Early Filmmaking in Calcutta

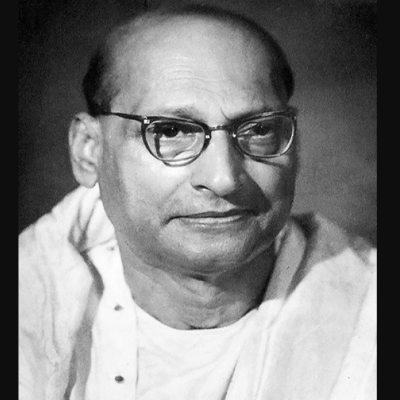

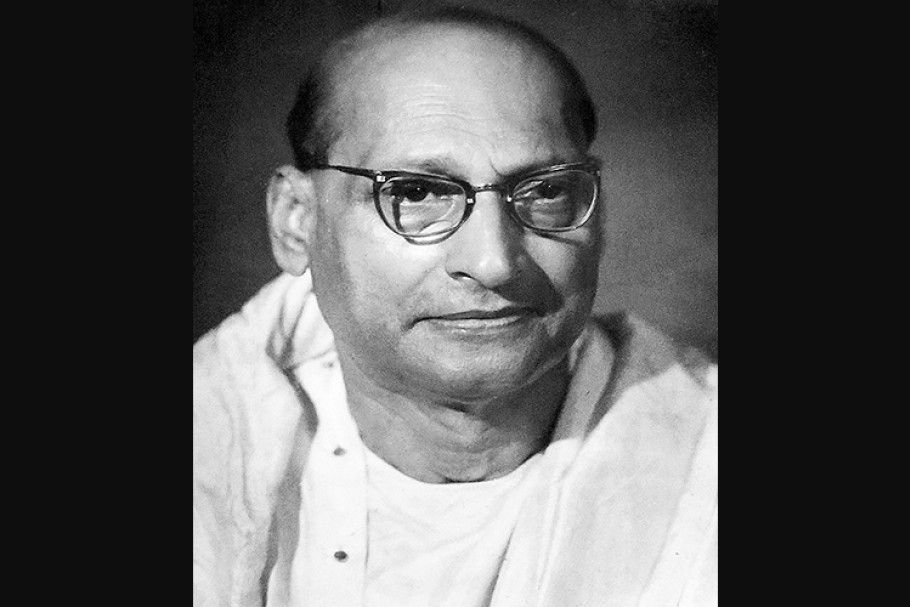

The peerless stage and screen veteran of Bengal, Ahindra Chaudhuri, narrates in this article written in a strongly reminiscent mood, all the interesting experiences of his career full of years and honours, relating to the switch-over of the Bengali screen from the ‘Silver Silent’ to the Golden Taking Age.

Cinematography as an industry is making rapid strides today even in this country and we are indeed passing through a boom period in the trade. On a close scrutiny, one will be astonished to see that on an average sixty Bengali Films or so are produced every year and there are nearly ten film studios in and around Calcutta. Hundreds of picture houses have been erected in and around the city most of which are having a boom time. Some of these houses are as luxurious as could be desired and many are air-conditioned too. Statistics will indicate that millions of rupees are undoubtedly employed in the industry and thousands of people are making their bread from allied branches of the trade such as picture making, distribution and exhibition of films.

The art of film making has developed tremendously and this might well be called colossal. We and a few of us, who are old fossils and are not being content with a place in the gallery of natural history are still plodding wearily along the memory-lane of the filmland-our mind goes back almost thirty-five years back to a period which will appear to many as dark and crude, when there could not be found anywhere in this vast city such high walled, asbestos-covered, godown-like building electrically equipped with high voltage intensity which goes by the name of a film-studio today.

Film-making was not unknown then and films were even then produced in studios, but not like the ones which all of us see today. There were only two or three Studios with wooden platforms to hold adjustable screens for letting in and shutting off sunlight. This was laid in an open space in a garden house in the suburbs of Calcutta. A barrage of reflectors with pasted silver papers on a board served the purpose of high-powered incandescent lights. The studio at Behala, where we shot the Soul Of A Slave (1922), was then unique of its kind not only in Calcutta but anywhere in India. It evolved out of a model of “Ferndale” open-air studio conceived by William Fox. It was composed of two walls each twenty feet high, cross at right angles, thus making four sections. Each wall contained several open arches about 14'*18' and 12'*15' with a turntable at the top of the junction of walls for holding mirror reflectors. These were used for giving strong backlights. There also were some rows of silvered reflectors for modelling of the artistes. Besides, there were two towers, each three-storyed on east and west, accessible by inside ladder and fitted with mirror reflections which caught direct sunlight and in turn transferred the rays to the turntable reflector at the top of the walls. Shooting was done in open air but not on direct sunlight. We worked in shade, this side in the morning and in the afternoon, when the sun went in the western horizon, we worked in the opposite chamber in the plenty of the shade effected by the high wall.

As time advanced the industry began to settle down and people gradually grew cinema-minded. Producing companies made profuse money but there were no improvements in studio construction or technical excellence by using better class of machines. Madans, who were the pioneers and leaders of the industry in this country resolved to erect an all-weather studio covered by armoured glass plates and equipped with mercury vapour lamps. The floor was laid in solid concrete; iron structures were erected but it remained uncovered for want of reinforced armoured plate glasses, which had to be imported from foreign countries, as they were not available in Calcutta markets.

A revolving stage with complete outfit, intended for “The Bengali Theatrical Co.” then housed at Cornwallis Cinema, which was then ordered from England, came to Calcutta but no Theatrical Co. was working then at Cornwallis Cinema after the measurements’ of which it was ordered. Finding no other place for it-it was fitted there. Some lights also came from ‘Efa’s at Germany. They were also sent up to the blank stage of the Cornwallis theatre. Now how to use them? A bright idea came to Mr. Framji Madan, who at once ordered to use the Cornwallis Stage as a film studio in day time. I was then attached to the Madan’s Film Co. and we started the production of ‘Misser Rani’ (Mishar Rani, 1924), an adaption from Iraner Rani which was a high hit then at the Star Theatre. I appeared in my original stage role. We used to shoot scenes from 8 in the morning to 4 in the evening on weekdays, except on Saturday, Sunday, and public holidays, when Cinema shows started at 3-0 P.M.

The camera stood on a high platform on the aisle of the auditorium just in front of the stage. When any variation of shot angle was required, the workmen moved the revolving stage to bring the scene to its desired angle. Close-ups were mainly taken by the change of lens. Very seldom was the camera taken over on the stage. Thus we finished the production of ‘Misser Rani’ (Mishar Rani) but the experiment did not prove successful and so it was abandoned. Later on, these lights were stored in the Tiretta Bazar Godowns of the Madans and the unfortunate revolving stage was shifted to the Crown Cinema which was them building up. It was a well-equipped revolving stage, big, smooth-running and noiseless, but it served no purpose. What happened to it ultimately nobody knows; this was the fate of the first Revolving stage in India imported from abroad. It died unheard and unsung.

For another few years, the silent him went on developing and was on the point of blooming, when it was shattered by the new tornado of talkies. Then came Alam Ara (1931), the first Indian talkie from Bombay. But by that time Calcutta also introduced the talkie making machines. Machinery, and complete sets with technicians were imported by Madans from U.S.A. and Europe. Everything was there except a sound studio. We used to take short pieces of selected scenes from popular stage plays-as no readymade script was available. Nor did anyone know the technique of making one. So it was safe to select a good scene from one of the popular stage plays and have them acted by the well-known stage stars before the camera for four minutes or near about that, because although the equipment came there was no arrangement for bigger laboratory, studio or editing rooms which were then only being built up. Silent camera magazines used to hold 400 ft. films while the talkies used 1000 ft. roll; the laboratory equipment were all designed to suit silent films including the developing tank and rack, which was to hold only 400 ft.; so this required the shortening of the acted pieces. We did not feel the want of a studio because we had to go out for location somewhere in the Tollygunge and Russa Maidan, which were then a vast field of shrubs and trees and shallow ponds and used to shoot our scenes there. When some interior scenes were required the stage carpenter fixed it up on the concrete floor left uncovered for want of armoured glass panes, the set being shifted from Corinthian Theatre to Tollygunge by Madan’s motor lorries. They also got a bus for carrying artistes and these were fitted with mirrors and short shelves for make-up. Thus the shooting unit could go anywhere and shoot their scenes without making any elaborate pre-arrangement. This marked the beginning of the Talkie Era in Calcutta.

Within two decades the talkie reached its zenith and Bengal soon rose to a position of acclaimed eminence with the sober tone of the themes of her films and the simple and human execution of the same. Its films are acclaimed today in the foreign film festivals. This does not, however, signify that we have achieved perfection in our technique, Calcutta was once the greatest rival of Bombay and produced not only Bengali, Hindi, Urdu and Punjabi films but innumerable Tamil and Telugu ones, with occasional Assamese and Oriya pictures. Unfortunately, she is now dealing with Bengali films only and keeping herself abreast of the times by the sheer merit of her films and strong story value. She is, however, technically far behind others. Why? During the boom period of the Second World War, the Studio owners stopped their own production and hired out their studios for more certain and lucrative profits to the independent film producers who grew like mushroom in large numbers. These studios worked in both day and night shifts. Additional floor spaces were improvised, and all the reserved or stand by equipment worked continuously. Money poured into their pockets no doubt, but the machines soon wore out. Some of them were replaced and others were assembled locally form old materials, as no new thing could be obtained then. Orders were placed for other things not available in the local market, but they also arrived long after the war was over. Money which once poured in torrents now became scarce and thinned away. So some of the equipment ordered for was taken delivery of while others were left in the lurch. Thus some microphones came but not their ‘booms’ and so there remained the same old ones which had served for 20 years but were now rusty and noisy. New lanterns came but not their high-powered incandescent bulbs. Even some cameras came but their dollies and trollies were so pathetically worn out that they did not work electrically any more. Unless the whole machinery of our studios are changed lock stock and barrel it would be no wonder if the production business soon suffers tremendously. Those who are really concerned about the welfare of the trade, as far as it relates to West Bengal, must think deeply about the gloomy aspect of the picture. If one or two good pictures are occasionally produced here with a depiction of typical Bengali life in the midst of natural surroundings such as a thatched cottage in the midst of a bamboo grove in primaeval sylvan situations or the quivering ripples of a placid lily pond perturbed by drizzles or a Bengali brunette clad in a graceful sari taking her timid steps to the altar of her domestic deity at dawn and with such other lyric effects it cannot be rightly said that the art of production is yet anything like technically perfect here. Even strong story elements will not be able to maintain our high tradition for all time to come. It must end someday. We must think of that fateful hour from now on and prepare for warding it off.

In order to make our films technically perfect, our studios must be re-equipped and recast without delay. Bengali films are now being produced by Bombay with the help and assistance of Bengali artistes using well-adapted Bengali stories. The story and technical elements being almost flawless in these Bombay-produced pictures, imperfect Bengali productions cannot match with them. Such pictures are sure to win laurels in West Bengal and would sweep the market sooner unless we call a halt to them. All financial assistance should, therefore, be made to our studios to remodel them anew.

Are our financiers in a position to do it? If they do not come forward with their calculated foresight in the immediate future, the history of the Calcutta film studios will soon be a history of the past which will be read and remembered only by scholars of historical research in the study of film making only!

Cinemaazi thanks Sudarshan Talwar for sharing this rare interview published in Amrit Bazar Patrika.

Image credit: madantheatres.com

Tags

About the Author

.jpg)