public ready and eager to welcome it with open arms.

The largest responsibility lies, however, with the established directors who have a continuing opportunity to make films and the ability to make them well.

You cannot really reprehend mediocrity; you can only regret it. But you can and must condemn the gifted film-maker who has it in him to combine artistic integrity with a consciousness of dual responsibility to the viewing public and to the man who backs him, but who yet keeps postponing the great film because he must "first make a little money" and therefore must compromise "just this little, just this one".

This is a reproduced article from the book Film Industry of India.

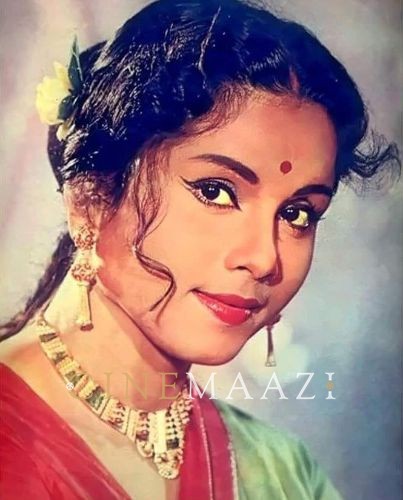

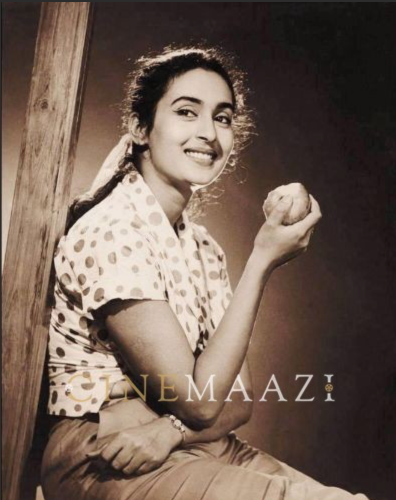

The image used is taken from Cinemaazi archive and is not part of the original article.

This section is for paid subscribers only. Our subscription is only $3700/- for one full year.

You get unlimited access to all paid section and features on the website with this subscription.

.jpg)