An overview of Indian Cinematography

Cinema originated in the last decade of the 19th century as an interesting experiment associated with the phenomenon called persistence of vision. With rapid advances in science and technology in Europe and America, this experiment soon evolved into a fascinating medium of art. Developing essentially as a visual medium, the pictorial aesthetics of early cinema evolved from the trends in the European visual arts. Elements of composition, lighting and pictorial perspective were contributed essentially by the Renaissance tradition of painting. Visual experiments conducted by the expressionists in still photography and painting were also reflected in the films of the silent Era, particularly those produced in Europe.

Cinema came to India a few years after it emerged as a form of entertainment in Europe. People would go to the theatre and pay to watch a film. Though the early Indian filmmakers chose the stories from Indian mythology, history and folklore, the narrative technique and the visual approach followed was along the lines that was being practised in Europe and the USA. The practice by and large continues even today.

The aesthetics of motion picture photography all over the world has been influenced by the developments in technology. India is no exception. Till the late 19th century the traditional Indian painting was the miniature. As a form of painting, the Indian miniature employs a flat, even lighting and a perspective which is not strictly realistic. European cinematographers, with their roots in the visual sensibility created by painters like Vernier, Goya and Rembrandt, attempted to create images employing directional highlights and shadows.

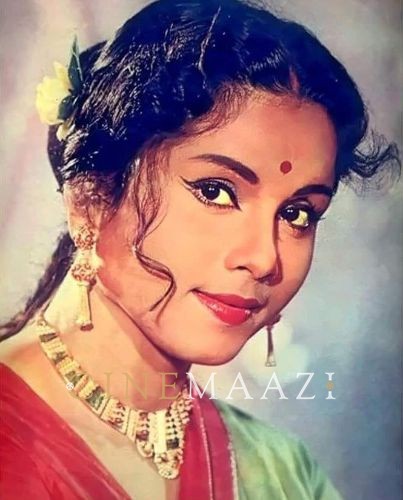

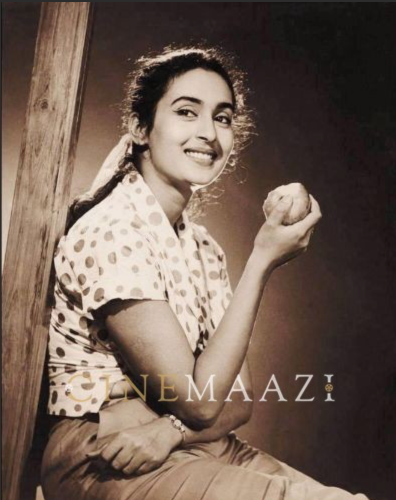

Development of still photography brought images shot in natural light, images that looked 'real'. Cinematographers also tried to impart this feeling of the 'real' to their images. The lighting played a very significant role in the process, but this was not easily achieved. It took years, when the film negative improved in speed and grain, that the film image achieved a 'naturally lit' quality. But before that an interesting development took place, particularly in the USA. The slow speed of the film necessitated the use of very bright lamps with `fresnal' lenses casting deep shadows. The varied sensitivity of the black and white film necessitated the use of a specific kind of make-up on the actors. The combination of strong bright light sources and heavy make-up resulted in images with very harsh textures. The optical experts then came up with a simple glass accessory called the 'diffuser'. Placed in front of the lense it literally diffused the light entering the camera, rendering the image 'soft', depending upon the degree of diffusion employed. While it softened the harshness of the make-up and the sharp shadow lines, it also imparted to the image a texture which was perceived as not only pleasant but also very glamorous.

In Hollywood emerged a style of lighting that employed strong back-lighting which, in combination with 'diffusers', created a school of glamour photography which inspired cinematographers all over the world.

This style of photography was very popular among Indian cinematographers till the mid-fifties. In fact, even today, the style persists with certain modifications. Some outstanding examples in black-and-white cinematography of the Fifties and the Sixties can be found in the works of veteran Indian cinematographers like Fardun Irani, Fali Mistry, Jal Mistry, Radhu Karmarkar, V K Murthy, R. D. Mathur, V. Avadhoot, V N Reddy, V. Ratra, Nariman Irani and G. Singh.

The revolutionary changes in the visual sensibility of cinematographers came with the Second World War. News cameramen brought the war to the cinema screen in its stark rawness. All the rules of pictorial composition and lighting were forgotten, to capture the reality of war as it unfolded in front of the camera at that particular moment. Western film-makers, who were either the direct witness to the war and/or its aftermath, in trying to capture the ethos of the times, sought stark images with some kind of urgency and rawness. The cinematographers rose to meet that challenge and were greatly assisted by the improved film stock and camera equipment.

Films like The Bicycle Thief, which heralded the emergence of the Neo-realist cinema in Europe, deeply influenced the cinematic and visual style of filmmakers and cinematographers in India, too. Two cinematographers who emerged during the late Fifties and Sixties, and whose work represented the post-World War II aesthetics of the cinematic image in India, were V. K. Murthy in Bombay and Subroto Mitra in Bengal.

V.K. Murthy was trained at S.J. Polytechnic, Bangalore, and later worked as assistant to the cinematographers Fali Mistry and Jal Mistry, who were creatively the most exciting representatives of Hollywood cinematography of the Fifties. Murthy's association with director Guru Dutt, who himself was seeking fresh avenues of cinematic expression, evolved a style which combined stark naturalistic lighting with innovative camera movements. The best examples of his cinematography are the films Pyaasa (1957), Kaagaz Ke Phool (1959) and Sahib, Bibi Aur Ghulam (1962). Shot in B&W (the last mentioned in cinemascope) these three films stand as landmarks in the evolution of the B&W cinematic image in Indian cinema.

Murthy's images are characterised by extremely precise framing and fine control over contrast and texture in lighting. In Kaaghaz Ke Phool he innovated and created lyrical transitions during the scenes through lightly stylised lighting and camera movement. The protagonist of Kaaghaz Ke Phool was a film director and several scenes were shot in the film studios and on sets. Murthy's splendid B&W photography captured the ethos of the Indian film industry of the late Fifties and Sixties in a manner that has never been equalled in any other film. In his photography he has achieved a healthy and invigorating improvisation over the classical approach to the film image. He has influenced a whole generation of cinematographers in India. Having assisted him for many years, I can say that he is truly the Guru of the new film image in the Indian Cinema.

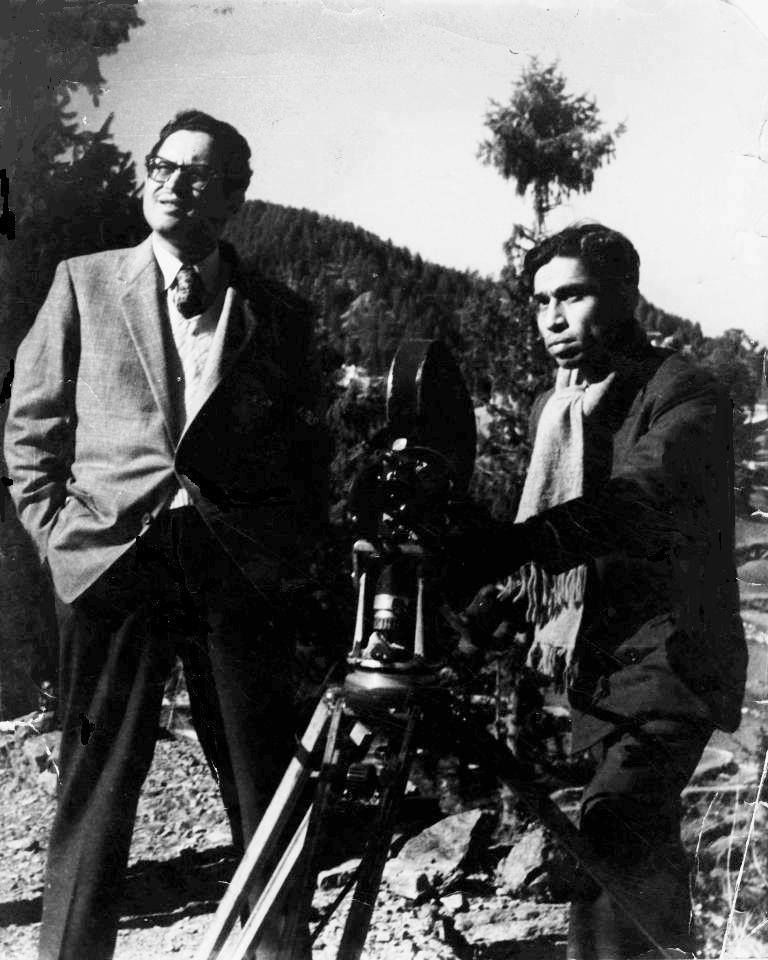

Subroto Mitra commenced his career as a cinematographer with Satyajit Ray. Ray was very much aware of the contemporary world cinema through his association with the film society movement and through literature on cinema. Ray's cinematic approach was radically different from the one prevalent in the popular cinema of Bengal. Being a visualizer himself, Ray came to film-making with an evolved visual sensibility. Together, Ray and Mitra revolutionized Indian cinematography. Though Ray was very influenced by Hollywood narrative techniques, in his work he evolved a narrative mode which was nearer to the Neo-realist school of European cinema than Hollywood. Subroto's black-and-white photography was a very significant element in Ray's films. Films like Pather Panchali (1955), Aparajito (1956), Apur Sansar (1959) and Charulata (1964) had some of the most memorable images of the realist school.

Subroto's work is characterised by meticulously executed naturalistic lighting, sensitive compositions and highly elegant camera movement. His work has inspired cinematographers even in Europe.

During my visit to New York in 1980-81, when a large exposition of Indian cinema was organised by the Museum of Modern Art, New York, I had the pleasure of meeting the eminent cinematographer Nestor Almendros. He told me that while he was studying cinematography at the film school in Paris, he saw Charulata and was totally mesmerized by the quality of images of that film. He was absolutely fascinated by the lighting that Subroto Mitra employed. He said he made great efforts and found out from his interviews how Mitra achieved that kind of lighting. He then employed the same technique to shoot some of his own exercise films at the film school. He recalled how his fellow students and even some of his teachers thought he was indulging in a very "peculiar exercise" until, of course, they saw the results. "All my work after that has evolved around the original inspiration that I got after seeing the photography of Charulata," he said, with a tremendous sense of admiration and respect for Subroto Mitra.

The Sixties saw two important developments. One, there was a big surge in the film society movement in the country. Two, the Film and Television Institute of India was established at Pune. The film societies brought films from Europe and other parts of the world which were not usually seen in India. These films made us aware of the many different approaches to lighting, composition and camera movement, other than those we used to see in Hollywood films. The experience was extremely enlightening and stimulating. Combined with the new portable camera, Arriflex, and the Nagra tape recorder, a whole new visual sensibility was evolving all over the world. Young Indian cinematographers, particularly those trained at the Film & Television Institute of India, brought a fresh approach to the images.

The early work of many of these young cameramen from the Institute was characterised by the use of reflected or diffused even light. The essential inspiration of this 'look' came from the films of Raul Coutard, who photo-graphed several films of Godard, and the films made in Czechoslovakia. For a few years, this look dominated the work of not only the graduates of the FTII, but also several cinematographers of the popular cinema. But, in a very short period, these evenly soft-lit images tended to become monotonous the main reason for it was the lack of innovation and experience of the cameramen.

The mid-70s onwards, there was a sudden spurt in advertising films on television and cinema in the West. The major requirement of advertising films was the sense of glitz and the glamour and the unconventional camera movements. In short a tremendous excitement in the images. The earlier advertising images drew their inspiration from the work of feature film camera-men. The trend reversed in the late Seventies and Eighties. Advertising images provided inspiration to young film directors and cameramen many of whom had their direct or indirect association with the advertising world. In India, too, young cameramen contributed very significantly to very creative and exciting camerawork in advertising films. Having photographed scores of ad-films and documentaries, I have had the privilege of watching the work of several cameramen. Outstanding among them are R.M. Rao, Barun Mukherjee, Chang, Vikash Sivaraman, Kiran Dev Hans, Mahesh Are and Rajiv Menon.

The cinematography of one film that influenced and inspired the work of many young Indian cameramen during the seventies was The Godfather, directed by Francis Ford Coppola. The soft, top lighting that he employed in this film, cinematographer Gordon Willies broke some of the cardinal rules of traditional motion picture lighting and created a visual 'feel' which was unique in the history of cinematography.

In India, cinematographers like P C Sriram and Santosh Sivan extensively employed elements of this style in their work and created some spectacular images. Nayakan (1987), photographed by P.C. Sriram, and Roja (1992), by Santosh Sivan, are the milestones of contemporary Indian cinematography.

The only other European cameraman who seems to have stimulated the imagination of young Indian cinematographers is Sven Nykvist, whose photography of Ingmar Bergman's films is indeed a great source of inspiration to cinematographers all over the world.

The cinematographer functions essentially as an eye of the director. It is very essential that the director of the film not only have a very clear and defined visual sense and style, he should constantly challenge and inspire the cinematographer to achieve the visual integrity of the film. It is also very important that the director and cameraman be willing to experiment and venture out into unexplored visual spaces. World cinema is replete with examples of exciting creative collaborations between the director and cinematographer. Eisenstein-Edward Tisse, Orson Welles-Greg Tollen, Bergman-Nykvist, Coppola-Willies, Godard-Coutard are a few important ones.

In India we have had Guru Dutt-V.K.Murthy, Bimal Roy-Dilip Bose, Raj Kapoor-Radhu Karmarkar, Satyajit Ray-Subroto Mitra, Mrinal Sen -K.K. Mahajan, Shyam Benegal and myself (Govind Nihalani) and Vinod Chopra-Binod Pradhan.

Shyam Benegal is one of those directors a cinematographer dreams about. Extremely aware, and articulate about the various movements in visual culture, both in the West and the Orient, Benegal thinks in terms of a very well defined visual personality for each of his films. I had the privilege of photographing twelve of his feature films and several of his documentaries. Our endeavour was to create a very distinct and unique visual articulation for each film. It was from such an association that I could create the images of films like Ankur (1974), Nishant (1975), Bhumika (1977), Kalyug (1981), Kondura (1977) and Junoon (1978). Bhumika, for instance, dealt with three periods of Indian cinema including the Silent Era. We went to the National Film Archive in Pune to study the lighting style of the Silent Films and the films of the Forties and Fifties. We achieved a distinct feel for each period by employing film negatives of different contrast and tonal qualities.

The current mainstream Indian cinema is dominated by the visual style which might be described as highly glamorized or stylized realism. Since the early Eighties, a new generation of cinematographers has created a new awareness about the contribution of the cinematographer to the experience of the film. Some of the eminent cinematographers reflecting this new visual sensibility are Santosh Sivan, P.C. Sriram, Ashok Mehta, Binod Pradhan, Madhu Ambat, Rajiv Menon, U.B. Rao, Baba Azmi, Francis Xavier and others.

Along with the popular genre there is what has come to be described as the Parallel Cinema in India. This is a serious kind of cinema with emphasis on experimentation, both in the form and the content of the films. The strength of this kind of cinema lies in its struggle to resist the compulsionist pressures of the popular genre. Unlike the popular cinema, these films attempt different narrative modes demanding an equally varied visual response from the cinematographers. From the stark to the most sensual images have been achieved by cameramen like K. K. Mahajan, A. K. Bir, Venu, Kumar, Shahji Karun, Jehangir Chowdhury, Virendra Saini, Piyush Shah and Anup Jotwani.

With technology becoming more and more refined, the Indian cinematographer faces the challenge of realizing to the full the new potential of this medium to create the magic and poetry of the cinematic image.

This article was originally published in Indian cinema 1994. The images used in the feature are taken from the original article, cinemaazi archive and the internet.

Tags

About the Author

.jpg)