Film Criticism: Then and Now

When I first started writing film critiques for the Statesman, Mr James Kewley-Cowley, the editor said to me: ‘You will be paid Rs3 per inch, admittedly not a very elegant way to measure literary output, but there it is.’ Mr. Brook, the news editor, clarified things further: ‘I shall tell you many inches per review according to the advertisement we get from different cinemas every week. This week The Odeon has given them eight inches. Add to this the fact even up to 1991, there are no regular previews of films in the capital of India, and you will not wonder that I took up film reviewing very reluctantly.

But then, I had been dragged into it by a very discerning journalist called R.P. Nayyar, who ran the Indian PUNCH, Shankar’s Weekly, practically single-handed while Mr Shankar Pillai, the editor and the doyen of Indian cartoonists, was sending shivers through politicians and being asked for autographed originals of his cartoons by British Viceroys. As we strolled down marine Drive one evening admiring the sun setting over the Arabian Sea, RP suddenly stopped in his tracks and said out of the blue: ‘Why don’t you review film for us? Here you are, right in Bombay, the home of the desi film industry, what more can you want?’

‘What? Watch those stars making sheep’s eyes at each other as they chase each round a tree while someone else dubs their songs? You must be out of your mind.’ ‘I am not’, persisted RP. ‘It is a sociological worth serious in-depth study. Why do millions of Indians go to the cinema, why is it the most popular medium of mass entertainment?’ A good question, or two good questions, to be precise. So that is how it started and I have not regretted it. And to sum up my experience in one sentence, I would choose the title of that old song: ‘It’s foolish, but it’s fun.’

But the most important question remains: Does film criticism make any difference to the cinema in India? And who reads reviews anyway? Well, considering the majority of Indian still cannot read and write, and considering newspapers and magazines are still largely an urban phenomenon, I feel it does not make an iota of difference, to the average commercial film what elite writers say about them in elite papers. And the wise elite writers do best when he analyses these films, just as R.P. Nayyar wisely said all those years ago, as the social phenomenon or the social index they constitute with all their trapping: The star system, the song and dance adjuncts, the small fee paid to the director as compared with the leading lady, and so on.

It is a different matter that audiences are also interested in the hairstyles, the way of life, the latest scandal, the fascinating professional intrigues, of the film world. That is human nature and well looked after by saying, the fan magazines of South India, the more stylishly sophisticated but equally crude stories carried in some Bombay glossies, that sometimes lead to libel suits hugely enjoyed by all. Equally important to the industry, which thrives on stories about going-on of their stars, are the trade journals, which provide forecasts about the fate of films about to be released or in the making, complete with their own intrigues and side shows. Some of them, of course, are highly professional and matter-of-fact publications and also have their place in the sun. But it is the gossip papers which have the largest circulations and one need not even explain why.

What, then, is the place of serious writing, or what one must label, for want of a better description, elite criticism in the elite papers? After all, we in one way or another, consider ourselves students of the cinema and are not necessarily either professor of the cinema or godfathers of the cinema.

Apart from that bit about the sociological assessment of the rank commercial films-and, one must not imagine for a moment that there is no horse sense or merit of any sort in them-there is the fabulous technical advance made by Indian cinematographers, the at times breathtaking sweep of the photograph, the elegance of the colour, the magnificence of the sound. And, yes, the sheer professionalism of the directions, the actors, the actresses, the showmanship, the unerring finger on the pulse of the audience. There is a good deal of crassness, of exploitation, of sheer waste and selfishness. But, like the folk performers of old, and the Indian cinema is still the most modern and most popular folk art in India, there must be something to it to have survived in the middle of the onslaughts of televisions, which it has invaded in a big way by not only providing Doordarshan with its biggest audiences but with the makers of its most popular serials, invariably made by Bombay’s movie moguls. In spite of the advent of video cassettes and video parlours, complete with blue films, the Indian cinema is still alive and kicking.

But, most importantly, it is the serious writer on cinema in India who has kept the film societies up-date on what is happening abroad. In a highly literate state like Kerala, the serious filmmaker would not have reached today’s heights if someone had not been there gently and at times fiercely pointing out just what was so good, or so different about Malayalam films local, not only in little villages where films are taken seriously but in other parts of Indian and the world.

There has been a pleasing internationalism in Indian film writing which has also infected the foreign film writer who visits India during films weeks and films festivals. If Indian films buffs are well up on Jancso or Olivera or Tarkovsky or Fassbinder or Truffaut, it is because they have been written about in the elite papers and quite often with individualism and maturity. Every Indian film daily and Sunday magazine worth the name has, particularly in recent years, and film writers have gone into their social, professional and at times political nuances with a high degree of discernment and sometimes even anticipation.

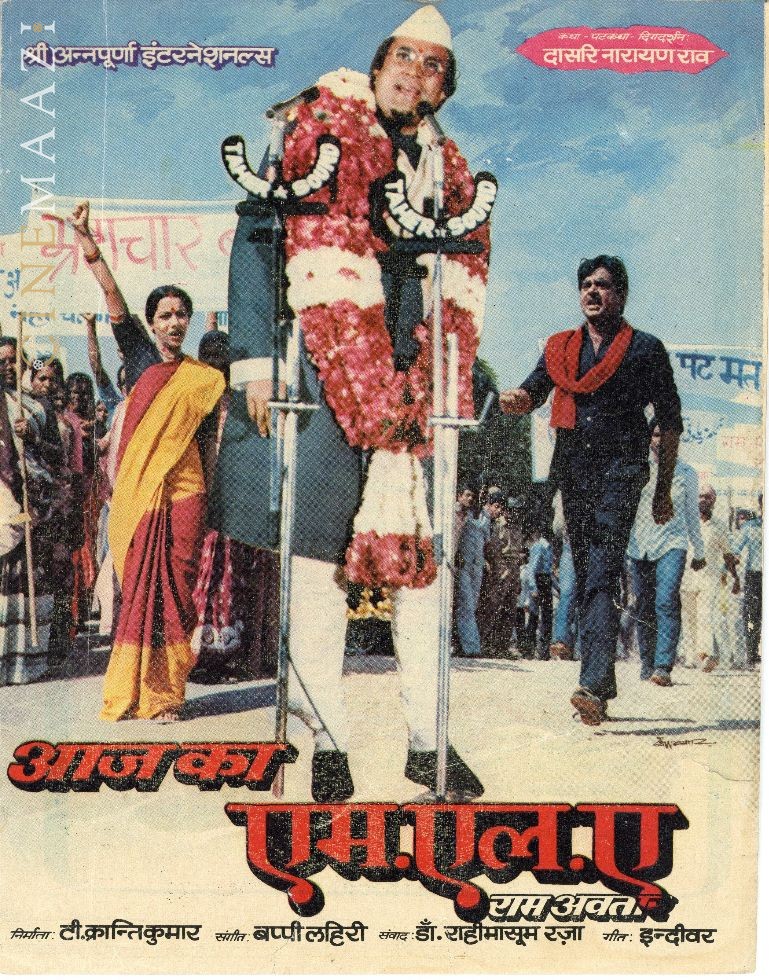

It was a film writer who first noticed the almost subliminal political messages creeping into Tamil films when political films per se were not possible to make. Canny audiences knew exactly what the rising sun or a red sofa set stood for. It was not a very far cry from that to film stars coming from the cinema to politics and providing at least three chief ministers of states, not to speak of innumerable MP’s and MLA’s (there is actually a film called Aaj Ka MLA, among others and one of the stars was to run for MP in the Course of a few years). Again, it was the job of the film writer to spot these trends, of politicizations of the cinema, as much as it was that of writers on politics. Right up to date, the debate about Amitabh Bachchan’s brief and a disastrous excursion into politics is as much the concern of the writer of film as his counterpart in political writing.

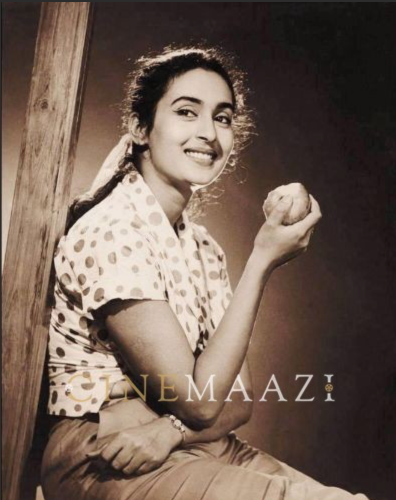

However, if the place of the Indian film writer is to be assessed at its best, it is what Indian film criticism has done in discovering talent, spotting significant new trends in regional and national terms and above all, in building up off-beat filmmakers and films which later went on to become internationally famous. When Satyajit Ray was pawning his wife’s jewellery to raise funds for making Pather Panchali (1955), there were certainly Indian film writers around who gave him sympathetic support and publicity. When actor Motilal made a modest small-budget film which hardly stood a chance at the box-office, it was discerning writers who recognized its courage, wrote it up and it went on to win the president’s Gold Medal against heavy odds. Most of the off-beat film directors, actors and actresses who emerged in the seventies in India, would not have stood where they are today had they not been given something of a head-start by early talent spotters from the Indian film press.

In that sense, writers on films have more than stood by the Indian cinema as well as foreign cinemas in their writings. And that is no small contribution to what can be described as the considerable films sense and the admirable standards which by and large, the Indian film press has observed down the years.

This is an archival reproduction of the article.

Tags

About the Author

Amita Malik is known as The First Lady of Indian Media she started her career in All India radio. Her popularity rose when she started writing the popular column Film Notebook in The Statesman. She can be credited for laying the foundation of serious film and media studies and criticism in India.

.jpg)