Chalo Natak: The appeal and influence of Parsi theatre

Nichola Pais explores the Parsi theatre, a highly influential movement in the realm of modern Indian theatre, and its impact on cinema.

Indian theatre has ancient roots. Some scholars opine that it emerged in 15th century BC. Ancient Vedic texts like the Rigveda show proof of drama plays that were enacted during Yajna ceremonies. In medieval India, from the mid-12th century to the 18th century, India’s artistic identity was seen to be deeply rooted in its social, economic, cultural, and religious views. Performances including dance, music, and text were an expression of devotion for Indian culture. Adapting to the socio-cultural landscape of their patronage, by the early 13th century, a marked change had set in. Sanskrit dramas and stagecraft, which had been patronised by the elite, had become redundant owing to the influx of Turko-Persian influences. Modern Indian theatre can be said to have developed during the period of colonial rule under the British Empire, from the period between the mid-19th to the mid-20th century. Also known as Native theatre, modern Indian theatre denotes a theatrical approach which sees the Indian social space meeting with Western theatre formats and conventions. Modern Indian theatre took root in Bengal, where plays like Buro Shalikher Ghaare Roa (1860) by Michael Madhusudan Dutt, Nil Darpan (1858–59) by Girish Chandra Ghosh, and searing works by Dinabandhu Mitra and Rabindranath Tagore explored concepts of nationalism, identity, materialism and spiritualism. So widely did the power of theatre grow, that the British government in India went on to implement the Dramatic Performances Act in the year 1876 to police seditious Indian theatre, and curb the use of theatre as a tool of protest against the oppressive colonial rule.

What is Parsi theatre?

Success beckons

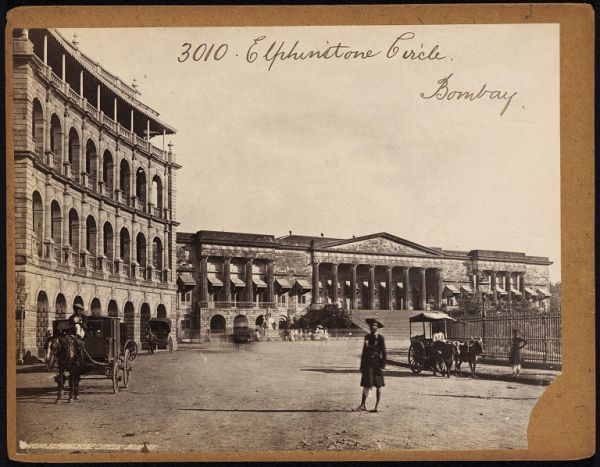

The history of Parsi theatre can be traced to the mid-19th century which was the time the British community in Bombay staged theatre in English. Parsi theatre derived inspiration from the English stage and it was in 1853, that they began staging their own Parsi-Gujarati plays in Bombay. The students of Elphinstone College in Bombay had apparently formed a dramatic society and started performing Shakespeare. Parsi Natak Mandali or Parsi Drama Company, the first Parsi theatre company, with Framjee Gustadjee Dalal (pen-name Falugus) as its proprietor, is said to have performed their first play Roostum Zabooli and Sohrab in 1853. This was followed by King Afrasiab, Rustom Pehlvan and Padsah Faredun. The very first performance of Parsi theatre in India is said to have taken place at Grant Road Theatre, Bombay. Incidentally, it was Grant Road Theatre along with Bombay Theatre, built in 1776 and modelled after London’s Drury Lane, which became popular for Parsi theatre performances. The Parsi Natak Company was supported by prominent Parsis including Dadabhai Naoroji, K.R. Cama, Dr Bhau Daji, Ardeshir Moos and others. Its popularity grew swiftly and by 1869, there were more than 20 Parsi theatre groups birthed in Bombay. Among the many theatre companies by the Parsis that emerged, were the Zoroastrian Theatrical Club, The Student Amateur Club, The Victoria Natak Mandali, Natak Uttejak Company, Empress Victoria Theatrical Company and The Alfred Natak Mandali. What began as amateur groups soon turned professional, as demand grew with audience numbers swelled by the city’s burgeoning middle class. An influential theatre tradition staged by Parsis and theatre companies largely-owned by the Parsi business community had developed. Hindustani, more specifically the Urdu dialect, was the language of performance with Gujarati also being popular. Debuting in Bombay, various travelling Parsi theatre companies proceeded to tour across India, especially north and western India comprising Gujarat and Maharashtra, popularising proscenium-style theatre in regional languages. Their repertoire included adaptations of English plays, Indian and Persian historical, mythological and social dramas. These plays not only entertained the masses but conveyed messages of social reform. Their popularity was immense, so much so that Parsi theatre even reached South East Asia, where it was known as Wyang Parsi and often imitated.

Popular themes

First woman on the floorboards

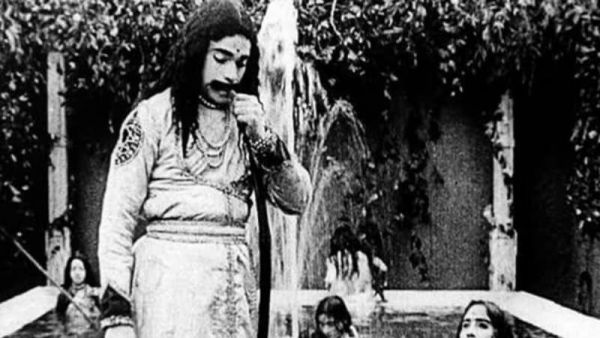

A confluence of various theatrical streams of English and Indian dramatic styles, Parsi theatre incorporated various musical scores drawn from Western, Indian and Arabic musical heritages. It used varied ragas of Indian classical music along with a variety of songs and dances. With impressive stage décor and newer techniques, it blended the best from different sources and entertained with some of the best dramas. Standing as a grand spectacle among these, is Indrasabha, which reportedly featured a woman acting on stage for the first time. It was an adaptation of Sayed Aga Hasan Amanat’s play written in 1853 for Nawab Wajid Ali Shah’s Lucknow court. However, owing to protests from conservative sections of the community, the play did not succeed. It did however pave the way for women to enter the realm of drama, a few years later.

Secularism takes centre-stage

Unique elements

Commercial Parsi theatrical productions had a number of unique and interesting elements. Three actors would chant a prayer before the drama began, after which one actor would deliver the prologue. In marked similarity to the Bengali indigenous dramatic production, Jatra, music played a significant part in Parsi theatre. The end of a play would see an actor come forward to offer a vote of thanks, ending with a farewell song. Parsi theatre was also rooted in community identity, with community members sharing a sense of oneness with the theatrical productions, and fostering identity and community culture. Communicating in the local languages like Gujarati, Hindi and Urdu, it used European-style proscenium with richly painted backdrop curtains and trick stage effects. It also depended on spectacle and melodrama to appeal to its audiences. It ushered in the conventions and techniques of realism, as it marked the transition from stylised open-air presentations to a new urban drama.

Novel dramatic devices

Leading lights

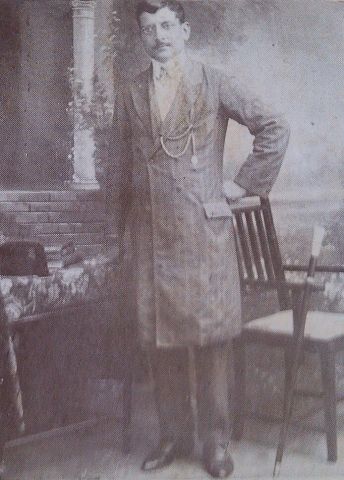

The heady early days saw the rise of many greats. Nusserwanjee Eduljee was the top comedian of the day, while Kabraji Boman Nawroji was another pioneer of the theatre who produced and directed several adaptions of classical plays from English. Maneckjee and Khori Eduljee were among the key promoters of Parsi theatre in India. Prominent among the later playwrights of Parsi theatre are Adi Marzban, Pheroze Antia, Dorab Mehta, and Homi Tavadia. These authors were well-educated, conversant with Western arts and culture, versatile and possessed of a natural sense of humour. They were also known to be strict disciplinarians, accepting nothing short of perfection from their cast and crew. The towering figure of Adi Marzban (1914-1987), considered perhaps the most gifted and prolific Parsi theatre person of the 20th century, continues to dominate. Credited with approximately 100 Parsi Gujarati plays and author of close to 5,000 radio scripts, it was Marzban’s play Piroja Bhavan (1954) that had ushered in the birth of modern Parsi theatre, as it shifted the focus of Parsi theatre from historical dramas to farces and comedies. Known for his wide-ranging knowledge on topics as diverse as literature, art and music, astrology, magic and more, he remains unmatched in his brilliance and achievements. His efforts in modernising Parsi theatre were rewarded with the Padma Shri, the fourth highest civilian award of India in 1964, and Sangeet Natak Akademi Award in 1970. Making his debut as theatre director at the turn of the 1950s, Marzban staged plays such as Sacred Flame, Time and the Conways, Hawk Island, The Curious Savage and The Little Hut in English and Fasela Ferozeshah and Hasta Gher Vasta in Gujarati. A trained musician, painter, ventriloquist and known for his comic timing, his plays were also socially relevant and well-crafted owing to his experience in journalism. He is known to have trained many young actor-directors like Pheroze Antia, Homi Tawadia, Burjor Patel and Ruby Patel who continued the Parsi theatre tradition. Another great, playwright Dorab Mehta wrote 300 plays and authored the award-winning weekly column Jamaas ni Jiloo in Jam-e-Jamshed for a whopping 54 years. The Parsi wing of the Indian National Theatre, comprising Parsi and Gujarati actors and directors, had also produced several memorable plays like Tirangi Tehmul and Taru Maru Bakalyu. Some of the key actors remembered for their contribution include Sam Kerawalla, Scheherazade and Rohinton Mody, Dolly and Bomi Dotiwala and the Kings of Comedy - Dinshaw Daji, Dadi Sarkari, and Jangoo. Dinyar Contractor, the famous multi-talented personality, Shammi, Boman Irani and Kurush Deboo, are among the other well-known artistes who have made their mark in more recent times.

Impact on cinema

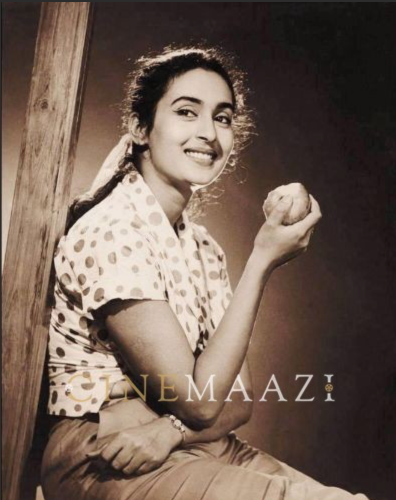

Besides ushering in the development of bhasha theatre in regional languages, Parsi theatre also led to the development of Hindi cinema. Early Parsi playwrights took to writing the scripts of Hindi films, even as the effects of Parsi theatre continue to be seen in the ‘masala’ genre of Hindi cinema. The modern Indian film industry with its sub-plots, ‘dialogues’, song-and-dance sequences and fate-driven plots are a result of the influence of the playwrights of Parsi theatre. Parsi theatre portrayed tales that were largely light-hearted and entertaining even as they delivered a social message. Hindi films with their larger-than-life depictions, extraordinary stories, and song-and-dance sequences were emphatically impacted by Parsi theatre. Plays like Raja Harishchandra which ran for over 4,000 shows, Shirin Farhad and Arabian Nights which had been staged on a massive scale went on to make the transition to 35mm. Raja Harishchandra, India’s first full-length silent feature, is said to have been an adaptation of its theatrical production, which itself was a landmark production by Kaikushroo Kabraji. When Madan Theatres produced the play Indrasabha as a talkie film in 1932, it is said to have included 69 songs already familiar from the stage productions. The film was a synthesis of Parsi theatrical strategies and European opera aesthetics. Kohinoor Film Company also produced a silent version of this film – Sabz Pari in eight reels, featuring Miss Zubeida and Sultana. The film had four daily shows at Bombay’s Imperial Cinema, with extra shows on the weekend.

Not only in terms of form and content, but the economic infrastructure set up by Parsi merchants also played a key role in early Indian cinema. Major companies like Madan Theatres, Imperial Film Company, Minerva Movietone and Wadia Movietone were founded through financial investments by Parsi merchants, who alse financed the theatre troupes.

The advent of sound in cinema had brought the theatrical idiom to early Indian talkies, as ‘filmized plays’ came to be produced by most of the studios. Some actors of Parsi theatre also transitioned to films when sound recording techniques enabled filmmakers to produce talkies or speaking films. The usage of Urdu in Parsi theatre was carried forward into film, becoming, by default, the language of cinema as well. Parsi theatre successfully defined an Indian style of expression which led to film adapting its theatre styles. With the invention of sound in motion picture, Parsi theatre lost its top position. However, its elements continued to remain an important part of the subcontinent’s cultural heritage on account of its significance and influence in Hindi cinema.

Decline in popularity

Renowned artist M F Husain had famously said that there was nothing more joyous than Parsi theatre in Bombay. However, in a far cry from its heydays to the 1990s, Parsi theatre has been plagued by uninteresting plots and tired themes. Current Parsi theatre is a faint shadow of the phenomenon it was in its golden period. The social life of Parsis growing up between the 1950s and 1980s was marked by weekly visits to the theatre, to watch, re-watch and enjoy Parsi plays. Directors such as Adi Marzban and Pheroze Antia penned original comedies about ordinary Parsis. These plays were brought to life by actors in traditional saris and topis, or smart Western suits. With some at nearly six hours-long, they nevertheless were met by cries for encores by a delighted, laughing audience. That vibrant culture is a thing of the past. Diminishing interest in the Gujarati language among Parsi youth, lack of new quality writers who are unable to match the skill of earlier Parsi-Gujarati dramatists, and a dearth of sufficiently talented actors like Jimmy Pocha, who elicited unending whistles and whoops on making their entry on stage, have taken a serious toll. Plays generally run only on Parsi festival days. Interestingly, in 1981, Mumbai-based theatre director Nadira Babbar revived the Parsi theatre style with her theatre group Ekjute’s production of Yahudi Ki Ladki (The Jew's Daughter), considered a classic in Parsi-Urdu theatre. This historical Urdu play by Agha Hashar Kashmiri, on the theme of persecution of Jews by the Romans, was first published in 1913. For 100 years, from 1850-1950, Parsi theatre had dominated the Indian culture scene. During its most creative period from 1870-1890, it had brought about a sea change in the attitude and perception about theatre. Parsi theatre will always be hailed for marking the beginning of a new tradition in Indian theatrical culture, which continues to endure albeit in a different form.

References:

Theatre in India - Girish Karnad (Daedalus)

Parsi theatre and its dramatic techniques – Dr Satish Kumar Prajapati (Pune Research World)

The Parsi Theatre: Its Origins and Development - Somnath Gupta (Seagull Books)

Laughter in the House: 20th Century Parsi Theatre - Meher Marfatia (49/50 Books)

The Legends of Indian Cinema: Series Editor - Aruna Vasudev, Sohrab Modi – Amit Gangar (Wisdom Tree)

.jpg)