Khuda, Maut aur Ghulam... Guru Dutt

Subscribe to read full article

This section is for paid subscribers only. Our subscription is only $37/- for one full year.

You get unlimited access to all paid section and features on the website with this subscription.

Not ready for a full subscription?

You can access this article for $2, and have it saved to your account for one year.

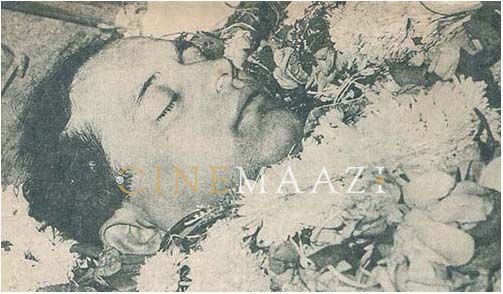

The big hall in the flat at Ark Royal, Pedder Road, was normally used as a living-room. But now the furniture had been removed, and it overflowed with people. Immaculately dressed in a steel-blue suit, blue tie and blue socks, he lay on the floor as if asleep. As if after a long hard journey, exhausted, he hadn't had strength to go to the bedroom and had lain down where first he could. And the anguish of all present was hushed too, as if they did not wish to awaken him.

The smoke of incense hung in the air and in the wall-mirror everything looked hazy, the men moving like ghosts. Then Raj Kapoor, his face bathed in tears, gently laid the last floral wreath. The bier was ready. The sob and cries rose to a heart-rending pitch. Someone said it was time to leave. A few hands stretched towards the bier, but Raj Kapoor gestured "no." Then turning with folded hand towards the women mourners, including the mother and the wife, he asked: "Do we have your permission?" There were only a few more sobs in reply. Shahid Lateef, Johnny Walker's cousin and two others lifted the bier. Rose chants of "Ram Nam Satya Hai," "Gopal Nam Satya Hai" Guru Dutt was on his last journey on Saturday, October 10, 1964.

It also symbolised the end of a journey which began on July 9, 1925. In his short life-lasting only 39 years - the Journey had been eventful. Guru was born at Bangalore, and brought up at Calcutta where he matriculated. He had a brief romance with journalism. But the zig-zagging road of destiny led him to Almora. He joined Uday Shankar's Art Academy (contrary to popular myth, Guru was never in Santiniketan, but studied mostly at a university with a much tougher curriculum - life itself), interested himself for a while in the classes that Shankar held in general education, stage technique, music, painting and "improvisation" (a fascinating ritual of jotting down mental images to the stimulus of a painting or a snatch of music). His family had migrated to Bombay and he himself proceeded to Poona to join Prabhat where an uncle, a commercial artist, was executing assignments from film production companies. The world of movies beckoned him.

He started as an actor. Reluctant, lean and awkward in his fussy costume, he appeared in Vishram Bedekar's "Lakha Rani." When he acted again, it was years later in his own production "Baaz" (1953). There at Prabhat a friendship ripened between Guru and another shy, handsome young man called Dev Anand. They came to room together, walking often to work, occasionally "doing" picturesque old Poona town on hired cycles. But professional life for the young apprentice was very hard. The old-timers at Prabhat were wary of letting ambitious young men learn their skills. Prabhat, too, (Shantaram had already left and the studio was beginning to crack up) was a citadel smug in its own self-righteousness, hostile to criticism. Guru eventually quit Prabhat, re-joined, at Famous Pictures, Bombay, Baburao Pai, the man who had given him his break at Poona.

Guru subsequently worked with such filmmakers as P L Santoshi and Gyan Mukherjee (a framed photograph of the late Mr. Mukerji hangs in Guru's business office today). When he directed "Baazi" for Dev Anand in 1950, Guru's real career began. "Baazi" was followed by another directorial assignment in "Jaal". In 1952, on little cash and plenty of hope, Guru launched "Baaz", and later Guru Dutt's company made "Aar Paar" (1954) following it down the years with the generally successful and occasionally significant movies. "Mr. & Mrs. 55", (1955) "C.I.D." (1956), "Pyaasa" (1957), "Kaagaz Ke Phool" (1959) "Chaudhvin Ka Chand" (1960) and "Sahib Bibi Aur Ghulam" (1962).

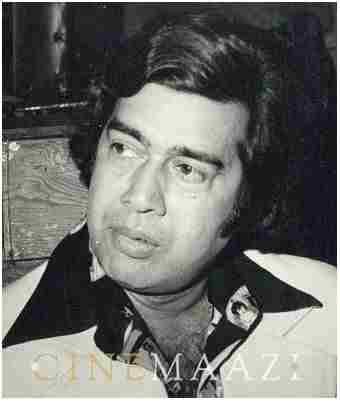

The clue to the success of the movie maker lay in the man himself. It is very difficult to talk about Guru Dutt, the man, though one could say a lot about Guru Dutt the movie-maker. One could never really get to know Guru Dutt. Like "most of us he flew into a rage, laughed, spoke tersely, loved and disliked but, even in his most candid moments he withheld quite a lot. The storm "within" filtering through his aesthetics to his sophisticated lips was dampened to just a gesture, a sentence, a nod of approval. For a fleeting moment he would lift the shutters - only for a fleeting moment could one peep into his soul. He never talked or behaved like the usual film men. He saw, thought and felt much more than the usual film men. His sophistication was more secretive than expressive. Its only outlet was films.

Although he came to films as an actor, he was essentially a director; he was a man who had something to say. Film is the director's medium. His contribution to acting is incidental. It started with an incident, a revolt against the star system of which, later, he became a part. In his portrayals of characters, he showed the same sense of timing mastery over emotions which he showed as a director. The greatness and promise of Guru Dutt do not mainly lie in the films he has made or his portrayals on the screen. They lie in his devotion to and understanding of the medium. In the chaotic world of films where people devote more time to propositions than purposes - he was one of the few who spent restless nights seeing images take on the continuity of life itself. He lent direction and a sense of purpose to film making by elevating the medium to a new aesthetic and cultural level. His appreciative eye picked talent for all departments of film making - writers (Abrar Alvi), artistes (Waheeda Rehman, Johnny Walker), and technicians (Murthy).

His films had the sterling quality of feeling and the gift of communication. His poetry of vision revealed a personality that was extremely sensitive to beauty. His images followed a rhythmic pattern. That is why he had no peer in the filming of song sequences. The women in his films glowed with a kind of spiritual beauty. Even the suggestion of a kiss was never quite the same as in other films - it was more a communion of souls than a physical experience. Guru Dutt was Indian to the core.

The films Guru Dutt did not make tell as much about him as the ones he did. At various times he started and stopped "Raaz" (a mystery story), "Gowri" (which - and not "Kagaz Ke Phool" - would have been India's first CinemaScope film), an Arabian Nights fantasy in colour, a Bengali film. He considered filming a Malayalam novel and a Tamil legend but later changed his mind. When he did start a film, it was not quite impulsively. But eventually some element of incongruity in the plot or his tentative approach to it would obviously stare accusingly at him, and he would give up. Guru Dutt was a perfectionist.

On the sets, the seemingly polite, dreamyeyed, mild-mannered intellectual could turn into a tyrant, almost impossible to please, and relentlessly driving himself and others always to do a little better.

Paradoxically, this movie-maker was at once ahead of most of his contemporaries (in his personal idiom, in the films he made) and a throwback to a generation now gone, of hardy pioneers who led a team rather than went along with it, who preferred to formulate their own convictions and difficult decisions, to shape their own destinies. Guru was rather like the sea captains of old, who were absolute bosses on the high seas, setting their own compass, steering their own course. He was no front office executive, guided by computers, human and mechanical. In his moods of insularity, vacillation and stubbornness, there was something child-like in him.

He was an authentic loner of our times. He talked little, least of all about himself. There was something about him which discouraged interviewers seeking the minutiae on which star images are built. His smile meant not that the draw-bridge across the dividing moat would be let down but that it would continue to stay up. Engaged in a trade where communication, folksiness, slaps-on-the-back, hail-fellow-well-met and boisterousness, real or simulated, are the glib currency, Guru Dutt lived mostly in his private gazebo, an ivory tower. It is a comment, partly ironic and partly happy, that the business put him generally in a position of being able to afford the ivory.

He had his faults. He could have disciplined his tensions but possibly the process of discipline would have killed something of his genius. The best comment on the event of his death came from a writer who had worked with him for many years. "What a waste of life!" the writer moaned. All in all, he was a lovable man. He was Guru Dutt.

The last time we saw him was on the sets of "Baharen Phir Bhi Aayengi" (1966) two days before he died. He was playing a reporter in the film. He resigns from his job and, in the shot we saw, he throws his resignation letter on the table and tells Mala Sinha, "Whether you accept it or not, this is my resignation. I am going..." Mala tries to call him back. But he doesn't return. Now he won't return, ever.

We went to his office upstairs. He told us that he wanted to come and see the working of our editorial offices. He wanted to take some shots there. We told him he was welcome any time. Perhaps next week, he said. He never kept that appointment. But that was not the only appointment he did not live to keep. On Friday night at 12.30 he spoke to Raj Kapoor on his neighbour's telephone. They exchanged views on the recently formed Actors' Guild of which Guru Dutt was a founder member. He invited Raj to come over on Saturday evening. He had also arranged to show him his "Kaagaz Ke Phool'' (1959).

After his conversation with Raj he went into the drawing-room where. Abrar Alvi was writing the cimactic scene of "Baharen Phir Bhi Aayengi" (1966). Ironically, it was the death scene of the character Mala Sinha plays in the film - one that involved loneliness, mental derangement and a heart attack. His reaction to the scene was that of a normal man. While discussing the scene, he told Abrar about a letter he had received from a friend who was in a lunatic asylum, recalling that Guru and he used to go to the New Lucky Restaurant in Poona about 18 years ago. The man had written after such a long time and had asked for financial assistance. Guru had observed that the writer seemed not very sure about getting the assistance and had therefore written and cancelled a number of addresses to which the money might be remit ted. He had also observed that there was nothing in the text of the letter itself to suggest that the man was mad. There was also some discussion about the "loneliness" involved in the "scene"Abrar was writing.

Both Raj and Dev Anand were among the first ones who were told over the phone of Guru's death. Dev cancelled his shooting and rushed to Pedder Road. Raj too came and accompanied the body to the Coroner's office. After the post-mortem and other formalities were over, the body was brought back to Pedder Road.

Sunil Dutt and Nargis were also among those who paid their last respects. Two days after the death, Nargis said, "Geeta told me that she felt very restless on Friday night." According to Nargis, Geeta residing then at her mother's house had a strange premonition. So much so that at 11 o'clock she wanted to go to Pedder Road, but couldn't because there was no car. Her mother didn't like the idea of her going at such a late hour. Besides, it was pointed out to her that Guru was supposed to go away next morning to Madras. She retired to bed but couldn't sleep. At about 2 a.m., for no apparent reason, she felt extremely uneasy. The first thing next morning she rang up Guru Dutt. The telephone is in a neighbour's house. When Guru's servant came on the line, she asked him to wake up her husband. The servant went away and then came back to say that Guru was still asleep and the bedroom door was locked. Geeta then asked the servant to break open the door. She then took a taxi and went to Pedder Road from Bandra with her one-year-old daughter.

"Poor Geeta," said Nargis, "she was crying so much I just couldn't bear to look at her very long."

Meanwhile, the news of Guru's death had spread like wild fire in the city. By 5 p.m. all the known and lesser known personalities of the film industry gathered outside Guru's house. Since the death was sudden and unexpected very few came to know about it in the beginning and some even refused to believe it. The industry reeled under the impact of the shock as the news was confirmed. In a short time people were contacted over the telephone. Meena Kumari was shooting at Roop Tara Studios on the sets of "Bahu Begum" (1967) when she was given the tragic news by Sadiq Babu. At Modern Studios, Prithviraj got his producer to pack up. All studios stopped working.

People came one by one as the tragic news reached them. Even then there was a large number of Guru's friends waiting out side, standing on the staircases and inside Guru's flat. At about seven o'clock, Waheeda Rehman came with tears in her eyes. Then came Meena Kumari crying. Then Sohrab Modi and others.

As the bier reached the door, Geeta rushed behind it, sobbing and crying. Meena Kumari caught hold of her and held her in a comforting embrace. Waheeda Rehman stood sobbing. Also her sister Sayeeda. Slowly and gently they carried the bier outside the building. The lorry in which the body was to be carried was waiting. The bier was placed on it and hundreds of wreaths and floral tributes were placed over the body as the lorry, which belongs to Guru Dutt Private Ltd., moaned, chugged and began crawling towards Sonapur carrying its master still surrounded by his colleagues, members of his unit, friends and fans. Some were standing or crouching near the bier, a large number were walking on all sides of the lorry. Johnny Walker held Guru's sobbing brother Atma and patted him on the back to console him. Among those who had gone to Sonapur ahead of the funeral procession were Shammi Kapoor, Johnny Walker, K Asif, Jaimani Devan, Kamal Amrohi and others.

K Asif, who had been allowed to go home from hospital, only a day earlier, was advised not to exert himself. When his friends tried to prevent him from going to Sonapur, he did not listen to them. "I won't be able to sleep if I don't see his face," he said. "I must go and see his face for the last time." He sat on a bench with his right arm in a sling.

Johnny Walker and Waheeda had gone to Madras the same day in connection with a cultural programme. No sooner had they checked in at the hotel in Madras, than Johnny received a trunk-call from Bombay. By chance the trunk-call matured within seven minutes of its booking which gave them the chance of returning by the evening flight to Bombay. By 8 p.m. the crowd waiting outside the cremation ground became very large. The police arrived with the funeral procession at 8-30 p.m. There was a stampede as the body was carried to the pyre. One could see nothing but people rushing and being pushed back by the police.

Dev Anand, Raj and Shammi Kapoor requested the people to stay behind. But the people - producers, directors, actors and fans - surged forward to have a last look.

Shammi Kapoor went up to K Asif who was still sitting on the bench. He helped Asif through the crowd and brought him where Guru's body lay and the last rites were being performed. Asif bent down and gently and lovingly held Guru Dutt's cheeks for a few moments in his left hand, then stood up and said to Raj: "How innocent he looks... as if he were only asleep."

Meanwhile the religious rites continued, and the pyre was being prepared. Members of Guru Dutt's unit brought wood and began splitting it. People thronged, pushed forward to see Guru Dutt for the last time and were being pushed back by the cordon round the dead body.

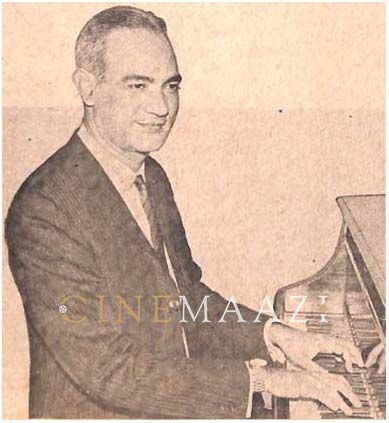

O P Nayyar was telling some people that Guru had asked him over for a sitting on Sunday. He had composed a new tune for "Baharen Phir Bhi Aayengi" and Guru wanted to hear it.

Someone observed that Asif's "Love and God" would get stuck. Guru was playing Majnu in it. "I have lost a great friend. And that is my only loss," said Asif.

Subodh Mukherjee said he was a fan of Guru. He had always thought that Guru was one of the most distinguished film-makers. " 'You make such beautiful films,' used to tell him. 'My only complaint is that you make so few. Why don't you make more?' "

It was then that Atma Ram set fire to the pyre - the fire that purifies.

The chanting grew in volume. The Lord's name is Truth. The flames rose hungrily. Truth is Eternity. The flames leapt up. And Eternity reclaimed one of its priceless moments. And still the flames leapt wildly. Eternity emancipated the slave of Time from the chains of Destiny, of Death, forever.

This article was published in 'Filmfare' magazine's 30 October 1964 edition.

The images are taken from the original article.

.jpg)