Hidden Gems of Indian Cinema: Aafat

While cops and robbers both have been the mainstay of numerous popular Hindi films, a sustained view into their worlds that would form a better part of a film’s narrative has been rare. The procedural drama has never really enjoyed a sub-genre like status as it does in Hollywood or other cinema — be it European, Japanese or Korean — despite the detective genre enjoying mainstream interest routinely from the 1950s with Apradhi Kaun? (1957), Gumnaam (1965), Intaqam (1969) in the 1960s and Manorama Six Feet Under (2007) or Detective Byomkesh Bakshy! (2015) in the recent past. One could argue that Ab Tak Chappan comes close to being one of the best procedural films made in mainstream Hindi cinema but it remains more invested in the soul of the lead character as opposed to the procedural talents that he possesses. But, while police and law dramas still have some degree of procedure thrown in for good measure, crime rarely gets any attention beyond the perfunctory and it’s in this light that discovering Aafat (1977), a barely recalled 1970s’ urban crime thriller, becomes a thing of joy.

Following the growing smuggling and drug-related crimes in Bombay, Din Dayal (Nazir Husain), an influential and respected businessman, uses his sway in Delhi to get a special CBI officer Inspector Amar (Navin Nishcol) on the case. Din Dayal’s nephew, the sole heir to the family’s fortunes has become an addict and he personally requests Amar to nab those who are hell-bent on ruining the youth of the country. Amar gets the lead of a newspaper’s editor Balraj (Sajjan) from Jagpal but before he can reveal more information, an assassin — hired by the secret gang of Shera (Amjad Khan) — kills him. Amar lands up at the newspaper and meets Mahesh (Mehmood), the paper’s crime reporter and his childhood friend. Although Balraj is keen to share the details of the gang’s modus operandi, he backs out the moment he gets a threatening call from Jenny (Faryal), the gang’s resident moll.

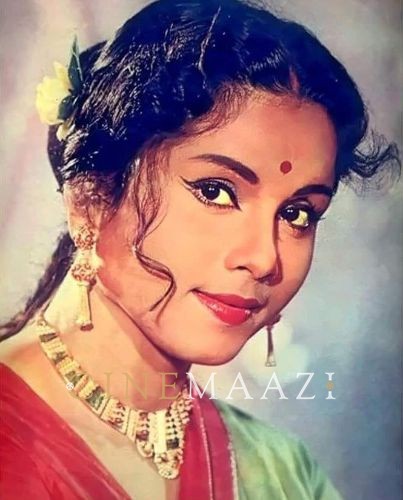

Amar decides to come back later in the night to investigate Balraj’s office but finds him dead and bumps into a mysterious woman (Leena Chandavarkar), who overpowers him and runs off with the evidence that Amar was looking for. Later, Amar finds out that the mystery woman is in fact a cop named Inspector Chhaya and she is also investigating the same gang. Mahesh and Amar track Rajni (Jayshree T), the courier for the gang who is given drugs in exchange for her work and who also turns out to be Chhaya’s younger sister. Amar doubts the commissioner Hardayal (Kamal Kapoor) to be in cahoots with Jenny, Shera, and the ilk. Along with Mahesh and Chhaya, he too inches closer to unraveling the mystery.

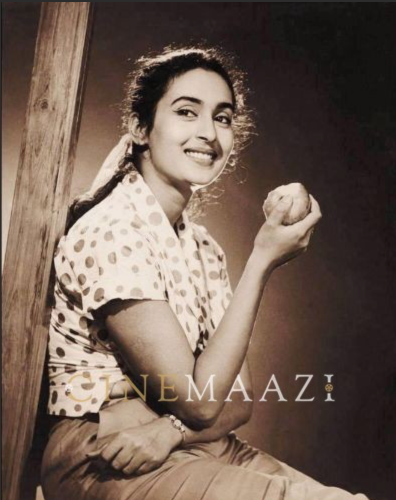

Things promise to fall into place when Amar finally meets Champa (Prema Narayan), a street dancer employed by the gang of smugglers, and she gives him vital information about a consignment due in few days. But seeing a hung-over Champa leave Amar’s hotel room in the wee hours of the morning, Chhaya imagines the worst and decides to go her separate way to solve the case. After numerous crests and troughs, the mystery gets solved and so does the confusion between Chhaya and Amar.

Directed by Atma Ram, Guru Dutt’s younger brother, the film’s wafer-thin veneer of modernity is just perfect and Ram’s credentials as a documentary as well as ad filmmaker seem to come in handy. Aafat might pale in comparison to Shikar (1969), Atma’s Ram’s most recognized work, which incidentally was a well-crafted procedural drama too, but this one deserves to be unearthed along with his Aarop (1974), a drama about corruption in journalism.

This is a reproduction of the original published on Firstpost.com on December 2, 2017. https://www.firstpost.com/entertainment/atma-rams-aafat-navin-nishcol-leena-chandavarkar-starrer-is-a-well-crafted-procedural-drama-4238423.html

Tags

About the Author

Gautam Chintamani is a film historian and the author of Rajneeti (Penguin-Random House, 2019), the first biography of Rajnath Singh. He is the author of the bestselling Dark Star: The Loneliness of Being Rajesh Khanna (HarperCollins,

2014), The Film That Revived Hindi Cinema (HarperCollins, 2016) and Pink- The Inside Story (HarperCollins, 2017).

.jpg)