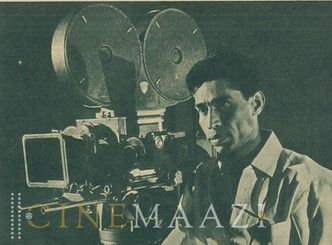

His Director's Eyes: The Legendary V K Murthy

Introduction by Shantanu Ray Chaudhuri

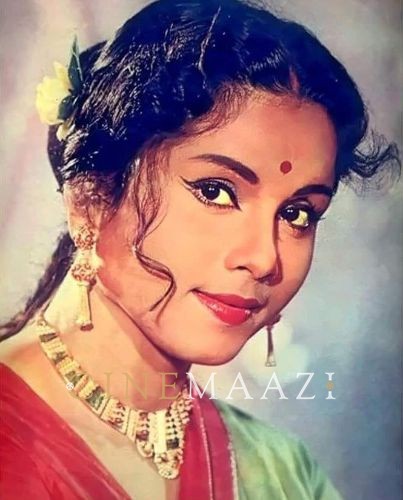

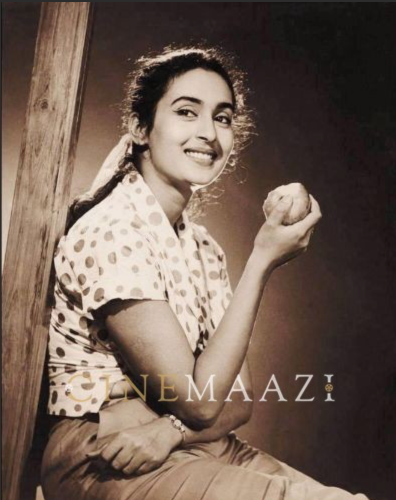

Though he was truly captain of his ship, looking into every aspect of film-making through most of the films his banner produced, Guru Dutt leaned on his team to provide support, and at times a counterpoint to his views. If Abrar Alvi was his sounding board and alter ego, credited with creating the framework of screenplay and dialogues that the master director clothed with his unique vision, V.K. Murthy was his visual counterpart. Much of the brooding climate that prevails in the films of Guru Dutt owes its mood to Murthy’s sensitive camerawork and painstaking shot-taking.

Most cineastes focus primarily on their later collaborations – which isn’t surprising given that we are talking of Pyaasa (1957), Kagaz ke Phool (1959) and Sahib Bibi Aur Ghulam (1962), each a lesson in lighting and cinematography. However, Murthy’s earlier films too provide a glimpse of his keen eye and visual skills.

Guru Dutt is said to have noticed Murthy during the shooting of Navketan’s Baazi (1951), Dutt’s maiden directorial venture. The cinematographer on the film was V. Ratra and Murthy was an assistant. The fluidity and flow that Murthy managed in a particular shot – a pan from a reflection in the mirror to Dev Anand to Geeta Bali and the chorus rendering ‘Suno gazar kya gaye’ – impressed Dutt enough to take him on for Jaal (1952). Dutt would never use any other cinematographer again, even on projects he produced, like 12 O’ Clock, directed by Pramod Chakravorty, or CID, which Raj Khosla directed.

Guru Dutt’s vision often involved a number of dynamics at play at the same time – trolley movements, pans, intricate angles – and it is to Murthy’s credit that he delivered without fail. This in an era largely marked by flat camerawork with little visual dynamism. No wonder he came to be known as Guru Dutt’s eyes. He was a master at creating the chiaroscuro effect, which marked Dutt’s early noir ventures such as Jaal and Aar Paar.

Murthy found himself at a loose end after Guru Dutt’s death, working mainly with Dutt’s one-time assistant Pramod Chakravorty. None of these films had the vision that marked his collaboration with Dutt and the only project of note he worked on post Sahib Bibi aur Ghulam was Shyam Benegal’s TV serial Bharat Ek Khoj.

In the eloquent section that follows, excerpted from Ten Years with Guru Dutt: Abrar Alvi’s Journey, Abrar Alvi talks about the legendary song ‘Waqt ne Kiya’, the lighting and shot-taking of which has become part of cinematic legend. Abrar Alvi often refers to the fact that Murthy would take a very long time to set up the lighting for a shot, a cause for great heartburn between Dutt and Murthy, at times leading Dutt to leave the sets in a huff. If Alvi sounds dismissive of Murthy as someone more immersed in his work and lacking in social skills, he is fulsome in his praise of the cinematographer when it comes to his lighting expertise.

[The following is an excerpt from Sathya Saran's Ten Years with Guru Dutt: Abrar Alvi’s Journey published by Penguin India.]

Guru Dutt decided every shot of the films he directed. He would place the camera, work out the shot. Choose how close he should go for a close-up; very little was left to the cameraman to decide.

If ‘Waqt ne kiya’ is still considered one of the best song picturizations in India cinema, there is a reason. Some techniques that Guru Dutt followed in shooting that song had never been used before. Yet today, many of those techniques have almost become passé, thanks to indiscriminate use.

For one, the lighting was dramatic, and in tune with much of the visual effects created by the use of light in the film’s many striking moments. It is common knowledge now how the shaft of lights that cuts diagonally through the frame was created by placing a mirror at angle in the skylight that the studio set was fortune to have, but at that moment, while we were creating the scene, it was cause for much sweat, agony and finally, excitement. We tried every trick and technique to get the impact Guru Dutt wanted, and eventually it worked. And so wonderfully well.

We first used a 1000 kW light, but it was not enough to create of beam of the intensity the director wanted. Finally we had to think of some other source of light, as artificial light was clearly not going to work. The solution: get the afternoon sun into the studio.

Kaagaz Ke Phool was being shot in Mehboob Studio, where we knew the studio inside out. It was a modern studio with a sloping roof, a terrace above it and a skylight. Guru Dutt got a huge mirror and two or three smaller ones made in order to create a never-before lighting effect for his song. He suggested the mirrors be so placed that the largest one, on the terrace, would deflect the sunlight on to the smaller ones which, acting like reflectors, would send the beam of light into studio through the skylight. It was masterly.

I learnt a lot about lighting from him. It came in handy while directing Sahib Bibi Aur Ghulam. But I could never really rise to his standard of using light in a scene to make it unique and painterly.

Even more unusual was the fact that for the first time a song was shot that explore the emotional mood of the protagonists. There had been songs that were played in the background, third party songs so to speak, where the lyrics either spoke to or about the actor or actress on screen and these were usually filmed in long shots. Guru Dutt took the idea one step further. He had the two protagonists voicing their emotions as if subconsciously without moving their lips. Expounding the personal feeling of both character without them actually moving their lips was something absolutely fresh and new at that times.

Tags

About the Author

Best known for her long association with Femina, which she edited for 12 years, Sathya Saran is also the author of a diverse variety of books. The Dark Side reflects her love of the short story, while the critically acclaimed biographies, 10 Years with Guru Dutt: Abrar Alvi's Journey; Sun Mere Bandhu Re: The Musical World of S.D. Burman and Baat Niklegi Toh Phir: The Life and Music of Jagjit Singh bear testimony to her love of cinema and music.

Sathya has just completed a biography of Pt Hariprasad Chaurasia. Till recently Consulting Editor of Harper Collins India Pvt Ltd., her assignments included editing the newly-released anthology on marriage Knot for Keeps.

Sathya teaches fashion journalism at NIFT Mumbai, Kangra and Srinagar. She has been a stage actor with Veenapani Chawla. Passionate about writing, she recently held the first of its kind Writers Conclave titled The Spaces Between Words, the festival sponsored by JSW, in partnership with The Hindu, at Kaladham near Hampi.

Sathya has written a television serial titled Kashmakash on marital problems.

Her column in Femina and Me magazine is now continuing to gain new fans as a guest column in Dainik Jagran.

.jpg)